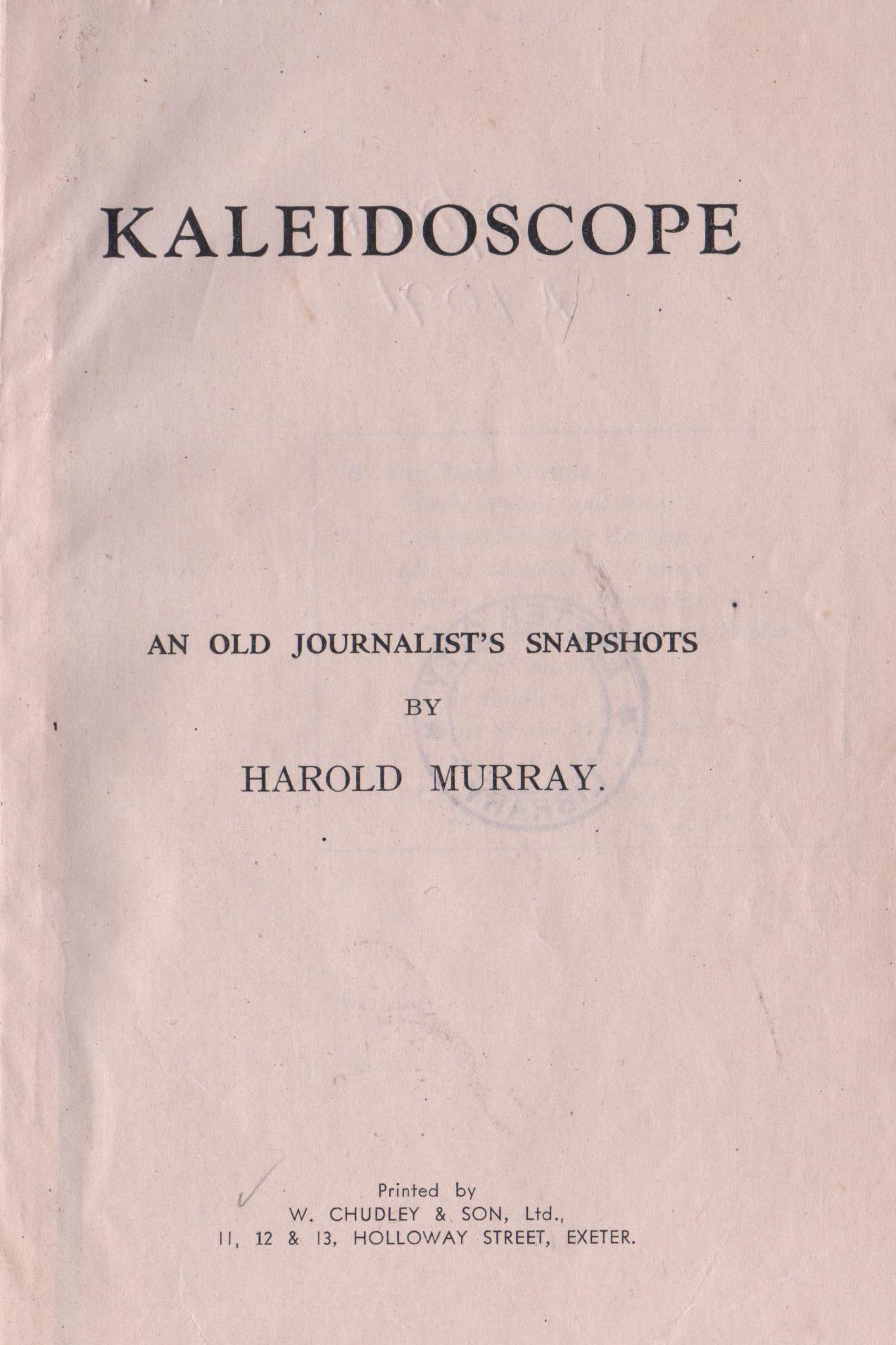

PHILIP LARKIN. ( The Times Educational Supplement, July 13th 1956)

It’s just over a century since Philip Larkin was born. Quite rightly, since he is a major poet, radio and TV have been crowded with tributes—four programmes in one evening a couple of weeks ago—and reassessments on Radio 4 from the man who now holds the post that Larkin politely declined—Simon Armitage, the Poet Laureate. There have doubtless been meetings of Larkin enthusiasts around the country and in May one major symposium ( which your Jotter attended) held by The Larkin Society in Hull as part of an Alliance of the Lit erary Societies weekend.

erary Societies weekend.

So the legacy of Larkin is very much in the minds of poetry lovers at the moment and luckily for us, the literary archive left behind by the former academic Patrick O’ Donoghue , contains two clippings —one anonymous portrait in the Times Educational Supplement of the poet following the publication of his first major collection, The Less Deceived—and a full review by D .J. Enright of his second slim volume, The Whitsun Weddings.

This first Larkin Jot considers the TES profile. Here, the anonymous profiler describes him as ‘ one of the most successful poets of his generation’ , which seems a slight exaggeration, since following the underwhelming The North Ship of 1946 he had only published a privately printed pamphlet XX Poems in 1951, which ( like Auden with his privately printed Poems of 1928) he sent free copies of to ‘ most of the leading figures of this country’, and a thin Fantasy Press pamphlet in 1954. Both are now hard to come by.It is true that The Less Deceived had run into three editions within nine months, but can this one success make him ‘ one of the most successful poets of his generation ‘? Mind you, two possible rivals, Kingsley Amis and Donald Davie ( remember him?) who were also born in 1922, could hardly be described as ‘ successful ‘, if successful means popular and highly regarded by 1955. Charles Causley and ( ) might have been rivals, though.

Be that as it may, the profiler is surely correct in describing The Less Deceived as

‘ as sharp an expression of contemporary thought and experience as anything written in our time, as immediate in its appeal as the lyric poetry of an earlier day, it may well be regarded by posterity as a poetic monument that marks the triumph of clarity over the formless mystification of the last 20 years ‘.

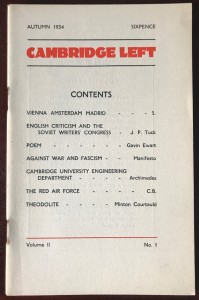

Larkin is credited with bringing poetry back to the ‘middle-brow public’. It would be nice to know who this anonymous profiler was, for surely the immediate success of The Less Deceived was partly due to a reaction by the poetry-buying public to the mystification wrought by the Apocalypse school of Nicholas Moore, Henry Treece al and the abomination that was The White Horseman. The Movemnet was partially a reaction to this obscurantism , but Larkin was never really part of it. He did not contribute to such a periodical as New Lines, but he was doubtless in sympathy with its aim.

What comes across strongly in the profile is Larkin’s resignation to his lot as a career librarian who writes poetry in his spare time but who is not an amateur. Continue reading →

Found among the papers of the academic Patrick O’Donoghue, two clippings of reviews—by Philip Toynbee and Cyril Connolly—of The Outsider (1956), the astonishing debut of the twenty-four year old, largely self-taught, Colin Wilson that branded him a fully paid up member of the Angry Young Men brigade and ‘ Britain’s first, and so far last, home-grown existentialist star’.

Found among the papers of the academic Patrick O’Donoghue, two clippings of reviews—by Philip Toynbee and Cyril Connolly—of The Outsider (1956), the astonishing debut of the twenty-four year old, largely self-taught, Colin Wilson that branded him a fully paid up member of the Angry Young Men brigade and ‘ Britain’s first, and so far last, home-grown existentialist star’.

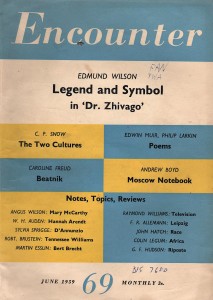

By the time The Whitsun Weddings had appeared in 1964 Larkin had become a major voice in contemporary poetry. As such he deserved a decent reviewer and he got one in D. J. Enright, a poet and critic two years older, who had reviewed XX Poems. The irony ( if that is the right word) is that the review of The Whitsun Weddings appeared in the New Statesman. Fast forward to the furore that accompanied the biography by Andrew Motion and the published letters edited by Anthony Thwaite, when left-wing readers of the ‘Staggers’ were among those who denounced the racist and xenophobic attitude of Larkin that he must have held at the time when The Whitsun Weddings came out. Of course Larkin, being Larkin, had kept his politics and racism out of this second collection.

By the time The Whitsun Weddings had appeared in 1964 Larkin had become a major voice in contemporary poetry. As such he deserved a decent reviewer and he got one in D. J. Enright, a poet and critic two years older, who had reviewed XX Poems. The irony ( if that is the right word) is that the review of The Whitsun Weddings appeared in the New Statesman. Fast forward to the furore that accompanied the biography by Andrew Motion and the published letters edited by Anthony Thwaite, when left-wing readers of the ‘Staggers’ were among those who denounced the racist and xenophobic attitude of Larkin that he must have held at the time when The Whitsun Weddings came out. Of course Larkin, being Larkin, had kept his politics and racism out of this second collection.

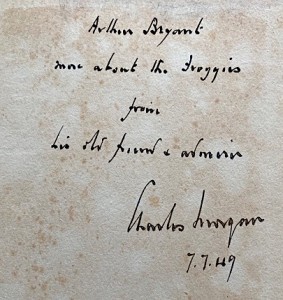

Connecticut 1928) – a special American edition. The great historian ‘s paean to the joys of walking (” I have two doctors, my left leg and my right..’) was published first as an essay in 1913 in Clio, a muse, and other essays literary and pedestrian and the American introduction by J. Brooks Atkinson notes that the walking world has changed much since then: “..the motor car has completely separated the walkers from the riders. It lays a new responsibility upon the walkers to conduct themselves nobly in God’s light.. they cannot be road walkers now, like Stevenson, since roads have become arteries -hardened arteries- of traffic. They are pushed willy-nilly into the hills, meadows and woods beyond the clatter and the evil fumes of the highway..” (he then launches an attack on the new walking clubs- ‘their walking is a bastard form of motoring.’) Trevelyan’s essay recalls a world now largely lost, although our great modern walkers (Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane, Will Self) still find great places to ramble. GMT writes:

Connecticut 1928) – a special American edition. The great historian ‘s paean to the joys of walking (” I have two doctors, my left leg and my right..’) was published first as an essay in 1913 in Clio, a muse, and other essays literary and pedestrian and the American introduction by J. Brooks Atkinson notes that the walking world has changed much since then: “..the motor car has completely separated the walkers from the riders. It lays a new responsibility upon the walkers to conduct themselves nobly in God’s light.. they cannot be road walkers now, like Stevenson, since roads have become arteries -hardened arteries- of traffic. They are pushed willy-nilly into the hills, meadows and woods beyond the clatter and the evil fumes of the highway..” (he then launches an attack on the new walking clubs- ‘their walking is a bastard form of motoring.’) Trevelyan’s essay recalls a world now largely lost, although our great modern walkers (Iain Sinclair, Robert Macfarlane, Will Self) still find great places to ramble. GMT writes:

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes:

Found among some papers at Jot HQ, three photocopied pages of a panegyric by poet William Oxley to his better known poet and friend Hugo Manning (1913 – 77). Entitled ‘ The Scapegoat and the Muse ‘ it lavishes praise on a man who appears to have been a larger than life character in the mould perhaps of his friend Dylan Thomas, who was his junior by a few months and from whose work he drew inspiration. But Manning, in Oxley’s eyes, seems to have been an amalgam of so many attributes: Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst

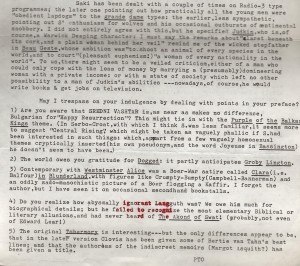

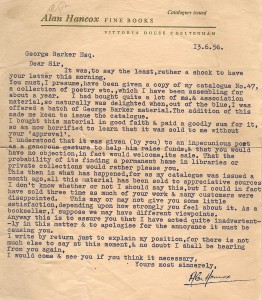

Banned books: No 12: Lummox by Fannie Hurst Found, a letter dated 6th December 1990 from someone called Rudi to the playwright John Osborne, whom he addresses as ‘ Colonel’, presumably a reference to Colonel Redl, the protagonist of Osborne’s controversial play A Patriot For Me (1965).

Found, a letter dated 6th December 1990 from someone called Rudi to the playwright John Osborne, whom he addresses as ‘ Colonel’, presumably a reference to Colonel Redl, the protagonist of Osborne’s controversial play A Patriot For Me (1965).