The link between Socialism—or at least, left-leaning tendencies– and bibliophilism has a long and honourable tradition. One thinks of William Hone and Leigh Hunt in the Regency period. Charles Lamb, who wrote warmly of his love for ancient volumes, wrote blistering attacks on the Tory administration of Lord Liverpool in the same era. Later on there was William Morris, a proto- Socialist, who was into fine printing. In our own time the radical Labour leader Michael Foot could be classed as a bibliomaniac. My late uncle, Denis Healey, with a library of around 16,000 books could be placed in the same class. Also, in our own time, David King, the chronicler of Soviet history, had a vast library. And then, two years younger than Foot and a year Denis’ junior, there was Harold Smith. Not quite in the same league as a collector perhaps, but a bibliophile with a collection of over 3,000 volumes of, and certainly one who devoted all his working life to books—initially as a librarian and latterly as a publisher in the tradition of Morris.

The link between Socialism—or at least, left-leaning tendencies– and bibliophilism has a long and honourable tradition. One thinks of William Hone and Leigh Hunt in the Regency period. Charles Lamb, who wrote warmly of his love for ancient volumes, wrote blistering attacks on the Tory administration of Lord Liverpool in the same era. Later on there was William Morris, a proto- Socialist, who was into fine printing. In our own time the radical Labour leader Michael Foot could be classed as a bibliomaniac. My late uncle, Denis Healey, with a library of around 16,000 books could be placed in the same class. Also, in our own time, David King, the chronicler of Soviet history, had a vast library. And then, two years younger than Foot and a year Denis’ junior, there was Harold Smith. Not quite in the same league as a collector perhaps, but a bibliophile with a collection of over 3,000 volumes of, and certainly one who devoted all his working life to books—initially as a librarian and latterly as a publisher in the tradition of Morris.

Smith was born in 1918 in the Hackney Salvation Army Women’s Hospital to a Polish couple who had come to Britain as children. Tragically, Harold’s father died six months after his birth and his mother was left to care both for her son and her war-injured brother, on the proceeds of a sweet shop. After Highbury School and at the outbreak of hostilities Harold served in the army Pay Corps, mainly in South Africa, where he learnt the rudiments of librarianship. On returning to the UK he continued his studies part-time while working on the journal of the Plumbing Trades Union. Following his initial appointment as an assistant at Westminster City Libraries in 1947 he moved to various posts around the country, including one in Manchester, where he became friendly with the artist L. S. Lowry. He ending up back in London as Deputy Borough Librarian at Battersea in 1961. The amalgamation of the old boroughs under the GLC in 1965 saw him as the Deputy Librarian for Wandsworth, which was when his troubles began.

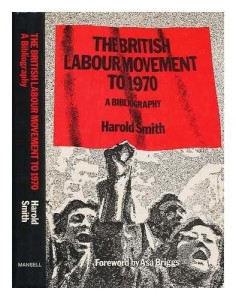

Accounts of his career in this period are vague, but most sources seem to agree that local politics was behind the ‘serious professional conflicts ‘that led to his dismissal in 1975. Nalgo helped him in his appeal to an industrial tribunal and he was eventually found to have been wrongly dismissed. He was reinstated and generously compensated, but refused to return to Wandsworth Libraries, choosing to take early retirement instead. At the age of 57 Smith now had the time he needed to pursue some of the many literary interests he had always had. At various time he was a member of the William Morris Society, the Society for the Protection of Ancient Buildings and the Roehampton Garden Society. A fascination for Labour history was always there. An earlier London University M.A. thesis on The Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge was published by Dalhousie University in 1975. In 1980 he brought out The British Labour Movement to 1970: aBibliography. From his own Nine Elms Press came a series of six monographs on Socialist writers and artists connected with the Arts and Crafts movement– including C.R.Ashbee, William Morris and Walter Crane—all having Morris designs for their covers. These were printed by the prestigious Whittington Press in small editions and they subsequently became coveted collector’s items. His personal collection of material in the field of Socialist history and literature (‘posters, periodicals, pamphlets, books and ephemera’) grew rapidly. Later, he often sold items to scholars and Universities at far less than their market value.

In retirement Smith also began to forge a strong link with the Marx Memorial Library in Clerkenwell. As a volunteer he reorganised the stock and added to it by soliciting copies of new titles for review in the Bulletin, most of these reviews being written by himself. He also promoted the Library by placing its catalogue on the Net and by welcoming researchers from around the world to its resources.

Smith was a lifelong Socialist. Until the invasion of Hungary in 1956 he was a Communist; thereafter he became a member of the Labour Party, but disillusioned by Tony Blair, resigned in 2000. He also cancelled his hitherto lifelong adherence to the Guardiannewspaper, transferring to the Independent,which carried his obituary. As a pacifist he was one of the many who demonstrated in London against the invasion of Iraq.

R.M.H.