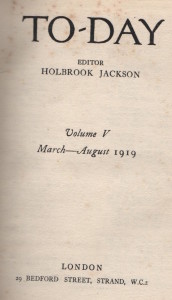

Found, in the issue of Today for March 1919, is this well argued plea by the acclaimed journalist Bernard Lintot for a greater appreciation of prose:

‘One of the most persistent of literary illusions is that the writing of prose is easier than the writing of verse. The contrary is the truth in both instances. Most of those who try can write passably good verse, and most of those who try fail to write passably good prose. Further there are far more triers at verse than at prose. Why? In the first place those who think they can write prose rarely pause to consider whether they are writing prose, because prose is popularly assumed to be all that writing which is not verse. In the second place verse writing is the more primitive, and therefore the most instinctive, and therefore, again, the easier form of literary expression. This, you may say, is mere theory. So it is. But, as theories go, it is none the worse for that, and as for facts, it is only necessary to point to the epidemic of verse-writing in full flux at this very moment. Never were there so many volumes of verse; never so many verse-writers, and those who succeed in bringing their composition to printing-point are in the minority of those who use or abuse metre and rhyme for the purpose of expression or amusement or vanity. The remarkable output of verse and poetry at the present moment is perhaps a little abnormal, but it certainly indicates a hitherto unsatisfied taste for this form of literary composition.

‘One of the most persistent of literary illusions is that the writing of prose is easier than the writing of verse. The contrary is the truth in both instances. Most of those who try can write passably good verse, and most of those who try fail to write passably good prose. Further there are far more triers at verse than at prose. Why? In the first place those who think they can write prose rarely pause to consider whether they are writing prose, because prose is popularly assumed to be all that writing which is not verse. In the second place verse writing is the more primitive, and therefore the most instinctive, and therefore, again, the easier form of literary expression. This, you may say, is mere theory. So it is. But, as theories go, it is none the worse for that, and as for facts, it is only necessary to point to the epidemic of verse-writing in full flux at this very moment. Never were there so many volumes of verse; never so many verse-writers, and those who succeed in bringing their composition to printing-point are in the minority of those who use or abuse metre and rhyme for the purpose of expression or amusement or vanity. The remarkable output of verse and poetry at the present moment is perhaps a little abnormal, but it certainly indicates a hitherto unsatisfied taste for this form of literary composition.

* * *

The volumes are read, it is true, very largely by those who have written, are writing, or would like to write, verse, and the fact that many more of them (volumes, not readers ) are issued than volumes of prose, say genuine prose essays, novels or plays, proves that verse is more popular than prose. But, you object—and there is as much meaning in your ‘but’ as there was virtue in Touchstone’s ‘if’—what about the newspapers: are not they very prose of very prose, and popular? What, again about Sir Hall Caine and Mr Charles Garvice and Miss Ethel Dell and other novelists with high velocity circulations; do not these walk in the garden of prose? They do not, nor are newspapers found there. Those about to become popular abstain from prose as they would the plague. They angle with clichés and dazzle with jargon. They grow rich and famous, but they do not write prose, because, desiring success, and being good business folk, they know that the lovers of prose are so few as to be beneath commercial notice. Some of them couldn’t write prose if they tried, others resist a temptation that does not pay.

* * *

The love of prose is as rare as the art of prose is difficult. There are even more genuine lovers of genuine lovers of genuine poetry; and poetry is rare enough. Note how numerously and on what length critics and interpreters discuss poetry, and even verse, which is not the same thing. For one book on prose there are ten thousand on poetry. Poetic anthologies are ‘as plentiful as tabby cats—in point of fact too many.’ Prose anthologies are rare, and rarely appreciated. Think of the vast circulation attained by Palgrave’s immortal ‘ Golden Treasury of the Best Songs and Lyrical Poems in the English Language ‘—my edition is dated 1894, and up to that date no less that thirty editions had appeared since the first issue, in 1861. In the initial year it was reprinted three times. Has a prose anthology ever achieved a second edition?’

Lintot concludes his mild diatribe by maintaining that:

‘Prose has fewer devotees, but national expression must deteriorate ( is deteriorating) unless those who love the virility of English constantly recall readers and writers to the great tradition and the grand manner of our language. A nation cannot think nor imagine greatly in jargon. We still need high thought and far vision more than ever, but these will be useless to us unless we know how to utter them in strong words and luminous sentences. So in the midst of the babel of undigested and half-visualised demands of this era of discontent, I send forth my suggestion for the period of change: Give us a good Prose Anthology…’

Had he known that at the time when he wrote this a young Etonian named Eric Blair would become the type of prose-writer he might wish to read, perhaps Lintot would not have despaired at the future of English prose. But who from the twentieth century apart from Orwell could now stand with him as a practitioner of lucid, powerful and jargon-free prose? Who else from the twentieth century can compete with the classic prose stylists that Lintot has in mind— such writers as Bacon, Milton, Hazlitt and Lamb? [RR]