Found in a book published by J.R. Tutin, the Hull based reprinter of 17th century literature, a short letter from 1908 to John Haines, a Gloucestershire solicitor and minor poet associated with Ivor Gurney, F.W. Harvey, Edward Thomas and other members of the Dymock Poets group. After discussing various Elizabethan writers Tutin wrote out a fine poem by Ada Elizabeth Smith (1875- 1898) called ‘The Earth Lover’. He had found it in a recent anthology New Songs put together by F Y Bowles – ‘the poem is a real gem in my opinion : yet I’ve not seen it noticed by in any of the reviews of the book.’ A search online reveals little about Ada Elizabeth Smith, a classic poete maudit, except this anonymous (‘J.L.G.’) quite high-flown notice in the London based literary magazine The Academy of December 1898 a week after her untimely death.

Found in a book published by J.R. Tutin, the Hull based reprinter of 17th century literature, a short letter from 1908 to John Haines, a Gloucestershire solicitor and minor poet associated with Ivor Gurney, F.W. Harvey, Edward Thomas and other members of the Dymock Poets group. After discussing various Elizabethan writers Tutin wrote out a fine poem by Ada Elizabeth Smith (1875- 1898) called ‘The Earth Lover’. He had found it in a recent anthology New Songs put together by F Y Bowles – ‘the poem is a real gem in my opinion : yet I’ve not seen it noticed by in any of the reviews of the book.’ A search online reveals little about Ada Elizabeth Smith, a classic poete maudit, except this anonymous (‘J.L.G.’) quite high-flown notice in the London based literary magazine The Academy of December 1898 a week after her untimely death.

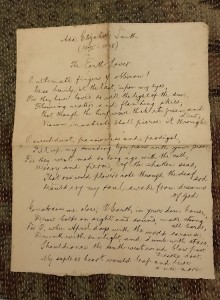

Early Dead. Ada Smith 1875 – 1898 In Memoriam. 17 – 12 – 98

Ada Smith was born in Haltwhistle, a hard featured village from which a bare land runs up to the bleak escarpments that carry the ruined line of the Roman wall. She began early to write verse, and published at 13, having acquired very easily a versification of noticeable grace, smoothness, and cadence. She spent some years abroad, chiefly at Vienna and went about with adventurous and observant audacity. Her idea was that she must not only study life as it met her, but seek it out in the hope of writing novels in the coming time. At this period some of the work found its way into the hands of the present writer. It had too many words and not enough pauses and there was much feigning of the Heinesque. Without being quite able to see what she might arrive at, one felt she must go on.

She returned from Vienna last year with the feeling that she was at last equipped for London, and the great adventure could not be delayed. She attempted London at the age of 22 with a nerve wilful and steady. She did not fail. Verses began to be accepted, and her work matured rapidly. She did typewriting, and it must have been hateful.. Her constitution suddenly began to give way in the summer. A long holiday upon the Northumbrian coast made her better, but not well. She ought not to have gone back to typewriting in the city, but she would and did. A couple of months ago she had to return to the North for the last time quite broken down. Her illness ultimately developed in the gravest way then advanced with frightful rapidity. She died at Newcastle upon Tyne upon the Wednesday night of last week.

Since then have been found among her papers things which show a strange premonition and extremely remarkable development of mind and faculty. None of them is right in every word, but they affront you with snatches of fine things again and again. There are songs of the roadside, of the sea, of March; there are craving and foreboding songs, many sad, but few unhappy. Some of them are a brave- nay, a gay – wooing with death. This is from stanzas which must have been among the last and are significantly headed Finale

“Little you dream, O eager and delicate brain,

O delicate heart and deep,

That life which drove you mad with creative pain

in the end would heap

Pansies above you…”

This is the opening of March

“O sick for March month am I

Sick for the free, fresh weather,

Bare boughs tossed on a sapphire sky

Brown brooks singing together,

O sick for March month am I.”

…[One poem that should be shown in full]

THE EARTH LOVER

Press heavily at the last upon my eyes.

For they have loved so well the light of the sun,

Flowing waters and flashing skies,

That though the turf weave thick it’s green and dew,

Vision insatiate shall pierce it through.

Fill up my sounding tympans with your peace,

For they went mad so long ago with the call,

Weary and fierce, of the shaken seas,

That one wild plover’’ss note through the deaf sod

Would cry my soul away from dreams of God!

Draw bolts on sight and sound, make strong all bars;

For O, when April days with the world carouse,

Drun with sunlight and dumb with stars,

Should once the south-west wind blow past deaths door,

My sapless heart would leap and live once more!”

One did not anticipate at all that Ada Smith would die early. One had been so used to think of what she might have been, had counted time so confidently for her, that her death, removing but what she was, could scarcely change the habit of speculating upon her future.

Ada Smith would have liked to be buried out on Blanchland Common, since that could not be, she wished her grave to be in the old silent churchyard of St John Lee. The churchyard of St John Lee is a grave little solitude deeply withdrawn upon a hill where the steeple of the small old church just points above the trees. Far below the time draws the Tyne draws the cold glimpses of its curves through the vista of leafless trunks and branches. Away over the valley the opposite hills move across the view with long slow modulations, a subtle rhythm. They seem at once close and shadowy, explicit and mysterious, gradual and absolute. You know these hills. They come upon you unawares and you shall be subject to them always. You ache with the peacefulness; you are exasperated by the extreme simplicity: their moderation makes you despair; their spell is unreasonable, inexorable, and so you also would like to be buried among them. The road winds upwards from Tyne Bridge between high banks and under an antique guard of vast beeches, and the wall near the churchyard gate is padded with long mosses.

Church of St John Lee, Northumberland

The day she was buried – last Saturday – was just such a day as would have made her laugh and walk 20 miles with you. She was free of the Northern moors from childhood, unable to endure being much alone with them and the joy of the solitude that is accepted, not compelled. Her stanzas were a little morbid from the first, not with blackness, but with excessive desire for action. It was the discontent of a vitality craving for scope and fretting against restriction.Looking along three shelves of latter-day lyrics, one cannot see anything with quite the same promise of a nature poet that Ada Smith gave. The Heinesque note, which was her form of the imitative, would not have detained her long. Her most vivid and vital verses were like things plucked up out of soft earth with the moist soil still clinging to their roots. J.L.G.

Reminds one slightly of Dowson. Ada may not have read her contemporaries iike Browning or Swinburne. If she had there may have been less ‘O’s” and ‘eths’. The March fragment is very fine.

I am delighted to find this account of the life of Ada Smith, because I only ‘discovered’ her today, because of finding her poem ‘In City Streets,’ anthologised in ‘Poems of Today’ (London: Published for the English Association by Sidgwick and Jackson, Ltd., 1944). The first edition was, however, 1915, and the anthology went through numerous re-printings. No editor is credited, but the Prefatory Note begins: ‘This book has been compiled in order that boys and girls, already familiar with the great classics of the English speech, may also know something of the newer poetry of their own day’ (1915). I had had this little collection on my shelves for over 30 years but had only now begun to study it. There, among the expected Georgians was the one Ada Smith poem – and a brief biographical note, possibly derived from the passage quoted above.

John Crompton.