It’s bad enough to learn that nineteen British prime Ministers attended Eton College without learning recently, as I did, that one Eton man was so enamoured of the benefits of a classical education that he seriously suggested that Latin and Greek were the only subjects that should be taught in the classroom.That man was not, incidentally, Boris Johnson, but Edward Balston.

Balston—the son of William, that famous papermaker familiar to all students of palaeography—attended Eton in the 1820s and early 30s and then entered King’s College, Cambridge in 1836. Awarded the Browne Medal for Latin verse every year from 1836 to 1839, he was unusually elected Fellow of King’s in 1839, two years before he graduated, though why it took him five years to gain his B.A. is not adequately explained. In 1842 he became a priest.

Balston loved Eton so much that he couldn’t wait to return there. In 1840, before he had even graduated, he became an assistant master at his alma mater. Twenty two years later he was chosen as Head. In July 1862, not long after his appointment, Balston came up before the Clarendon Commission on Education. On hearing his views on the primacy of classics in the classroom Lord Clarendon was appalled:

Nothing can be worse than this state of things, when we find modern languages, geography, history, chronology, and everything else which a well educated English gentleman ought to know, given up in order that the full time should be devoted to the classics; and, at the same time, we are told that the boys go up to Oxford, not only not proficient, but in a lamentable deficiency in respect of the classics.

Balston countered by explaining that he did allow occasional lectures on science at Eton and conceded that French might be made compulsory. But on the whole he felt that in most lower forms of the school only Latin and Greek should be taught. Perhaps these views did not go down well with the parents, most of whom would have been in favour of a much broader education for their sons. After just six years as Head Balston left Eton for a new life in a rural parish.

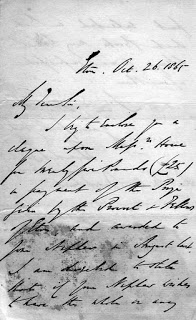

Our featured letter, which is dated October 26th, 1865 belongs, however, to a happier period for Balston and shows him carrying out his duties as Head to perfection. The letter is addressed to a Reverend M. H. Buckland and discusses the award of a prize---doubtless for a boy’s prowess in Latin or Greek. It once enclosed a cheque for £25 given by the ‘Provost & Fellows of Eton’. To their credit, the latter did not rule that the money be spent in a certain way, but if the prize-winner decided 'to have the whole or any part expended on Books, such Books may have the College arms impressed upon them'.

So once again Balston, with the reputation of the College uppermost in his mind, ensured that anyone spying these books in the future would instantly know which school the prize-winning scholar had attended! However, I wonder what he would have done if the classicist had decided to spend his money on a set of Dickens.

[R.M.H.]