Found in a box of ephemera are some pages from a feature entitled ‘The Fore-Edge Painter ‘, which was published in a early fifties issue of Lilliput magazine. The piece is about a professional antique- faker who is introduced by an antiquarian bookseller to ‘Gulliver’, who wants to know the tricks of the forgery trade.

Found in a box of ephemera are some pages from a feature entitled ‘The Fore-Edge Painter ‘, which was published in a early fifties issue of Lilliput magazine. The piece is about a professional antique- faker who is introduced by an antiquarian bookseller to ‘Gulliver’, who wants to know the tricks of the forgery trade.

The piece is doubtless semi-fictional and was probably contributed by a dealer or collector familiar with the tricks of the forger which, by the way, is still very much alive, the most astonishing recent example being that of Sean Greenhalgh, the brilliant art student dropout who fooled ‘ eminent ‘ West End dealers and museum professionals with artefacts created in the garden shed of his council house in Bolton.

In this Lilliput feature the faker is described as ‘ a foxy little man with a red knobbly face, sandy hair and cunning hazel eyes ‘—a bit of a cliché that, since most forgers look like the average Joe, and indeed Greenhalgh has the face of a fifty something football fan you might find in the public bar of a pub outside Old Trafford.

Anyway, ‘knobbly face’ begins his presentation by producing an early nineteenth century volume and manipulating it with thumb and finger to show the fore-edge painting. He then announces that this was a fine example of ‘Genuine Edwards double fore-edge painting ‘which he had picked up at a country sale the week before. Unimpressed by the spiel the book dealer offers £5 for the volume. The faker accepts the money, but protests that if the painting was really by Edwards it might be worth up to £200.

He then produces a single sheet of notepaper which on close inspection appears to be a letter dated 1837 from Charles Dickens to his friend and biographer John Forster. This too turns out to be another of his fakes. And there are more. A letter in a vigorous hand on roughish paper appears to be by Robert Burns until the faker reveals that he wrote it himself in ox-gall obtained from his butcher on a flyleaf removed from a mid eighteenth century book.

Finally, comes the piece de resistance. The faker reveals that on one occasion he picked up a first edition of Johnson’s Dictionary for five shillings:

‘…I inscribed it on the fly-leaf as a presentation copy from Johnson to Boswell…Made a nice little ‘association item’ as they call it in the trade. Bookseller gave me twenty-five bob for it. Trouble was, I’d run out of ox-gall so I thought I’d try permanganate. Gives a lovely antique brown tint at first, but it only lasts a few weeks’

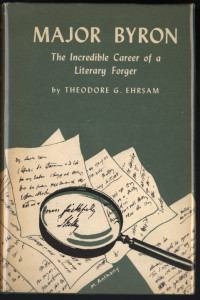

Indeed so. In contact with air potassium permanganate oxidises into manganese dioxide, which is known to artists as umber, and is still used to ‘age’ theatrical props. The forger then boasts that he could copy the hands of many famous writers, including Coleridge, Byron, Thackeray and Tennyson and had sold fake letters in their handwriting by pasting them into old albums and peddling them around towns on the south coast. Using the same sales talk technique employed by Greenhalgh’s father decades later on his trips to auction houses and art dealers, it went something like this: ‘ I’ve got a rather interesting looking album here that was given to me as a boy by an old family friend…I don’t know whether any of these letters are worth anything…’ In Bournemouth alone he had made a hundred quid.

Other fakes created by the anonymous craftsman included ‘sixteenth century’ horn books made from old ( ?mica) picnic cups, some documents made from the skin of an old drum, and an early nineteenth century brolly picked up in the old Caledonian market and provided with an inscribed silver band that told of its being given as a present from Emily Bronte to her sister Charlotte.

Compared with the inept art forgeries of Tom Keating that made the headlines in the seventies these documents and artefacts appear to have been most convincing, if we are to believe the testament of a criminal. I myself have come across at auction albums of letters purporting to be from nineteenth century figures and have convinced myself that no forger would bother to fake the hand of a minor individual and that any letter bearing a printed address must be genuine. Caveat emptor.

[R.M.Healey]