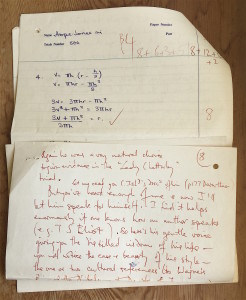

Found among the papers of the mathematician Norman Routledge (1928-2013) this affectionate memoir of E.M. Forster. Routledge had known Forster in the 1950s when he was a Fellow at King’s College, Cambridge. He went on to become a distinguished teacher of mathematics and was a close friend of Alan Turing, inheriting some of his books. The second half of his working life was spent teaching maths at Eton. These notes were probably for a talk he gave to the boys there (mid 1960s) with a sound recording of Forster talking (probably this piece from YouTube) and some reading from his books. The notes are written on the back of the maths homework of one Hope-Jones minor…

Found among the papers of the mathematician Norman Routledge (1928-2013) this affectionate memoir of E.M. Forster. Routledge had known Forster in the 1950s when he was a Fellow at King’s College, Cambridge. He went on to become a distinguished teacher of mathematics and was a close friend of Alan Turing, inheriting some of his books. The second half of his working life was spent teaching maths at Eton. These notes were probably for a talk he gave to the boys there (mid 1960s) with a sound recording of Forster talking (probably this piece from YouTube) and some reading from his books. The notes are written on the back of the maths homework of one Hope-Jones minor…

I wish I was going to tell you about a great hero- figure, spouting brilliant and amusing things, and combining an amazing literary fertility (an earth-shaking novel every year) with great and noble deeds -what should they be? – fighting injustice and involved in passionate love affairs? But he is none of these.

He happens to have lived since the war in the college, Kings, where I was an undergraduate, and so one would occasionally meet him on social occasions. He’s rather non-descript in appearance – has a moustache and rather dowdy clothes and speaks very little but listens a lot. Very gentle eyes. Is greatly loved by all who know him– has indeed the air of always having been loved without having had to strive for it. Can be very amusing if he wishes, but you have to listen carefully– I’ve seen people quite fail to notice that he has been making fun of them.

Loves being amused –loves hearing gossip especially the slightly scandalous nature– any story which illustrates the variety and deviousness of human nature and the deflation of the pompous. But despite the gaiety, the charm, one gradually realises his fundamental preoccupation is with moral questions– what constitutes good actions. Even his interest In culture, – music, painting, poetry as well as literature, has, I think, a moral origin. The importance on the arts is that they make us more sensitive to real life. And I fancy his famous “silence” – the fact that since 1910 he has written only one novel A Passage to India derives from the fact that the novelist must strive to disguise his moral messages with the exigeances of the plot…

Since 1910 he has pursued his interests and ideas (in the main) directly without moulding them into novels– he has written a stream of essays, which combine charm with a hard-core of thought and reflection. Luckily these are collected into two convenient volumes Abinger Harvest and Two Cheers for Democracy.

There follows some literary discussion of these works and a summary of his life which is available from many sources.) Routledge adds:

…he also joined the Apostles (The Longest Journey is dedicated to them -‘fratribus’.) They were a high-minded, secret discussion group which still continues and he was active in until very recently ( his deafness makes him avoid crowded rooms.) Otherwise he has lived in Abinger, London and Cambridge, visiting and being visited by his friends, listening, joking, and gently raising his voice when he thinks there is something worth saying e.g. when Andre Gide, the distinguished French writer, died and The Times in his obituary failed to mention that he was a homosexual (indeed was the first writer to discuss this matter seriously) Forster wrote gently to reprove them. Again he was a very natural choice to give evidence in the Lady Chatterley trial.

But you’ve heard enough of me and now I will let him speak for himself. I find it helps enormously if one knows how an author speaks —here’s is gentle voice giving you the distilled wisdom of his life… you’ll notice the ease and beauty of his style and the cultural references… also notice the gentle humour even at the saddest moments’s his voice seems delicately amused and also note the occasional schoolmistress voice. You also notice the careful qualification of everything he says – no slick easy answers for Forster.