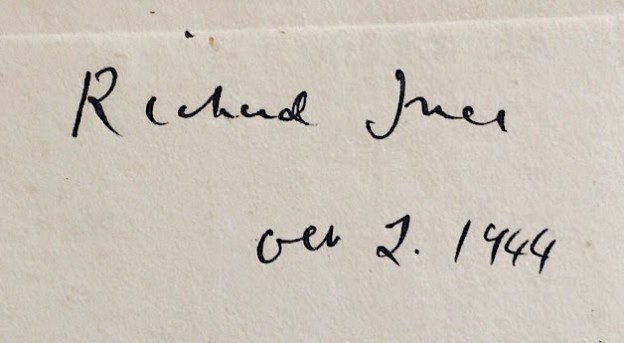

The final part of Richard Ince's Talking Beast. A candid inquiry into the nature of homo vulgaris. (London: W. Hodge & Co., 1944.) It is a heartfelt and still interesting polemic from the 1940s. Ince acknowledges as his inspiration (and mentor) Archibald Weir, the Buddha of Marley Common:

"...it might be supposed that I am a disciple of Archibald Weir.. I am a disciple of no one, preferring to seek truth wherever I discern it. In the East they have a saying: "Where there is no Buddha hurry on, and where there is a Buddha, do not linger." The paradox would certainly have been approved by Weir, who wrote: "I do not seek to formulate tenets or to make disciples. The intent of these books would be frustrated entirely if any such success were obtained among their readers. All that I can wish to offer is assistance to earnest minds in the effort to think for themselves...'

Having found a signed and jacketed copy (at a sadly low price) we can reprint the blurb from the inside flap and also a press-cutting pasted to the rear endpaper. This review from The Field leads one to think this may have been Ince's own copy and the book was reviewed by this horsey magazine because it was about an animal...

Inside d/w flap reads:

Our present world is not, for many, a pleasant place in which to live. The conditions force even the least thoughtful to consider why they are here. People ask: Has western civilisation failed? Has Christianity failed? Is there hope in the Churches? In religion? And, if so, of what kind? Only a fool or a knave could be satisfied with things as they are. Only a fool or a knave could imagine that outbreaks of hatred and the competitive spirit could bring peace or satisfaction. This book by an author who has thought deeply and experienced deeply looks without prejudice or ready-made opinion on the content of our consciousness as it exists today. He has attained a philosophy which brings order out of chaos and a measure of peace out of strife and muddle.

If you are not satisfied with the world as it appears to you and believe there are better possibilities for every one, you should read TALKING BEAST. It will help you to face bedrock facts, no matter how ugly, with courage and cheerfulness.

The press-cutting reads:

International Press-Cutting Bureau - London. THE FIELD.

11 November 1944.

This is a book, as arresting as its title, which is better read twice than once. It will produce both acceptance and antagonism, according to the reader's mental progress from talking beast to mature human. It is neither a religious nor a psychological book, but an unprejudiced expression of the fundamentals of true living, of human contacts, of business relationships, of the reasons and uses of the muddle talking beast has made on the world. Richard Ince does not look upon Christianity as a religion (organised), but as the enlightened personal way of life. He reasons that no mere religion is ever final, no Government the attainment of perfection, no science the last word and no death the end of life. Development wing the essence of creation, man's fullest living lies in adapting his being to the still small guiding voice, in the wisdom of "accepting the shoves and pokes of Destiny cheerfully and graciously". Talking beast walks in ignorance, thinking he knows, forever grabbing, and with no sense of values; yet there is always the gleam of light available, giving the wise judgement and the serenity that liberation from the material clatter of modern existence gives. Richard Ince unties many knots in the tangle in which we find humanity.

CHAPTER VII

THE BOUNDARIES OF NECESSITY AND THE MARCHES OF FREEDOM

The English-speaking peoples have always been much concerned with the idea of freedom. They have been everywhere leaders in the struggle against aggression and, the tyranny of the few over the many. Not being a logically-minded folk, but more easily moved to loyalties of the heart than of the head, their history has been subject to strange turns and unexpected developments. They have been devotedly loyal to the idea of kingship but they have never yielded to the illusion that kings or emperors or dictators are intrinsically superior to themselves. They are jealous of their own divine right to grumble and criticize, they greatly prefer the romantic fiction of kingship to its stern reality. They delight in appointing a strong ruler and then whittling away his powers until it becomes difficult to decide who is ruler and who is ruled.

Freedom in the popular regard is an extremely loose conception. Broadly defined it would seem to indicate the right of each individual to manage his life entirely in his own way. Such a conception is but the vaguest of abstractions, and on analysis is found to hold only a negative value. It is the attitude of the man who sturdily announces: "I will tolerate no interference."

On examination it becomes apparent that the life of. the Miller of Dee was far from satisfactory. Even when regarded from the lower levels, the legend of the jolly miller, though it gave birth to a good song, was certainly rooted in the sterile ground of egoism.

Freedom has ever been the noblest of war cries. But in the quiet and reflective times of peace honest inquiries into its nature gives occasion for many doubts. Much that passes for freedom in the debased currency of human speech is found on examination to be no more than the licence claimed by ego. Ego is ever on the alert to assert its "rights" and to dominate others, while priding itself on its altruistic zeal. This lack of discernment in talking beast's perception breeds much mischief. Thus it often happens that. he who shouts loudest in praise of freedom is most dominated and enslaved by ego. This truth is vividly illustrated in the private lives of many politicians. The most forceful social democrat is often found in his home life to be no better than a domestic dictator. In public he is known for his lofty flights of rhetoric, declaiming that all must enjoy equality; at home he is quite content to have a slave in the kitchen and is furious if his wife expresses an opinion contrary to his own. Human frailty wriggles away from the contemplation of such hypocricy; repeating the popular saying: No man is a hero to his valet. It would be truer to say that to the beast no man can be a hero.

Adult man has, great difficulty in realizing that the core of freedom lies in Self and not in ego. Ego is continually beating unavailingly against the hard framework of circumstance, and the more fiercely it beats the more severely does it punish itself. We are all born into a condition of almost complete slavery. We find ourselves in a world of space, and time with a number of needs that must be satisfied by others, and our early attitude is one of lusty rebellion. The first sound we emit is a cry of protest. Later, the hostility expressed in that first infantile bellowing will be shaped into words. Remembering the texture of spate-time life we have always to be on our guard. No matter how great be our academic attainment, much of what we write and teach may be no more free of egoistic rebellion than was the infant's cry. But because we use learned and impressive words, the origin of our message is not so apparent. Still enslaved to the egoistic forces, we grow to adult life. Some few go further, relax their hold on ego, attain to maturity and pass through the devastating experience of a second birth. But for the majority adult existence is the rule. They talk, they struggle, they respond to the pull of immediate pleasure, they live in the dream of a dream which they mistake for reality. Not until they are approaching the higher condition of maturity do they begin to ponder on the problem of whether they are free agents or the playthings of necessity.

To get a better understanding of the problem it is necessary to look far ahead and see man as the finished being he is destined to become. So long as he is controlled only by ego and personality there would appear to be no hope for the maturing process. For the adult there can be nothing but toil, struggle and the unease of restless life leading to dissolution. If in the pages of history we could see nothing but the meaningless contention 4 egos and personalities, the scene would be illuminated by no ray of hope. History, considered from this angle, can provide nothing but counsel of despair. No philosophy could be based upon it, no cheer for suffering men; no lessons in the art of living. Happily there is no page of history, no matter how dark the age under review, which does not show the influence of Self infiltrating here and there to oppose or mitigate the savagery of ego and to introduce humanitarian inspiration. in our civilization, consciousness and the thought process are far from being generally understood. To adult man the conception of a thought-atmosphere, akin to the physical atmosphere we breathe, must appear remote and unconvincing. His experience of such an atmosphere is too fragmentary and too elementary to bring true understanding. As he advances, however, from the adult to the mature condition of being he becomes far more sensitive to the atmosphere of thought in which we all live,' he begins to realize that we are not isolated units occupied with a mental process called thinking, which goes on in the grey matter underneath our skulls, but that we are all linked up by the vast ocean of the unconscious processes, racial and personal, which feed consciousness: an ocean out of which spring those clear sequences of pictures we call "thinking." The physical ocean, with its unfathomable depths, is everywhere the symbol of this unconscious. It is met with in inspired scriptures; it is met with in psychology and dreams. The description here given of the process referred to is as close and accurate as is possible in using the crude instrument of human speech.

To imagine, as many of our forefathers did, that the humanitarian stream of thought came into the world either by chance or by man's conscious striving, would be to misunderstand the purpose of Self in our space-time consciousness. Figuratively speaking, ego is lord of the region of bondage and Self of the marches of freedom. It is always and everywhere the lightening of the burden of ego which increases freedom, even in the sphere where the hard framework of necessity, material, social and psychical is most in control. We see the beginnings of the higher leading of Self in the insistence of codes of manners and morals by even the most primitive civilization. The manners and morals imposed may be far from ideal, may even be cruel, ignorant and superstitious, but they at least amount to a slight gesture of humble acknowledgment of a higher power whose aim is far different from the egoistic struggle to survive. In these slight, elementary movements the still small voice of Self begins to be heard. In Sir James Fraser's Golden Bough we read of the many customs, religions, magical and ethical which are the infants designed to grow into orthodox science and institutional religion. A great deal must not be expected of these efforts even when they have grown into accredited science and respectable religion for they are held back by the herd instinct and the herd instinct prefers comfortable time-honoured inertia to the dangerous pioneering prompted by Self.

Talking beast in the adult condition is necessarily puzzled by the controversy as to whether human beings live under a system of free will or are under the complete control of fate. He is under the misapprehension that study and hard thinking can settle the problem. He does not realize that his consciousness is no more static than is any other living process and is limited and controlled according to the zone he has attained. No academic training will enable him to understand the problem; he must wait patiently until consciousness itself changes, deepens and widens. He must get rid of the herd-beleif that there is only one kind of consciousness for mankind and that the only food consciousness requires is to be found in schools, books and universities. In other words, the problem is not a problem of thinking but a problem of being. The more tightly he is bound by the fetters of the ego, the more closely will his freedom of thought, understanding and action be confined in the prison-house of space and time. The more he identifies his life with the promptings and aspirations of Self the wider will his sphere of freedom become. But life, as we experience it on this planet, is strictly limited and confined. We are never masters of time or of space in anything but a crude journalistic sense. Though we have "mastered the air" we are still killed stone dead if we fall a few hundred feet out of a plane. The bird is in far better case, for his mastery of the air is so complete that he is never killed by a fall.

How then can it be asserted with any truth that man is master of his fate? We move here among thoughts that' are difficult and hard to reconcile one with another. The human animal must exercise patience. He must humbly admit that despite all his outward attainments he is still unfinished. The sparrow, in its order, is a more finished creation than he. He must be content to wait upon those influences which will assist him to reach a greater degree of maturity.

At this point my reader will probably become suspicious. He will look for some hidden motive. He may even' suspect that I am the emissary of some new religion or the secret agent of some society aimed at the framing of a new ideology. I must ask him therefore to take my word for it that I am not a Jesuit nor an impresario of the Cambridge Group; neither am I a High Anglican nor a Low Buddhist. I am simply a talking beast who wants to know and understand, and as a result of this keen desire or aspiration, certain small but deeply significant experiences have come to me which I would fain share, so far as such experiences can be shared with others. Talking beast naturally does not wish to join any religion or movement that is likely to make serious demands upon his time or interfere with his sturdy independence. For this reason he is naturally suspicious. But if it is a question of becoming a better beast, a little less beastly, more efficient and more successful in the art of living, well, he might hesitate before turning away with a shrug. But probably somewhere at the back of his mind lurks the belief that science has made the solution of dark problems easier than it used to be in pre-scientific days. And since science rests wholly on the reasoning faculty, he is led to believe that, no matter how he lives, if he only thinks clearly, good and desirable results must follow. This is an illusion which a true understanding of the function of the unconscious will correct. But the man of scientific training whose mental food is the daily press, clings desperately to the reasoning faculty of the conscious mind. It was largely owing to this tendency that a few years ago a number of intelligent people were led astray by the seemingly attractive red herring known as behaviourism. The behaviourists claimed to have made a most important scientific discovery. They had discovered that men's morals and even their highest aspirations, were due solely to the proper functioning of their glands. If you were a degenerate who had served several terms in prison, all that need be done was to send you to a gland specialist who would find out which of your glands was out of order, give you the injection indicated, and you would, after a course of treatment, be transformed scientifically from a sinner into a saint. Religionists did not like the discovery, but many scientists were delighted with it. It seemed to put the whole universe of thought and of becoming, into their hands. It opened up Wellsian dreams of the possibilities of things to come. Such a theory, silly as it was, might have done quite a lot of damage had not certain philosophers drawn attention to the fact that the behaviourists, whether good scientists or not, were very weak thinkers. They had quite cheerfully taken it for granted that space-time and matter are all separate, independent entities. They did not realize that these conceptions are creations of consciousness fashioned out of an ephemeral world, wholly transient in its nature. It is easy enough to build a house when one has been given the material. The behaviourists, unfortunately for them, had no material with which to build. They. could not create glands; they could only deal with those already in existence. And even these foundations were continually changing. In other words the behaviourists were trying to prove that man is the creation of his glands. He may be, but what is all while creating his glands? Instead of explaining a difficulty they simply pushed it further back. Behaviourism might be expected to prove attractive to the back the inert for if a simple injection can cure not only your body but your soul, how much easier and less would life become.

Behaviourism. would not be worth mentioning were it not one more signpost pointing to the stupidity of talking beast and to the fact that he is always open to infection from the many silly ideas floating about in the thought stream. Education as we have it to-day is not capable of providing immunity to any large extent. The breeding grounds of propaganda are immense. They are found wherever there are inertia, greed, hatred and peevishness. The greatest danger arises when such breeding grounds are deliberately taken over by the State to foster the primitive instincts of the beast. When fear and compulsion are applied under dictatorship the resulting social disease spreads havoc far and wide.

Social life, no less than science.is necessarily built on structure of make-believe. It is composed of grades, officers and classes. We have a king, president or dictator, and under him a more or less intricate system of public servants to whom power of one kind or another is delegated Intrinsically these different grades of rank or position have no true or permanent value because they are not based on the real qualities of the individuals concerned. They but external badges, enabling personalities and egos to discharge certain necessary functions. These personalities and egos act according to their nature, attending to their own interests first and the interests of the State afterwards. The man of to-day is, not quite awake to the true state of case and is not inclined to be honest about it. He does not realize that. he is a beast with the faculty of talking and reasoning, and therefore he has all kinds of illusions about himself and others. He either expects too much or too little from human nature. He expects the doctor to act towards him as a good samaritan and charge him little or nothing for his services; he, expects the clergyman to be the sort of saint who will listen to all his grievances with complete sympathy and will reassure him of the fact (of which he is at times: doubtful) that he is really an awfully decent fellow. He may even expect the lawyer to act as a kind of terrestrial clergyman, save him from foolish blunders and send in only occasional and very moderate bills. Or else he takes such a low estimate of human nature that his life degenerates into a daily grouse against the wickedness of the man next door and the fellow over the way. The wise man constantly remembers that rank, profession and position in society carry no weight in the kingdom of reality. They are entirely superficial and makeshift. Each individual must be considered on his own merits no matter where he be in the social scale.

The social make-believe by which we live is certainly necessary and unavoidable in space-time living. If man were suddenly given the capacity to see through I externals to the truth within, society would come toppling down in ruins. But out of the ruins a truer way of living and a more mature society might be built. The crucible of war tends, in slight degree, to have this effect.

Freedom in the political sense is too crude a conception to throw much light on the possibilities of freedom as here considered. Political freedom is mainly negative. It aims at breaking down tyranny wherever and whenever found. A fair field for all and no favour is the basic condition in view. In, cherishing this excellent ideal humans unhappily forget that they are talking beasts. Difficulties flourish like a weed as soon as the fair field has been provided. The name of the weed is ego. Governments are powerless to stamp out ego. You cannot get rid of it as you extinguish a fire by organizing an army of fire-fighters. You can only slightly and with difficulty neutralize its ravages by legislation. You cannot, by teaching children to read and write or by feeding sociology or some form of religious dogma to them, sublimate it into constructive channels. You may get rid of political tyranny by shooting the dictator and rounding up his gestapo, but the fundamental problem of the ego-pull in man's unconscious will still remain. It will remain until he has passed through the various stages maturity and attained complete manhood. Only then will he be free forever from the pull of ego and at one with the forces of destiny. To make this statement is not to belittle the vital importance of political freedom. Without it all, progress and development is doomed to wither and die, The dictator-ridden state can only run through the old vicious circle of change in which the rot within festers and breaks out in neurosis or actual physical disease. It is an attempt to embalm existing conditions in the body politic. In this way the corpse can be preserved for a long it will never be anything but a corpse and a centre of infection. There must be freedom of thought and freedom from all compulsions except such as are necessary in interests of safety, morality and the maintenance of essential services to the State. Without these Self is hampered in its efforts for a fuller life and a better fulfilment of its trusteeship towards others.

Nevertheless crude methods can only attain crude ends and for those who would get a better understanding of the boundaries of necessity and the marches of freedom it is necessary to consider more closely the cords with which ego seeks to make Self a prisoner, and the methods which Self must employ in its efforts to gain freedom in spacetime living; freedom to bring more light to them that sit in darkness and in the shadow of death.

So elusive is Self that its very existence is held in doubt or identified with ego until a fair degree of maturity is reached. No doubt some readers will imagine that I am concerned with a fiction when I write about Self. Perhaps .they would even expect an, effort to be made to convince them by argument, unconscious of the fact that argument can prove nothing. Here is a case then for waiting upon growth: denial in this connexion may be as emphatic as it will and intellectualism as triumphantly assured, but in no case can the good offices of Self be escaped. That still small voice insists at times on being heard. It is a clear, deep whisper that cannot always be drowned by the loud shouting of even the most tempestuous ego; and the effort to drown it frequently results in those forms of illness the psychologists call neurosis, and the doctors call hysteria.

The quality which renders Self so elusive is the share it has partly in the nature of time and partly in the nature of timelessness. For Self stands at the gateway between the conscious and the unconscious and can look either way. In one direction he is in contact with a world of ephemeral change, separated at many degrees from reality, and in the other direction he looks into a. world of darkness and yet a world which might not be dark were it not for the dazzling light of the space-time world which intrinsically appears to have no meaning. For the time-consciousness is certainly based on something deeper, glimpses of which have been revealed by certain experiments of the psychologists and by certain experiences of the mystics. Self existed before the time-consciousness came into being, and Self will continue to exist after the time-consciousness has been obliterated by the shattering of the physical envelope. Self in timelessness is beyond dualism, beyond the boundaries, of necessity and the marches of freedom. But in incarnation it finds itself imprisoned in the hard framework of matter and compelled to work, along with others, in conditions limited by the time-space of consciousness and by certain codes, 'conventions and moralities which the individual has evolved in the long process of his struggle to rise in the scale of being. At birth Self knows hardly any freedom at all. Its only reaction to hard circumstance is, as stated above, a cry. With the passing of years the marches of freedom are extended slightly. The method by which freedom grows is strictly personal to the individual. It depends on an ever greater mastery of the art of living wisely in space-time conditions and an increasing power to discriminate between the values of things. The feeble-minded, a category which includes almost the whole adult population, tend to stress the wrong things, and hence the music of life is spoilt by false emphasis. In this way Self is led on to the great discovery, not made until the advance stages of maturity have been attained, that Self universal, (the Atman of Hindu philosophy) is the only absolute value, all else being relative, perishing and only of symbolic significance.

In the conditions imposed by incarnation, limited by the narrow vision of tenuous, time-space consciousness, baffled by the dark surround of the unconscious from which it appears to come and to which it appears to go, Self asks a crucial question: Why am I here? Obviously its purpose is different from that of ego and personality which are only concerned with the material conditions which have produced them, and whose purpose is to survive at any cost. Self's hopes are not set on survival for it has its home in the imperishable real. It is fed always by the higher unconscious, even to its highest reaches. And it is one with the source of all wisdom. Why has Self come to endure the narrow conditions, the fever and the fret of ~ life which seems devoid of meaning and purpose? This is a searching problem which haunts the reasoning mind, seeming insoluble. Yet even the adult is not left in complete darkness. There is a ray of light, and with increase of freedom the light will grow. The beginnings of revelation come to him from his higher unconscious mind. From this quarter come certain aspirations and impulses which have no connexion with the survival urge of ego and no part with the vain assertiveness of personality. All humanitarian efforts have their origin in this sphere. The great leaders of mankind have borne witness to this fact. But there, is no need of any external revelation or dependence on historic evidence, for the most compelling evidence is found in the human being's own consciousness. If such light as he finds there is dim, it is himself he has to blame. The windows are there but the glass must be kept dean. If his windows are dirty with the black soot of ego or painted with the alluring colours of personality he must not expect a clear illumination.

Perhaps to seek to express in words that which needs to be known in experience is futile. The nearest we can get to . expressing the matter in crude language is to say that Self has incarnated to gain a particular experience and to suffer those uncomfortable encounters inevitable from trying to help others in their pilgrimage. Such offices may result in crucifixion; they may result in a draught of hemlock or they may result in a lift of petty pinpricks and vexations. But in any event Self remains serene, capable of withdrawing into itself and knowing always the deeper harmony which is its link with the creator.

When we consider the purpose of the individual life on earth, in all its detail, it is hard to interpret. It all appears haphazard and indeterminate. A centre of consciousness finds itself the child of certain parents, living in a certain country, in a certain sector of the time-process. The rational consciousness can ascertain no reason for its coming to these people at this time and place. The circumstances almost always appear hard and other than the individual would have selected if he had been consulted. Only a far deeper experience of the situation and a far keener insight than the adult possesses could throw the necessary light on this dark problem. A true understanding of living processes reveals the fact that nothing in the universe happens by chance. That it appears to do so is due to the fact that we are not acquainted with all the laws involved. If you fling a handful of sand into the air the grains will fall to the ground and form a pattern. A number of forces are at work directing what form that pattern shall take. But not the acutest human intelligence can follow all these forces so as to foretell where each grain will fall. Self's incarnation is a resultant of many forces, but these forces are acting in a region far higher than that of space-time consciousness. The individual life on earth is, figuratively speaking, like that grain of sand. It is also like a page of a romance into which a reader dips at random. He does not know what came before nor how the story will develop later. Were he in possession of this before-and-after knowledge, Self's purpose would be clearly revealed to him. Nor would he have any occasion for regret, no matter how difficult or how painful the pilgrimage might prove at times. For Self, which has taken all wisdom for its province, does not make mistakes. It has an end in view and always and everywhere it uses whatever 'means come to hand to further that end. The only regrets feeble-mindedness is justified in feeling are regrets that it did not always make the best of its opportunities. Too often it failed to react to external happenings in the way wisdom prescribed. For here the will, inspired by aspiration, can be used with vital and far-reaching effect, and here it is that the adult can, if he will, very definitely extend the marches of freedom. To meet every situation as it arises with sincere inward serenity, a serenity very different from make-believe cheerfulness, that conceals impatience beneath, is the only true and helpful reaction. Nothing short of this will satisfy the aspirations of Self. Unless there be a true serenity of spirit and the capacity to sink down into the deeps that lie beneath surface peevishness, the earthly pilgrimage becomes a vague, purposeless wandering. For no altruistic effort, no faithfulness to duty, no scrupulous observance of social or religious codes can take the place of this fundamental need for serenity and tranquillity in the inner life of the individual; a serenity and tranquillity fed and sustained not by inertia or the insensitiveness that may result from a good digestion and a vigorous constitution, but by a wisdom which has learnt to discriminate between the valuable and the valueless.

Thus it will come to be understood by those capable of seeking enlightenment that the purpose of Self in space-time is to extend the marches of freedom. The great world which forms the stuff out of which the spot-light of consciousness is fashioned and upon which it is directed, is at first utterly confusing. Everything has to be regarded, considered, practised. Talking beast does not understand himself. Others present continual surprises. And while the poor beast is puzzling over the strange and contradictory messages received by its sense perceptions, it suddenly finds itself the target for a ' barrage of helpers known as teachers, professors, schoolmasters and committees for herding talking beasts into the pens of education None of these is at all interested in the puzzled questions of the little beast. They are not sages or philosophers or inspired guides but just paid officials who receive a salary for imparting information according to schedule. It is a difficult situation for Self whose home is reality and who is in touch with cosmic or universal consciousness, from which. all wisdom comes. On the one hand are the professors who teach that William conquered England in 1066, and that when water reaches a certain degree of hotness it turns into a warm mist, and on the other hand is Self who whispers that all this is mere foolishness, waste. of time, of little value to anyone except the teachers who make a living out of it, and the politicians who fight one another as to which kind of information shall be fed to the children and how much milk shall be supplied to keep their bodies in a suitable condition for mental stuffing. Self whispers that the imperative need is to understand life: to know why the beast is here and what he is to do about it. Will the gaining of a school certificate, Self asks, help him to understand life or to become something better than he is? Will the taking of a college degree, a double first at Oxford or a treble first at Cambridge, help him in these deeper matters which alone have intrinsic value? It is perfectly true that for those in the state of consciousness known as space-time, space and time have their claims. There is a career to be considered and prepared for. Concerning this, Self cares very little, though ego and personality, including the egos and personalities of others, care a great deal. A child knows that if only he can get at the right kind of information and find a sufficiently wise guide, his pilgrimage may become deeply enlightening and purposeful and bring to him priceless treasure of the quality that endures. Stirred fitfully by Self, sometimes consciously, more often unconsciously, he reads books; he seeks out those who appear to understand more than he does; he retires into himself to muse and to consider. At certain times he seems to happen, as it were by chance, on the books or the friends that he most needs at that juncture. In times of crisis it happens that he meets the kind of people who can help him and by all these means he gains a better knowledge of, himself and of his ever-changing moods. He may even begin to understand that his freedom grows in proportion as he learns to control his moods and to pay less attention to the claims of ego. For the higher burden imposed by Self is far lighter than the burden which ego is compelled to stagger under. Self can confidently deliver the fertile message: My yoke is easy and my burden is light. For Self will encourage the beast to journey far beyond the regions of fruitless resistance and grumbling in which ego is doomed for ever to labour, like Sisyphus at his stone.

The chief factor in the struggle for greater freedom is the presence of others. In our earliest days others minister to our needs. Out of these ministrations grows too often an exaggerated sense of responsibility and a false sense of proprietorship. We are born into the world alone; we live alone, notwithstanding all deceptive appearances to the contrary, and we die alone. Such responsibility and proprietorship are therefore fundamentally illusory. Self, which is only partly of this world, is always aware of the true situation. In this connexion talking animal is at a disadvantage as compared with his untalking brothers who in their degree are more finished than himself. He too often gives his children a stone in place of bread, for reason and speech are sadly misleading as to the true values of things. The stark truth, which we are always blinking, calls us to witness that civilization rests on a basis of fear

and self-interest. We have become accustomed to herd together, not from motives of brotherly love but because we dread loneliness. Yet loneliness is the crucial fact to which we have to become reconciled. The close herding of bodies together will not banish but will rather increase that loneliness, for dislike or hatred of another drives us far from him in the realm of reality. We may linger for hours to gossip in the market place, but always and inevitably weariness supervenes and consciousness is thrown back upon itself. The sooner humankind realize the true basis on which civilization rests, the better for them. No good will result from trying to trace its origin to the ministrations of religion, the inspiration of the spirit or the march of a progress destined to lead to some ultimate millenium. Our human dwellings, whether in Park Lane or Old Kent Road, are built upon the mud and it is ego which has built them. It is well that we should cheerfully and humbly accept the facts.

Only if we bear in mind what civilization is and the forces which have brought it into being shall we be properly equipped to tackle the many problems which others present to us and which we present to others. If we are to have sincere relationships with others we must clear our minds of much cant which has become enshrined in social life. Insincerity only leads to further insincerity and the clinging to false values in the intimate relationships of life. Man in society is continually slipping into these false relationships and thereby causing himself surprise and bewilderment. He calls things by their wrong names and is Surprised, when disaster results. If you ask for a hairbrush and are supplied with a carving knife, and if, in the interests of peace-at-any-price, you co-operate in the fiction that the carving-knife is a hairbrush, daily life will not thereby be rendered easier. The illustration may appear trivial and absurd but it is no exaggeration of a condition which prevails among many nice people to-day. There is a widespread convention that parents and children are always and everywhere very near and dear to one another. Intimate acquaintance with quite a small circle of families anywhere in the world proves such a belief to be false. It is the rare exception and not the rule for parents and children to be in close and intimate sympathy. When such conditions prevail there is occasion for the deepest gratitude to destiny. Parents and children need to rise above this foolish current convention and to take a dispassionate view of the relationship between them. The adult is not likely to become a wise parent nor can children in that state be expected to deal with the intimate relationship with much wisdom. By mutual forbearance they may avoid the worst disasters. An honest attempt to' keep the relationship sincere will be of decided value. But if current sentimental conventions be mistaken for basic truth, much misunderstanding and suffering are bound to result. Humility is needed on both sides and some understanding of the origin and purpose of ego and personality. But man's innate hardness of heart usually prevents him from humbling himself to the requisite degree. He thus shuts in his own face the door to progress.

When the single life has passed from maturity to complete manhood it will have learnt that its treatment of others can only be expressed in the form of a trusteeship. By that time ego and personality will have passed entirely under the control of Self universal. The complete man will no longer be deflected from his path by the lure of personality or the urge of ego. He will not claim leadership but leadership will I be accorded- to him, for in the country of the blind the sighted man is king. Relationships according to the flesh will have little meaning for him. His trusteeship compels him to look equally on all. From others he demands trust and a faithful willingness to accept guidance. Failing these no assistance is possible. Friendship that is simply a refined gregariousness has no significance in his eyes. In the sphere in which he works, the rebuke "Woman, what have I to do with thee?" will be found to be neither harsh, inhuman nor unkind; for his loyalty will always be to the deeper truth and to the higher reality. Earthly ties will have no binding force except in so far as they are based upon the real, the true and the sincere. His presence among others, no matter how catastrophic in its effects, will be their greatest blessing, for it will help them to understand that it is the truth that makes us free, and that whatsoever tends to make us free, in the fullest and deepest sense, is true.

The completed man will have risen above all creeds, for these must ever be based on half truths, and the maps presented by the various religions will be of service to him only in assisting others to approach nearer to reality by the ways best suited to their position in the zone of being which they have reached.

Discussion and argument as to whether humans have free will or are controlled like puppets at the end of a string as fate decides, can only evoke interest among those who confuse the sphere of intellect with the sphere of experience, which includes the whole content of consciousness–the all, and not merely the flickering cinematograph of spot-light attention. The problem must forever remain insoluble for logical reasoning; and those. intellectuals and scientists who have not proceeded far enough along the path to reality to comprehend the subordinate nature of the thinking faculty, must be content to wait upon the process of growth. In the deeper regions of experience such a problem has no place. Intellectual speculation melts into a true understanding, and in the figurative language which alone can be helpful, life is seen to be a pilgrimage in which the falsehoods and make-believes of prosaic daily life fall away and the strangeness of an unsuspected situation more and more reveals itself. The position might be dealt with by the use of precise scientific terms, but though the ears of the learned would thereby be pleasantly tickled, the approach to the untellable would be no nearer. Logical thought cannot function in the seedbed of the unconscious in which it has its roots and from which it derives nourishment.

In this connexion we must disabuse our minds of the very prevalent arrogance which assumes that because we have invented the steam engine and the telephone we are in a better position to consider a problem of this nature than were the ancients. Such an idea is crude and childish. If comparisons between different periods of the time-process had anything more than a superficial value we might draw an exactly opposite conclusion. Our preoccupation with material forces has withdrawn our energies from the proper study of mankind-which is man himself. The scientific study of natural forces though it extends the activities of mankind does not deepen his experience. It leads him into a maze of insoluble problems but it can never put the clue Of right living into his hands, nor reveal to him the value of wisdom. No greater disaster can happen to any civilization than when it sets a higher value on the study of science than on the pursuit of wisdom. And if that statement be a truism it is undoubtedly a luminous one for our age.

The stoic philosophy, of which Marcus Aurelius was the great exponent, drew a clear distinction between the boundaries of necessity and the marches of freedom. Fate (Clotho) stood for the hard, deterministic framework of things which all must obey and only the fool defies. Destiny fulfilled an altogether different role. The longer talking beast lives and the deeper his investigation of the processes of consciousness, the more evident it becomes that life is guided only partially by the forces we rate as physical and invariable. When those forces have been obeyed and put into service, another order of influences discovers itself. Instead of fate we have to deal with destiny.

The position of the adult, very much though not entirely at the mercy of fate, and his position when some degree of maturity has been attained, may be roughly illustrated by a comparison between a car and an aeroplane. In the adult state man is controlled materially as is the track of a racing car, which has to depend on banking. At higher levels, as in the air, the banking has to be done by the agent himself. Self, even when it has attained to complete manhood has to submit to banking on the earth but must bank for itself when moving on higher levels.

For the modern, the important point to bear in mind is that freedom and its attainment, have very little to do with the logical, thinking mind. It depends on talking beast's efforts to move forward from the adult to the mature condition. His need to think logically is far less imperative than his need to live wisely. The thinking mind which should be an instrument of Self is too often used as an instrument of ego. The adult expression of personality and ego, has no conception of the beauty and the harmony of the promised land of freedom into which no feverish striving can lead him. For union with the real is not attained by striving but by humility, the first and last necessity, and by a frequent withdrawal from the market place: a statement which does not refer to any material forum. Noise is not in the market place nor quietness among the hills.

To satisfy the fantasy which adult man weaves about him, civilization would need to be static. It Would have to move from decade to decade without change or disintegration. And since the feeble-minded it end to the belief that all good and all evil are in the hands of governments to dispense, adult man would first have ccrtain acts of parliament introduced which would make life easier for himself and his class. Adult man believes that government can not only prevent the wicked man from being too wicked but that it can prevent wages from shrinking like ice-cream in the sun, and goods in the shops from soaring to prohibitive prices. Government, he supposes, can control moral and economic law and can, by passing the right enactments, provide work for everyone and the wage which each regards as "just." Naturally, holding such views, adult man takes an excited interest in politics, tending usually to the adoption of extreme views, heedless of the fact that extreme views are always false and usually harmful. Vague but attractive generalities flutter like beautiful butterflies just in front of his nose: Justice, Equality, Freedom, Progress, Reconstruction. He has heard someone say, somewhere that if only the millions a day poured out in time of war were poured out equally freely into the right channels in time of peace, we should speedily get rid of poverty, slums, dirt, disease, ignorance, vice and all the sufferings of the underdog. Feeble-mindedness is ready to accept almost any fantasy that stirs its emotions pleasantly by appeals to its ego-centricity. It is impatient of waiting. It wants the goods now, and so long as they have the right labels, is ready to take the contents at face value.

The poor animal in the adult talkative stage is not without virtues, but his stupidity almost completely nullifies them. He lives by catchwords because he has neither the capacity nor the inclination to find out the truth of things for himself. He is not concerned with truth. He is concerned with getting what he wants, like the beasts who have not acquired the faculty of talking. And every now and again Fate hits him a shrewd blow; now a clout over the head, now a kick from behind, until even indefatigable ego grows tired. And in the weariness of ego it is possible that the still, small voice of Self may be heard.

"Look within," wrote Marcus Aurelius, "lest you miss exact knowledge of things." (Meditations, vi, 3.) Such a warning must appear strange to modern ears. We of to-day are under the illusion that an exact knowledge of affairs can only be obtained by losing ourselves in the hurly-burly of activity which makes up modem living. The fallacy is pathetic in its results. Homo vulgaris imagines that to consciously relax or to look within is tantamount to the sin of idleness or the encouragement of morbidity; something to be left to those body-snatchers of the spirit, the psycho-analysts. The result is that he runs away from himself, in a great hurry not to look at what is inside him. The inevitable consequence follows. He has less and less of an exac t knowledge of the world; refuses to call things by their right names, and ends by creating a fantasy world of his own somewhat akin to that of the lunatic in an institution. In another passage of the Meditations, Marcus Aurelius wrote: "Search within. The spring of good is within, capable of continually gushing forth if you will always dig down." (Meditations, vii, 59.) It would appear, therefore, that in the experience of the great Stoic philosopher, an exact knowledge of affairs depends, not on a strenuous application of the reasoning faculty or on the ceaseless outward activity of the thinking mind, but rather on a withdrawal from the world without to the world within. In his philosophy, constructive quiescence is of greater practical value than even the most devoted altruistic activity.

At this point it occurs to me that I have made a serious mistake. I ought not to have referred to the "inner life" at all. The phrase must appear cold and chilly to man in the business age. It must appear about as cheerful and encouraging to him as one of those stone tombs with recumbent knights on top, in the silence of our beautiful deserted cathedrals. But I could find no suitable paraphrase. Possibly the Americans, who have modernized the Book of Wisdom into the Book of Wisecracks, may have such a phrase, but if so, I have not learnt it. All I can do now to make amends for this foolish blunder is to assure talking beast that there is nothing remote or queer or strange or morbid or mysterious about the constructive quiescence known to our forefathers as the inner life. Its cultivation results in a more receptive attitude towards the unconscious. We cannot, any of us, escape from the unconscious any more than we can escape from our skins. Every time we do a simple sum in arithmetic, such as 7 x 8 = 56, we are dropping a question into our unconscious mind and waiting for the answer. The answer was registered there long ago when as children we learnt our multiplication tables. But what actually goes on in the unconscious mind nobody can say, for no one can see himself thinking. The mathematician, the engine driver, the carpenter, all alike depend every moment on this process of waiting on what is in the unconscious to come into consciousness. We shall therefore do well to get rid of the prejudice that the inner life is concerned only with nunneries and prayer books and stuffy lives of the saints. It is a very practical matter, and the more we get to know about it the better for us. It is through Self, the agent of our unconscious mind, that all our best and highest impulses come.

Therefore we must guard our inner life as a dragon guards a treasure; we must see to it that no intrusions of the world hamper the activity of Self. Outward activity and the pressure of duties to be done will not excuse us for neglect of our inner life. The fool is driven by events, the wise man seeks to control them. He will not always be successful, but something will be attained by an honest effort to avoid the futile chatter of the market place. The greatest fee he will be called upon to meet in this connexion is impatience: impatience with himself and impatience with others. Impatience more than anything else spoils receptivity of the still, small voice of Self. Unless there be a fair measure of tranquillity in the life, a fair measure of freedom from mental and emotional disturbance, the higher guidance cannot operate.

The mind that rushes through books at top speed is the gregarious mind; the mind that cannot endure to be alone. But in any attempt to deliberately cultivate the inner life, loneliness will have, sooner or later, to be encountered. It is the dragon which guards the treasure.

But the treasure is great and its value is not only for time but for the condition beyond time in which Self has its being. Peace, harmony, courage and goodwill are not inconsiderable trifles. For the attainment of such gifts and graces it is worth while doing battle with the Dragon, Loneliness.

If all human beings consisted solely of personalities and egos there would be no possibility of any inner life beyond the vague inattention of day-dreaming. The purposeless dance of ceaseless activity expressed in so many zones of human life would fill the whole of man's existence, rounded off by the sleep of utter fatigue. But the presence of Self, known or unknown, accepted or denied, is a continual rebuke to such living. It flings out a challenge to futility and by bringing peevishness, boredom or ill-health to the individual, awakens it to some dim perception of the true position. Self never remains for long a silent or inactive witness. It makes its presence known either by the sorrow and suffering we attribute to' Fate or by the gentler guidance to which more sensitive souls can respond. Self speaks in a variety of voices, but its purpose is ever the same.. Personality and ego may be as assertive and refractory as they will, but Self is master. His patience is inexhaustible, for he is not concerned only with space-time consciousness. His defeat is an impossibility.

The need to face up to loneliness has been stated or emphasized in other connexions. It is necessary to return to it if we would assess the claims of society on the individual life. The term "hermit" has always and rightly been tainted with reproach. The human animal, it is felt, should not quit the herd in order to live unto himself alone. Too many hermits have been escapists and nothing more: just as too many pacifists have been escapists and nothing more. But it is essential to dear thinking that we should avoid generalization. Every problem should be considered on its own merits: There were never two hermits exactly alike. Whether St. Simeon Stylites was justified in spending his days on the top of a draughty pillar devoid of sanitation I cannot say. Even had I met this particular hermit the problem would have remained equally insoluble. As regards sainthood, we should judge by results and not by appearances or protestations. There have always been as many rogues and as many fools among the saints as anywhere else in society. But this fact does not exonerate us from the urgent need of seeking guidance. Better follow the wrong guide and fall into a ditch than live in a comfortable villa with modern conveniences in the dead atmosphere of surburbia or in a flat amid the smart futilities; of Mayfair. The fact that millions five in some such dead and meaningless routine gives no sanction to such living. In the kingdom of the real, which has also been called the kingdom of heaven, numbers have no significance. Thus we come to understand that in addition to the acquisitive inertness of ego and the bright plausibility of personality, the great foe to the inner life is the continually threatened inroad of society. If society were composed solely of Selves the position would be different. But obviously this is not the case. Society is composed of talking beasts, mostly in the crude, adult, feeble-minded condition. We. have at all times to remember, therefore, that in all our human relationships we are almost certain to be dealing with people in the adult stage–and the beast nearest to us will be ourself. But since the last illusion mankind refuses to give up is his belief in its own refinement and maturity, we can hardly hope to be aware of the position. In our relations with the untalking animals, we are under fewer illusions. We know their ways and can count with some certainty on their reactions. The dog must be trained, taken for walks, domesticated. We know quite definitely what the canine reactions to circumstance will be. The cat, ancient symbol of relaxation or of inertia, must be allowed a comfortable chair near the fire and must be sheltered from the violent caresses of the. little beasts who are learning to talk. If we have known one cat, we have known all. But other personalities are innumerable in their subtle and infinite variety. For personality is a mask to conceal not one secret but a million: some held consciously, some unconsciously. And the more we are under the illusion that personality is a real entity, a being created to live for one lifetime on earth or for an eternity of living, the greater and more confusing will our perplexities become. The key to our bewilderment can only be found in the knowledge that personality is no more than a spacetime nucleus of faculties, hereditary, environmental and atavistic, which can have no enduring existence, no permanent value. Until we have learnt and know beyond all preadventure that humans are linked with all other orders of animals in the synthesis of being; that they are inevitably ignorant, complacent, often hostile, frequently centres of irritable disturbance, seeking sometimes to dominate by force of will, sometimes to Placate by friendly smiles devoid of true goodwill; until we realize this and cheerfully accept the situation, we shall be at a continual disadvantage in society. For society is always trying to have its way with us; to lure us into that meaningless vortex of surface activity in which it whirls; to force us to subscribe to all its hypocrisies and to bow to all its false ideals. Yet we may not dissociate ourselves from society. It is the space-time arena in which Self must find a means of executing its trusteeship towards others, respecting always their freedom and therefore ready always to withdraw and seek an outlet for its activities elsewhere. But society must never be allowed to deflect Self from its course; for Self has nothing to learn from society though society has a great deal, to learn from Self.

To the modern mind, however, accustomed to ideas which have crept into daily speech from the vocabulary of psychology, the attitude of mind called waiting, or acceptance, best describes the core ' of the inner life. As has been pointed out frequently before in these pages, we live by unconscious processes. Our tenuous consciousness looks for and receives authoritative guidance from sources of which it is unconscious until the message is received in consciousness. The process is the same whatever the subject may be, whether logical movement, moral command, stored up facts and principles, simple mathematics or spiritual direction. When once the question has been set in tenuous consciousness, however sharply, however dimly, however reluctantly, the new perception arrives only after patient waiting.

Our forefathers were much concerned with the idea of inspiration. They held that certain scriptures were inspired and others not. Knowing nothing about the manner in which consciousness works, mistakes and confusions were inevitable. They did not understand that all writing is derived from the unconscious mind, Cobbet, when asked how he wrote, replied that he wrote at the point of his pen. He never knew, he explained, exactly what he was going to say until his pen moved over the paper. It came into consciousness and he set it down. All that any writer can do, so far as his conscious mind is concerned, is to think about the subject with which he is to deal. When it comes to the actual setting down of words on paper, he can only wait on the ideas hidden in the darkness of the unconscious mind. Inspiration is simply the old word for this waiting on the unconscious. Naturally the matter received varies very considerably in moral and spiritual value according as it is received by a talking beast in the crude, adult stage or by one who is more mature, or by that transcendent being who has attained complete manhood and is no longer an unfinished animal awaiting development at the hands of his creator. The "inspired" scriptures derived from a Jesus, a Buddha or a Marcus Aurelius have in them the pure essence of Self universal undiluted by the alloy of ego and personality. But they were all received by precisely the same means as that by which a child receives the information that two added to two make four. There is no mystery in the reception of even the highest degree of inspired wisdom. Neither does it come haphazard. In the adult state the writer can produce fiction of absorbing interest and high artistic value, but he cannot write above. the level of his own consciousness. The law in this matter is fixed and unalterable.

If anyone nourishes the illusion that the, inner life or life of waiting on unconscious processes is a vague, unpractical abstraction, his thinking must be crude indeed. Nor ran waiting be regarded as an additional ornament to a conventional prosaic life. The orthodox religious certainly have not a monopoly of it. From moment to moment we all live by it and cannot live by any other means. Even the most frivolous piece of modern fluff cannot exist without an inner life. To powder its shiny nose at the right moment cannot be done without assistance from the inner life of the unconscious. Consciousness can effect nothing beyond the arrangement of unconscious material.

We can never escape from our accompanying unconscious in life or in death. It is highly necessary therefore that we should seek to understand the position and to make friends with the unconscious in all its reaches. Self, the agent of the unconscious, the unknown directing force of our life, is always with us. "If I go up into heaven thou art there, and if I go down into hell thou art there also."

Owing to the directive agency of Self the inner life is full of promise and is the only means by which our true advancement can be attained. In the adult stage we question whether the human race ever really improves. Men, we aver, are as wicked and cruel to-day as in the days of Nero. Such a comparison is wholly misleading. To consider such a short span is equivalent to arguing that a man never grows older because no change can be detected in him when only the morning and the evening of a single day are taken into account. But if you compare the adult of to-day with adult of a far distant geological era, you will be sensible of an enormous difference If you doubt my statement go to the Zoo and have a look at the anthropoid apes.

Looking at that monkey, so like and yet so different from ourselves, and having regard to our own unfinished state, we have to accept the fact that the, creator is still creating and that this work of creation takes place through the agency of Self. In considering the inner life or life in which we wait upon the unconscious, we come to a very practical conclusion. In the language of slang, we come down to brass tacks.

The adult suffers continually from a lack of power, a lack of certainty, a lack of authority. For the most part he feels himself to be helpless as a straw in an eddy of swirling water. If to-night he regards himself as a good fellow, in, the morning he is ready to admit that he is a miserable sinner. He lacks direction, he lacks confidence, he lacks the growing enlightenment of wisdom. His natural forces are dissipated in the struggle to exist; in efforts to amuse himself during cessations of that struggle; or in the usually vain task. of attempting to help others who appear in even worse case than himself. Even his efforts to enjoy himself are rendered abortive because he puts his whole trust in the thin, tenuous consciousness which is concerned only with the surface of things. And yet the source of all power and all endurance and all understanding is near at hand if he would make the effort to adjust himself to his true position. Power to live a deeper, fuller, more effective life; enlightenment concerning those fundamental problems which confuse and daunt him; authority which can exercise the leadership of Self but not of ego; all these may be his if he will deliberately turn the forces of his inner life into constructive channels. The high-powered, internal combustion engine of to-day runs smoothly and efficiently because all its parts, simplified and modified by experiment, are directed to one single end. By careful lubrication, friction is reduced to a minimum. So should the inner life of those who are no longer feeble-minded become. They should know at what they are aiming and bend all their efforts to its attainment.

SCIENCE: FRIEND OF SELF OR INSTRUMENT OF EGO

Science (which is the modern term for knowledge) comprises the sum of all that human beings have discovered by means of their sense perceptions. Not even the most profound study of science can ever bring satisfaction to an ardent spirit seeking enlightenment as to the purpose of life, or a better understanding of his own being. Science, as understood to-day, is confined exclusively to the world of material appearance. What the eye does not see, the ear hear, or the other senses give knowledge of, does not exist for the purpose of science. If investigation seeks to press forward into any deeper sphere, then it quits the region of science and enters the land of speculation. The nineteenth century scientists found so much to occupy them in the study of sense-perceived matter that they had, little inclination for speculation. They regarded the reasoning mind as the complete mental apparatus and had no perception of the unconscious process breaking in to upset or modify their investigations. Space and time they regarded as definite, fixed entities, and eternity as a sort of fixation of time, a fiction created by poetry and religion. Their growing preoccupation, during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with machinery and the laws of mechanics led them to investigate the universe as though it were a vast machine.

The most modern scientific thought is inclining to the theory that time and space have no independent existence but are a creation of consciousness, the two ideas being interdependent. Thus from birth we grow into conceptions of passing time and limiting space; conceptions which are without fundamental reality and are no more closely related to the truth of things than is human speech.

The mechanistic theory of the universe has proved wholly inadequate. The universe can no longer be regarded by intelligent thinkers as a machine. No machine has consciousness; no machine can beget other machines as animal forms beget animal forms. There is only the most superficial resemblance between a locomotive and an elephant, between an armoured tank and a tortoise. The likeness is on the surface; the dissimilarity is fundamental. When Mary Shelley wrote her famous novel, "Frankenstein," she revealed herself to be a true child of her age. No writer of modern scientific fiction could appeal to the intelligent reader of to-day by such a crude venture into the regions of speculative science. The phenomena presented to. us under the aspects of time and space are no longer regarded as parts of a complicated machine but rather as a thought in some all-creative mind. , Thus Sir James Jeans quotes Bishop Berkely in this connexion: "All the choir of heaven and furniture of earth, in a word all those bodies which, compose the mighty frame of the world, have not any substance without the mind. . . .So long as they are not actually perceived by me, or do not exist in my mind, or that of any other created spirit, they must either have no existence at all, or else subsist in the mind of some Eternal Spirit." And Sir James's comment on the passage is as follows: "Modern science seems to me to lead by a very different road, to a not altogether dissimilar conclusion. . . .It does not matter whether objects 'exist in my mind or that of any other created spirit' or not; their objectivity arises from their subsisting 'in the Mind of some Eternal Spirit.' "

If these reflections should lead any reader to suspect that the present writer is inclined to belittle the findings or the achievements of scientific research, he is greatly mistaken. Between birth and death we are destined to live in a world controlled by the all-compelling fiction of time-space. From that fiction we can never for a moment escape so long as we are clothed in a garment of flesh. Therefore it is no less our duty than our privilege to learn as much as we can, on the level of consciousness, about the construction of consciousness which forms the stage on which we and, others play our parts. To vary the metaphor, the workman must have a practical acquaintance with his tools if his activity is to be effective. The tool nearest to consciousness is the body; our own body. The more we know about ibis body and the more obedient we make it to the higher aspirations, conscious and unconscious, the more actively creative will our lives become.

The danger confronting us as regards scientific investigation and development, is the old menace of laisser-faire and of effort vitiated by, if not prompted directly by, egoism. These tendencies have almost wrecked modern civilization. Science and its products can be put to many uses; they can only be put to one legitimate and wholesome use. if science is not deliberately made the handmaid of Self, it will inevitably degenerate into becoming the abject slave of ego.

Scientists are for the most part, it may be objected, men of noble mind and high purpose. That is true. But the discoveries they bring to birth very speedily pass out of their hands. The machines they construct almost immediately become articles of exchange–"goods" to be bartered in the market place. The scientist in his laboratory, no less than the engineer in his workshop, is inspired to pursue his researches by the desire for fulfilment and perfection. It is far otherwise with the dealers who sell his devices to the highest. bidder. Machines whose skilful design and execution only the' expert mechanician can appreciate, become the toys of a thoughtless multitude or the destructive tools with which the most debased and unscrupulous talking beasts wage aggressive war. The menace is not from the scientist who invents or the physicist who investigates but from the vast multitude of greedy, thoughtless traffickers in the adult condition of feeble-mindedness. They are like pigs that rush to the trough directly the swill is poured in, struggling and squealing, in frantic efforts to push away the others. This is but a crude analogy of what is always going on in the modern state. But the civilization of to-day is so complicated that it is difficult to detect the motive behind the act. Very few things are called by their right names (i.e., for. "religion" we should usually read "fanaticism" or "convention": for "kindness" we should often read "self-indulgence" or "self-pity" : for "friendship" we should often read "self-interest" or "gregariousness"); and thus it happens that the weak, the unintelligent and the vicious are easily misled. Even commerce and money-making suffer from the obstructive opposition of vested interests, and the way to new developments is barred. Many money-saving, health-saving or time-saving devices would have come into being were it not for the dead weight of commercial interests which have blocked the way. An interesting book might be written about inventions and discoveries that have been nipped in the bud by wealthy manufacturers ready to pay any I price to buy up patent rights rather than lose their market. Who has not heard of the electric lamp in which the filament would last a hundred times longer than any now in use; of the match that could be struck and used over and over again; of the gramophone record that could be run at a far lower speed than those now on the market; of a face-cream. that would remove hair on the skin and render shaving unnecessary, thus throwing hundreds of barbers out of work? Some of these tales are inventions, some exaggerations, but some are true. The greed of the manufacturer is not likely to be modified by any care for scientific development or social amelioration. His eye is fixed on one mark and on one mark only; big business and the wiping out of all rivals. And if you told him that the inventions and discoveries of scientists ought not to be prostituted to greed and gain, he would laugh in your face. For of all tough talking beasts the manufacturing beast is among the toughest and stupidest.

Thinkers of the nineteenth century fell into the curious error of believing that scientific discovery must be a benefit and lead to nothing but good results. The multiplication of machines, they argued, must lead to' better conditions all round. Only the multitudinous toilers who found themselves without work, had doubts of the promised millennium. In blind anger they smashed many of the machines. But there is no setting the clock to go backward in this time-space world. The tempo increased. Time was saved; space contracted; the few grew wealthy; the conditions of the many improved. And yet, despite the amazing changes, nobody appeared much happier; the age-old problems still remained unsolved. The fact that one could travel from London to New York in a week instead of in five or six weeks brought many, advantages. It did nothing to alter the fundamental facts of the human lot. Men still knew sorrow, suffering and despair. For a brief period,, the age of science eluded itself into the belief that it was approaching Utopia. Then came war; war which science had so thoroughly equipped that it could no longer be kept at a respectful distance from the women, the children, the old and the sick; war that dropped high, explosives from the sky and sent forth armoured landships that only the biggest guns could disable. And with the coming of these scientific developments mankind began to realize with a terrible sinking of heart, that he still belongs, not to an order that is far in advance of the animal creation, but that he is himself no more than an animal although he has acquired the faculty of speech and the untrustworthy guidance of reason. His passions, he finds, arc still the passions of the jungle; his fears, the burrowing timidities of the rabbit.

This would have been a depressing discovery indeed had there been no indication of further progress open to the beast that talks, but so evidently lacks finish. The creator, however, who is ever creating, does not hide himself in the backward mists of time, or in the contradictions of science; nor need he be sought only in the confused or fanatical voices of changing religious cults. Self speaks from the region of the unconscious, from a region where time and space are dreams, and where knowledge is no longer needed because experience can be known. Under the guidance of Self, slowly and with many set-backs, the work of creation has gone forward. The human form has been gradually improved; the branch-clutching forefeet have become the competent hands of the craftsman and the sensitive fingers of the artist and the surgeon. In obedience to the creative impulse talking beast has learnt to build cities and to equip himself with machines so that what is within him may be expressed in outward form.

In no civilization has mankind in the mass attained finality or finish. And therefore it would be ridiculous to suppose that the machines he has devised could bring him gain without loss, or happiness without sorrow. These gifted ones who talk and tor ape ancestors. They are still as clay in the hands of the potter or as dream-stuff haunting the consciousness of the writer or musician. But to make this statement is not equivalent to saying that no member of this tribe has yet attained completeness in the flesh. Those who have, in their journeys between birth and death, come into personal contact with such completeness, are not many. Yet there is no unfairness in this arrangement. Leadership is diffused throughout many levels. The sun does not shine equally brightly on all landscapes though it is absent from none. In every civilization, in every age, in every level of human society, the law operates that those who seek, humbly and with determination, shall find; that those who plant shall reap in due season. Spiritual gifts are not bestowed as the result of chance or favour. They are the fruit of patient work in the difficult fields of consciousness and conduct. Nor is historical testimony, in its broad aspect, without witness to the facts as stated. If any toiler, caught in the ceaseless stress of competitive struggle, clings to an obstinate doubt of what is here written, or seeks to belittle its importance, let him withdraw from the confusions and compulsions of life even for those brief moments of inactivity denied to none, and read the closing pages of the Phaedo of Plato. In this way he may put himself in touch by means of the written word with a member of his race who was no longer an unfinished animal but had attained complete manhood. My purpose in indicating Socrates rather than Jesus or Buddha or Confucius is to avoid religious preconception and ecclesiastical prejudice. The religions into which we are born and in which we are nurtured, no matter how true or how exalted, are inevitably mingled with much alloy of forceful personalities; nor do many of us find it easy to free ourselves from the many prejudices thus imbibed. Socrates founded no religion, Plato established no church. Yet in these illuminative teachings are enshrined the basic spiritual foundations of all true religion.