Found, in the June 12, 1913 issue of a famous review is this scalding attack on two famous Irish writers.

Found, in the June 12, 1913 issue of a famous review is this scalding attack on two famous Irish writers.

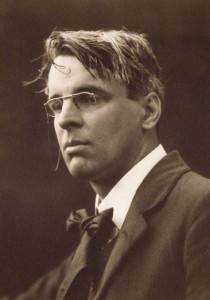

‘In his “Oscar Wilde: a Critical Study “…Mr Ransome remarks that he cannot understand why the Oscar Wilde period (with Mr Yeats, I may add, as its tail-piece) was ever called decadent. Surely, it is either disingenuous or incompetent to fail in such an easy matter. The school was called decadent because it was decadent; and the decadence consisted in the usual feature of decadence, namely the elevation of the part above the whole in value. Pater, I verily believe, never had an idea in his life. In consequence he spent the whole of his energy in concealing the fact in his style. On his style he spent enormous pains as if he knew that he would live by that or nothing. That, I say– the over-attention to style—is decadence. Wilde again was never even a man of letters. Mr Ransome in my opinion utterly fails to present Wilde as he was –an Irish causeur and wit, a born blarney, a talker. In his conversation Wilde was as nearly natural as a self-conscious Irishman in England can possibly be ; that is, he talked to the English as if they were an exotic Frenchman, never by any chance, aiming at the truth, but aiming always at producing in us a pleasant gaping admiration of his cleverness. There are plenty of such Irishmen in England today, only their vogue is past and they no longer surprise us. Too clever for his intellect I called one of them a few weeks ago. Mr Ransome, however, takes Wilde seriously, if critically, as a writer, as a literary man. But as a writer, if you like, Wilde was a poseur. With a pen in his hand he was no longer Wilde but a sort of figure which I can only describe as Turveydrop on paper. He finicked among the words and phrases of the language as if he was playing court to them and was expecting a rebuff from the English genius at any moment. I never saw a page of Wilde that had not “ amateur “ in the vulgar sense written all over it , in vocabulary, in phraseology , and in construction. That also, when the writer is unaware of it, is decadence. It is not mastery of the language, but service under it, as under a mistress. And our language, thank goodness, hates the man who treats it as if it were the Lady of Shallot or Isolda. It is a queen, and its best courtiers are Prime Ministers.

But Mr Yeats, I really think, is more empty of ideas and more tinselled in style than either of his predecessors…Pater and Wilde did occasionally come within reach of manly criticism. In the “Renaissance “of Pater and in the Nietzscheanism of Wilde, the commonsense mind can check their conclusions by comparing them with facts. But Mr Yeats, like the rest of his troop, keeps well in the world of his own invention. He relates nothing but dreams; his people are shadows and his ideas are fancies. How can we test whether what he says is true or not? We have heard it before, but it usually sounds uncommon nonsense. The only means of verifying his veracity lies in his style; and from Mr Yeats’s style I would conclude nothing in favour of his ideas. There is beauty, beauty everywhere, so to speak, but not a drop to drink. A strong page of writing in simple, nervous English nobody can produce for me from Mr Yeats’s writings. His poems? Ah, his poems. Sung or chanted over the fumes from a hookah they sound well. They would do well for a cabin and a peat fire and a mixed company drinking; but in the open air and read to oneself alone, they are too thin to hold the attention from a sparrow dusting itself or a bee on a thistle. For the rest, what has the Irish Literary Society done, what has it produced, what trace has it left on our literature? It has contributed no work even of the second rank of greatness, it has produced no man of any greatness whatever; and finally, its traces, where are they to be found—in our popular versifiers —are those of attenuated imagery, shadowy moods, feeble pathetic rhymes and a carefully selected vocabulary. By the way, Flaubert in France was the master of this species of decadence—its founder practically. Well, Flaubert is no longer read in France. He had nothing to say, and agonised himself to say it…

My idea of an Irish literary society would be a society composed exclusively of men under vows to write for a year about affairs and nothing but affairs.’

What is the name of this periodical, and who was responsible for publishing such a diatribe? The answers are The New Age, and C. R. Orage, a great editor and reformer, indeed the Cobbett of his time, but perhaps, like Cobbett himself, not a great admirer of poetry, and certainly, as demonstrated here, not a lover of the Celtic Twilight. As for Yeats, I cannot find any reference to this review in the Letters, edited by Allan Wade (1954. Perhaps he never read it. [RR]