Extracts from The New London Spy (1966)

‘Pubs are what other countries don’t have. In England, country pubs are perhaps nicest of all. After that come the London ones.

Pubs change character as you tipple down from the top of Britain. In the dry areas of Skye you have none at all. In Glasgow they are just drinking shopos. In Carlisle they are cheerless and state controlled.

But in London, there are pubs for all men and for all seasons.’

…if you took the pub away from London, social life in public would almost cease to exist…’

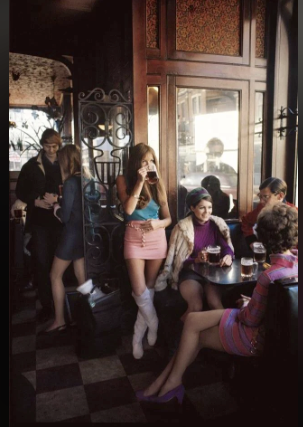

ROUGH PUBS

…London has its quota for the enquiring drinker who likes a barney, or the proximity of physical violence and available women. The most obvious in this category are those around the docks where seamen drink. On of the nicest pubs, though mot kind of place you’d take a maiden aunt, is the Custom House Hotel, known as ‘ the Steps’, Victoria Dock Road. This is a vast sprawling pub, with a raised bar a the back. It provides live music, as well as throwing in a couple of juke boxes. There are other lively pubs nearby, including the Freemasons Tavern an the Railway Tavern, but the Steps take pride of place. You could be in a waterfront bar anywhere in the world, and the atmosphere would be much the same. It is not unusual to see someone almost kicked o death outside, so unless you are on the look-out for a rough-house or know how to ake care of yourself in a fight, avoid getting into an argument.

A better known, and almost as rough, pub is Charlie Brown’s ( actually called the Railway Tavern, but known generally by its nickname, West India Dock Road, which boasts a splendid museum of curiosa from all over the world, collected by one of the landlords. Another guv’nor was stabbed through the glass door, trying to get rid of an argumentative customer. It is also very handy for one of the best Chinese restaurants in London, the Old Friends, almost next door.

Nearer central London is the Admiral Blakeney’s Head, just beyond the Tower in the now rapidly disappearing Cable Street. Cable Street still manages to hit the headlines with the odd murder and the Blakeney’s Head is as virile as ever. Juke boxes, spades, seamen, tarts mingle in a remarkably friendly atmosphere and there are cafes nearby catering for all nationalities. The police still patrol Cable Street in twos.

For those who like their squalor without the atmosphere of violence, there is Dirty Dicks opposite Liverpool Street Station. This has dead cats, cobwebs and sawdust by way of décor. But is in fact a genuine old pub keeping up the tradition of its founder, who amassed a fortune and refused to spend money on clothes. There is a curious collection of postage stamps on which couple have written their names.

In the West End there are a number of well-established rough and ready pubs. Much the famous is the Duke of York’s, Rathbone Street, the beat meeting place in London. This marvellous pub, superbly managed in the face of terrible odds, has a fine and bawdy museum, with a portrait of the late ( and lamented) guvnor, Major Alf Klein, framed by a lavatory seat. Every available inch of the wall and ceiling is taken up with paintings, seaside postcards, ties, sailors’ hat bands and other totally obscure objects. Nearby, in Goodge Street, is the One Tun, known simply as Finch’s, which offers an escape from the beats, which have recently been barred the premises en masse.

Rough pubs in 2025.

A re-reading of the introduction to ‘London Pubs’ suggest to me that it was partly or wholly the work of Hunter ‘Oonter’ Davies, the main reason being that the writer purposely has a sharp dig at the ‘ cheerless and state controlled ‘ pubs of Carlisle, which was Davies’s home town. There is no other reason why anyone else but Davies would select Carlisle as boasting such pubs, though what he means by ‘ state controlled ‘ is not known. The main body of the guide to ‘Rough Pubs’ also presents some problems. For instance, what is meant by ‘ beats’? By 1966 the beatnik movement was long past; perhaps the writer was referring to a dedicated rump of beatniks, just as for thirty or more years after the death of the Punk movement in the UK, men and women dressed like punks, complete with Mohican haircuts were often to be seen in urban areas of Britain. Today, they are far less common.

As for the pubs mentioned by the writer, a number have alas gone for good. The Custom House Hotel, which once flourished on the southern edge of Canning Town, seems to have been one of the many victims of the enthusiastic redevelopment of this area of Dockland that began in the late eighties. Perhaps planners, aware of its sinister reputation for violence, saw an opportunity to replace it with bars and restaurants that the new breed of city types might be willing to patronise. After all, who would relish seeing someone almost kicked to death while you were drinking your pint. The equally dangerous Railway Tavern ( aka Charlie Brown’s) also appears to have disappeared, together with its collection of ‘ curiosa’. By the way, in the language of

book dealers doesn’t curiosa mean pornographic material ? Another casualty seems to have been the Old Friends Chinese restaurant nearby, unless it has changed its name since 1966. This particularly district of the Docklands, fictionalised brilliantly by Thomas Burke in such books as Limehouse Nights , was once teeming with Chinese shop and restaurants, still has a few rather seedy looking joints, but perhaps not ‘ one of the best Chinese restaurants in London’.

Yet another interesting pub that has bit the dust, quite literally, as it was demolished, is the Admiral Blakeney’s Head at the beginning of the once notorious Cable Street. Today this thoroughfare, which saw violent clashes in the mid 30s between the Brown shirts under Oswald Mosely and local communists and anarchists, appears very tame and boring today, unlike the nearby Highway, which keeps its Georgian terraces and magnificent baroque church.

Dirty Dick’s in Bishopsgate is definitely on the tourist map, especially for those on the Jack the Ripper tour. However, according to its online site, which corrects some facts relating to its history, the dead cats and cobwebs referred to have now been cleared away due to health and safety concerns. The New London Spy seems to have quite inaccurate on its early history. ‘Dirty Dick ‘ Bentley was not a publican, but made a lot of money with his hardware business. When his fiancée died he was so distraught that he stopped washing himself and cleaning his home and in 1809 he died as a well known recluse. The owners of the ‘Old Jerusalem’ pub nearby then decided to create a sort of tribute to ‘ Dirty Dick’ by bringing in dead cats, handing part of the pub over to spiders and other creepy crawlies, and duly changing the name of the pub.

Moving west from the city to Fizrovia we find that The Duke of York in Rathbone Street has also survived. Dating from 1791, it looks like a typical late Victorian pub and has always been popular with literary type, including Anthony Burgess, who was inspired by it to write A Clockwork Orange. The allusions to a former guv’nor Major Al Klein are not reproduced in the current description and the ‘ beats ‘ have long fled the scene. However, there remains controversy surrounding the inn sign that depicts the present Duke of York, who long before the Epstein scandal blew up, gave his permission for his portrait to be featured. Today, of course, ‘ Prince ‘ Andrew is no longer Duke of York, so regulars await the fate of the sign.

To be continued…

R.M.Healey

Breweries and pubs were nationalised in WWI in Carlisle and other places near munitions works to keep workers sober. Beer was weakened (was this the origin of “the very fat man/ What waters the workers’ beer”?), buying rounds was banned, food was always available, there were reading and writing rooms and the pubs were run by civil servants who were on a fixed salary and didn’t make or lose money according to how much they sold. The afternoon closure of pubs, which lasted until the 1990s is said to have been introduced because of a shortage of shells at the Battle of Loos in 1915, caused by munitions workers staying in pubs when they were supposed to go back to work.

The scheme continued until the 1970s, but for many years it was the victim of malign neglect before it was privatised.

.