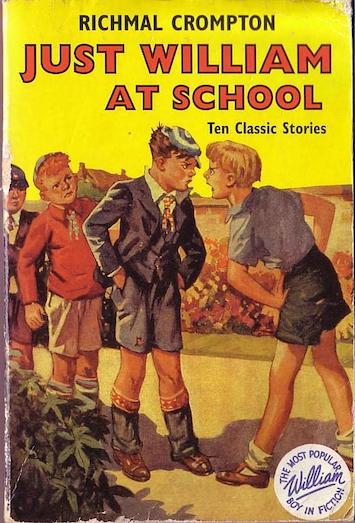

Today, when fully formed adults from around the world queue patiently at the portal to Platform 9 ¾ at King’s Cross Station to have their photograph taken beside the Harry Potter luggage trolley, it’s worth reading another and better children’s writer, the one-time Classics teacher and creator of William, Richmal Crompton, as she explains in an article in the October 1952 issue of The Writer, how she began her career as a writer for adults.

‘I submitted the first one to a women’s magazine and the editor, accepting it, asked for another story about children. I remember that I racked my brains, trying to invent a different set of children from the ones I had already used, and it was with a feeling of guilt and inadequacy that I finally fell back again on the children of the first story. Asked for a third story about children, I wrestled once more with the temptation to use the same set of children, succumbing to it finally with the same sense of guilt. When I had written the fifth story I said to myself: “This must stop. You must find a completely different set of children for the next story.” But somehow I didn’t and gradually the ‘William’ books evolved. They were still, however, regarded as books for adult reading, and I think it was not till the last war that they found their way from the general shelves to the children’s department in the bookshops. And even now I receive letters from adult—even elderly –readers…

…if you are writing about children for children, you must be able to see the world around you as a child sees it. To “ write down” for children is an insult that a child is quick to perceive and resent. Children enjoy assimilating new facts and ideas, but only if the writer is willing to rediscover these facts and ideas with the children, not if he hands out information from the heights of adult superiority. I think the fact that the ‘William’ stories wer4e originally with no eye on a child-reading public has helped to make them popular with children…The plots are not specially devised for children, but I think that if there’s anything I the story that children don’t understand they just don’t worry about it. Children, too, seem to like a series of stories dealing with the same character—especially if it’s a character with which the normal child can identify itself…

In those early days I saw myself as a budding novelist and wrote the William stories —rather carelessly and hurriedly—as pot-boilers. The history of the pot-boiler, by the way, is an interesting one. Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes stories, Hans Andersen’s fairy tales, Stevenson’s Treasure Island were all written as pot-boilers…Stevenson would have been surprised to know that after his death the story that people connected most readily with his name would be Treasure Island…

It is an excellent plan when writing a series of stories round a central character, to keep a careful record of plots, relatives, friends, foes, places and people. I must in honesty admit that, so haphazard was the growth of the William books, I only started this practice a year or two ago; and the earlier books are full of discrepancies that more methodical-minded readers occasionally point out to me . But I am sure that the keeping of a card index gives continuity and human interest to the stories and enables one to use again characters who would have vanished from one’s mind unless firmly pinned down between the leaves of a card index..

The school story, too, is always popular and the girls’ school story classic remains to be written. We have nothing to set against Tom Brown’s Schooldays or even The Fifth Form at St Dominic’s ! In this connection I should like to point out that the new Grammar School milieu , created by the recent Education Act, is an unexplored ( or only partially explored) field, full of rich material. Most of the existing school stories have as their setting the old public or private school, and there should be a large public for schools dealing with what is sometimes called the ‘ new education’ and the home life of the young scholars who benefit—or fail to benefit—by it…

…I don’t think there is any hard line of demarcation between writing for children and writing for adults (except, of course, in the case of very tiny children). A child and an adult dwell side by side in most of us. The normal child has a keener insight into the adult world than we realise, and the normal adult is nearer his childhood than he would admit. So that, if I were asked to give advice to a writer of children’s stories, I should say: find some theme that satisfies both the child and the adult in you, focus the child’s eye on it, then—go ahead and enjoy yourself .

Richmal Crompton was born in 1890. From 1922, when the first William book appeared, until 1952, when this article was published, she wrote 28 William books. Another 11 appeared between 1952 and 1970. In addition, Crompton published 41 novels for adults and 9 collections of short stories. She died in 1969.

[R. M. Healey]