Everyone knows about the General Strike of 1926. It paralysed the nation for nine days and the serious damage it inflicted on the relations between employers and employees was never quite repaired. However, just a few months before the General Strike another strike took place that largely seems to have been written out of labour movement history. The Internet has little or anything to say about it and it doesn’t seem to have troubled historians. It was the Book Trade Strike of December 1925.

Everyone knows about the General Strike of 1926. It paralysed the nation for nine days and the serious damage it inflicted on the relations between employers and employees was never quite repaired. However, just a few months before the General Strike another strike took place that largely seems to have been written out of labour movement history. The Internet has little or anything to say about it and it doesn’t seem to have troubled historians. It was the Book Trade Strike of December 1925.

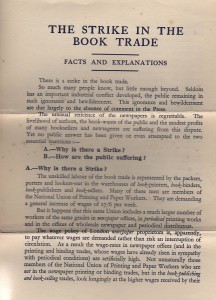

We at Jot HQ were unaware of the strike until a four page flier was discovered among a pile of papers. Entitled ‘The Strike in the Book Trade ‘and issued by the Book Trade Employers’ Federation on December 10th1925, it outlines the reasons for the strike, who were involved in it, the effects of it on the public, and possible remedies. The main arguments put forward by the employers’ Federation against the strike focussed on the privileged position of those unskilled workers in the book trade who were at the centre of the dispute—the ‘ packers, porters and lookers-out ‘—compared with other unskilled employees doing similar work in other branches of industry in London.

The figures supplied by the Federation to support their case are themselves revealing. Packers in the book trade were indeed paid better and worked fewer hours than the majority of their peers elsewhere in the metropolis, as this table of payment demonstrates:

Wage Age Hours

Packers in Drug and Chemical Trade 58/- 21 48

Packers in Co-operative Societies 60/- 24 48

Packers for London Employers’ 62/- 24 48

Association

Packers in Furniture Trade 62/1 21 47

Packers for Wholesale Textile Association 63/- 25 44

Packers in Cloth Trade 64/8 21 48

Packers for Export 64/8 21 48

Packers in Book Trade 65/- 21 44

The Federation announced that these book trade packers were demanding a rise of 17/6 a week and suggested that this was because workers in the newspaper industry who were members of the same National Union of Printing and Paper Workers were envious of their higher pay. The Federation admitted that this was because newspaper proprietors, who relied on advertisingfor their main income, could be held to ransom by workers and chose to accede to demands from them rather than interrupt the flow of newspaper production. In contrast, publishers relied entirelyon the sale of books for their income. If packers were paid more the price of books in shops would increase and the demand for books from the public and libraries alike would inevitably fall off.

One must admit that the pay rise of around 22% demanded by the elite among manual workers seems decidedly steep today, but one must remember that the 1920s was the highpoint, not only of the subscription library movement, but book publishing in general. After the paper shortage that resulted from the First World War publishers were able to benefit enormously from the revival in reading that came with increased prosperity. Nor did the cultural output of the BBC, which had only been going for three years in 1925, prove to be a rival to the publishing trade. In any case, many people did not own wireless receivers at this time. Book packers doubtless felt that publishers, despite their protestations, could bear the burden of a wage hike.

Who won this strike? We at Jot HQ do not know, but perhaps others in the Jottosphere are better informed. We welcome elucidation. [R.M.Healey]