Remember the moral furore when Fay Weldom included references to Bulgari watches in her novel The Bulgari Connection ? She admitted being paid wheelbarrows of money for this blatant puff. But product placement in fiction is not new. Warreniana , the bestseller published in 1824 by the novelist, parodist and short story writer William Frederick Deacon (1799 – 1845), purports to be a collection of prose and verse by contemporary writers in praise of Warren’s Blacking– the boot polish bottled by the young Charles Dickens in the early 1820s. It is not known whether Deacon received a bung, but as the first edition appears to have been quite large, it is possible that the publishers were financially rewarded by Warren for printing an unusually large number of copies.

Remember the moral furore when Fay Weldom included references to Bulgari watches in her novel The Bulgari Connection ? She admitted being paid wheelbarrows of money for this blatant puff. But product placement in fiction is not new. Warreniana , the bestseller published in 1824 by the novelist, parodist and short story writer William Frederick Deacon (1799 – 1845), purports to be a collection of prose and verse by contemporary writers in praise of Warren’s Blacking– the boot polish bottled by the young Charles Dickens in the early 1820s. It is not known whether Deacon received a bung, but as the first edition appears to have been quite large, it is possible that the publishers were financially rewarded by Warren for printing an unusually large number of copies.

Deacon was primarily a comic writer. Few, if any, serious nineteenth century writers would ever consider augmenting their incomes from writing by referencing a commercial product. One that did, however, was American journalist, novelist and short story writer Charles Stokes Wayne, who under the pseudonym Henry Hazeltine decided to see what would happen if he mentioned the restorative effects of Sanatogen in his Confession of a Neurasthenic (1908).

Although it has now been eliminated from the medical textbooks, from around 1829 until the early twentieth century, neurasthenia was considered to be a genuine physical condition affecting mainly middle class urban workers. Its symptoms of fatigue, lethargy, headache, aching joints and depression were generally put down to overwork and anxiety. Today, many medical professionals recognise the condition as having similarities with ME /CFS.

Here is how ‘Henry Hazeltine’ described his own neurasthenia :

There had been warnings, of course—and yet I had refused to take my condition at all seriously, until suddenly the truth was rushed upon me, and I stood staring at the ghost of my youth and my manhood in the mirror that stretched above my study mantelpiece. My last scintilla of nerve force expended, I was nervously bankrupt’.

Many pages are expended on this ‘true confession ‘of his nervous condition and it is only towards the end of the narrative that the author reveals his secret:

‘Do you know, my dear, exclaimed my wife on her return, that you look positively cheerful this evening? I have not seen you appear so pleased for months. And I do believe you have a better colour. It must do you good for me to go away.

‘ And then I told her…and after that, how we both watched for the added signs and symbols of that promised improvement of which we were now already half assured…

‘The lines of illness and worry grow less and less deep; my hollow cheeks slowly filled ; my eyes lost their sunken dimness. And, coincidently, we noted one change after another, subtly wrought in the way of physical and mental betterment. Among the earliest of these was a day by day gain in activity and energy. A humorous kinsman, ignorant of the effects of nervous depletion, had chaffingly dubbed me ‘The Mollusc’ because of my general disinclination to exert myself. The most trivial undertakings had required, with me, a distinct effort. I would sit hours in one spot, knowing all the while that one thing was required of me, but lacking the will to go about it , and momentarily growing more nervous because I was neglecting it. The overcoming of this will- weakness was one of the earliest indications of improvement”.

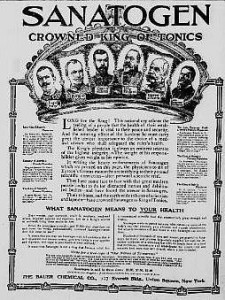

These extracts are taken from a sort of puff for the publication that appeared in The Bookman for November 1913. This revealed that the ‘ Confession’ was written specifically as a tribute to the restorative qualities of the tonic beverage Sanatogen, which according to Hazeltine, ‘ wrought little less than a miracle in me ‘.

The manufacturers of Sanatogen, which claimed to ‘cure ‘ neurasthenia , along with cholera (would you believe? ) must have thanked the day when Hazeltine offered his unsolicited testimonial. So pleased were they, in fact, that they re-issued the work and gave it away to anyone who would ask for it by letter. It is not known how many editions it went through—Abebooks is silent on this matter—or how copies were printed, but doubtless the book made a fortune for the people at Sanatogen. I expect Mr Wayne did well out of it too. [R.M.Healey]