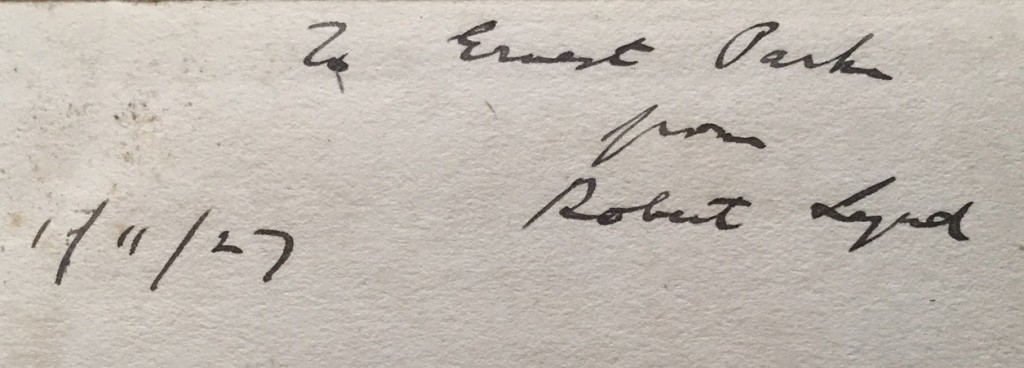

Found in the vast Jimmy Kanga* collection a signed presentation copy of Robert Lynd's The Sporting Life and Other Trifles. Lynd (1879-1949) is a rather forgotten Irish born essayist. His Gaelic name was Roibéard Ó Floinn, and he wrote essays, often humorous, occasionally under the name 'Y.Y.' (wise.) Lynd settled in Hampstead, in Keats Grove near the John Keats house. He and his wife Sylvia Lynd were well known as literary hosts (Hugh Walpole, Priestley etc.,) Irish guests included James Joyce and James Stephens. The publisher Victor Gollancz reports Joyce intoned Anna Livia Plurabelle there to his own piano accompaniment. Hampstead is the now the haunt of oligarchs and wealthy media types. A customer recalls that even into the 1970s, when he lived in Frognal, cabs were reluctant to venture that far from the West End. Now it is probably a favoured destination…Lynd writes:

HAMPSTEADOPHOBIA is a disease common among taxi-drivers. The symptoms are practically unmistakable, though to a careless eye somewhat resembling those of apoplexy. At mention of the word " Hampstead" the driver affected gives a start, and stares at you with a look of the utmost horror. Slowly the blood begins to mount to his head, swelling first his neck and then distorting his features to twice their natural size. His veins stand out on his temples like bunches of purple grapes. His eyes bulge and blaze in their sockets. At first, for just a fraction of a second, the power of speech deserts him, and one realises that he is struggling for utterance only because of the slight foam that has formed on his lips.

|

| Hampstead Heath by Gerald Ososki (thanks A.T.G.) |

As one catches the first words of his returning speech, it is borne in upon one that he is praying. One cannot make out from the language of his prayers whether he is a Christian or a devil worshipper or a plain heathen. It is clear that he holds strong religious views of some kind, but he seems to be as promiscuous in his worship as an ancient Greek. What is still more curious, he seems to pray again and again and again for blindness.

I have often been puzzled as to the explanation of this. Is there some legend among taxi-drivers about a loathsome monster that lurks in the deeps of the Leg of Mutton Pond, and the mere sight of which causes madness in men of this particular calling? Or is their terror the result of some old story of a taxi-driver who once took a fare to Hamp stead late at night and was never heard of again? Or is it guilty conscience that is at the back of it all? It may, for all I know, be recorded somewhere in history that the taxi-drivers once did a great wrong to the people of Hampstead " perhaps there was an invasion and an attempt to destroy the steep and beautiful hill " and are afraid to go there because of the vengeance of the inhabitants.

It is certainly a remarkable fact that while men of all other professions visit Hampstead in perfect security as a holiday resort, the taxi-drivers alone shrink from it as though it were a suburb of Gehenna. Do they expect the Spaniard to leap out on them with a knife, or the Bull to plunge forth snorting and fire-breathing from behind the Bush? No taxi-driver has ever told. I doubt whether anyone could extract the truth but a psycho-analyst.

Something, however, ought to be done. I cannot believe that among taxi-drivers the disease of Hampsteadophobia is inevitable. I am confident that taxi-drivers could be trained in such a way as to make them as little afraid of the name of Hampstead as a horse is nowadays of a steamroller.

They might be accustomed to the sound of the dreaded name little by little. It would take a year, probably, to teach them not to start at the first whisper of the letter " H." During the second year they could proceed from " Ha " to " Ham " and, with luck, even to " Hamp." By the end of the third year, if a man stealing up behind one of them in goloshes and barking into the right ear the complete word " Hampstead " " if they were able to endure this without the quiver of ari eyelid or any invocation of supernatural aid, they might then be regarded as proof against the disease, and be given their licences as taxi-drivers.

If something of this kind is not done, the disease will inevitably spread, and the taxi-drivers at railway stations will have to be put into muzzles.

* Jimmy Kanga, who passed away on 9th September 2012, was a gentle, kind, decent, diffident, extremely polite and—I would say—sensitive man. Although in the last few years, he had been less active due to health problems, his arrival, usually late in the day and carrying at least two carrier bags, one with his bank statements in—so he could work out to the last pound how much he could afford to spend—was a familiar, and welcome sight at the London book fairs.

He was well known to most booksellers in London, and to catalogue dealers around the country. He was an unusual collector, not so concerned about condition or edition, or even whether he already had the book. Towards the end of a 45-year book-collecting career, when he couldn’t fit any more books into his modest house in Southall, he left them dotted around all the booksellers he visited in London: I sometimes wondered whether I was the only bookseller in London with boxes of Jimmy’s books in the attic, or whether I was the only bookseller to be called at all hours throughout the day with long lists of books to be obtained. Such was his passion for books that the calls did not stop when Jimmy was in hospital. From his hospital bed Jimmy would call through to ask for more titles of books, still assuring me that he would come and pick them up. On this latter point, perhaps, we both knew that he would not.

His interest was mainly English, European, American and, unusually, New Zealand and Canadian Literature, especially from the nineteenth to the early twentieth century. He didn’t seem to have any interest in Modernism. There were over 20,000 volumes (including many duplicates) in his home when he died. Often, if he couldn’t actually find a title, he would buy another. His knowledge of the greater and lesser-known poets and novelists of Spain, Italy, France and Belgium, Scandinavia was very extensive. Among British writers he collected Walter de la Mare and Alfred Noyes, with whose families he had corresponded. He collected Chesterton, Quiller-Couch, Edward Thomas, and novelists such as Dickens Gissing and Hardy.

Without doubt, Jimmy was an unusual, and seemingly eccentric soul: he had little interest in clothes, and neither was he much concerned about money or the material or commercial worlds, except insofar as they applied to buying books. Certainly, his books and reading came a long way ahead of eating in his priorities. However, although it would be true to say that he was rather shy and solitary, and in many ways didn’t ‘fit in’, it would be a mistake to dismiss him as a ‘loner’ or ‘misfit’. Much of the companionship and affection in Jimmy’s life came through the books he bought and the people he came into contact with when acquiring them. But it should be remembered that for 35 years Jimmy worked as an examiner in the Estate Duty Office, a branch of H.M. Customs and Excise. He was held in esteem and affection by his colleagues there, three of whom attended his funeral. When his office relocated to Nottingham in 1995, Jimmy took early retirement, and from then on his book collecting became ever more consuming.

Born Jamshed Manic Kanga in Bombay 1941, Jimmy’s family background was Parsee, but he was Catholic. Both his parents were very interested in western classical music, and his mother was a gifted concert pianist. Many of the authors he liked were Catholic, and he attended St.Anselm’s Church in Southhall, where his funeral took place. He came to England in 1958, attended university, took the Civil Service exam and a diploma in law, and joined HM Cusoms and Excise. After his parents passed way he never went back to India. He had no family in England but, in later years, was looked after by a local Sikh family.

All in all, we won’t see again the like of his beautifully spoken English, his almost Victorian politeness, his wide love and knowledge of literature, and his passion for collecting books. [David Tobin- for which much thanks.]

We (Any Amount of Books) used to have quite a bit about Jimmy on our site and it could be retrieved via the Wayback Machine but currently we have this:

[The} Jimmy Kanga (bless his name) collection ...includes Edwardian fiction, Catholicism, ChesterBelloc, de la Mare, Barry Pain, Viola Meynell, Julian Green, Knox, Gosse, Vernon Lee, Forrest Reid, Mary Webb, Fiona Macleod, John Buchan, J K Huysmans, A.E., Edward Thomas, Michael Field, Alfred Noyes and a load of European lit in English. Jimmy was probably London's most celebrated & loved book collector of the late 20th century. He can even be found (along with Martin Stone) as a character in Iain Sinclair's White Chappell, Scarlett Tracings (as J. Leper-Klamm 'unravelled pharaoh').