If the baby-eating Bishop of Bath and Wells out of Blackadder was a grotesque fiction—the reign , centuries later, of Henry Philpotts, one of whose letters is reproduced here, is something we might associate more with tyrannous Tudor bishops than with their supposedly anodyne Victorian successors.

Philpotts (1778 - 1869 ) was Bishop of Exeter between 1830 and 1869—the longest episcopacy since the 14th century. One of 23 children of an innkeeper, he is said to have been elected a scholar of Corpus Christi College, Oxford, at just 13, and graduated five years later. In 1802 he was ordained and by 1809 had held four livings, cementing in that time a lucrative connection with the diocese of Durham, where he became a Canon. Some idea of his aggrandising nature may be gained by the fact that after his election to the bishopric of Exeter in 1830 he asked that he be allowed to retain his former living of Stanhope, Co Durham which, due to the value of church land in such coal-rich territory, was then worth the enormous sum of £4,000 p.a.—amazingly £1,000 more than his new bishopric. This happy arrangement was refused, but Philpotts was permitted to keep a residentiary canonry at Durham, which brought with it a similar sum to that which he had lost, and which he retained until his death. The distance between Durham and Exeter is around 350 miles, which raises the question as to how often he, as Bishop of Exeter, was able to satisfactorily fulfil his obligations as a residentiary canon at Durham.

In 2006 it was claimed at the General Synod that in 1833 Philpotts had received almost £13,000 (around £1m today) in compensation under the terms of the Slavery Abolition Act for the loss of slaves that had been emancipated. The MP Chris Bryant repeated the allegation in the Commons, but it was subsequently proved that the slaves were owned by the Earl of Dudley and that the compensation was paid to the Bishop and three others while acting as trustees and executors. It has been contended that as an executor Philpotts would not have been entitled to any share of Dudley’s fortune, but it has also been suggested that his slave compensation money was used to build the large Italianate-style sea-side palace in 25 acres at Torquay, which replaced his former home by the cathedral in Exeter and which when completed in 1841, looked more suited to a Midlands industrialist than a man of the cloth. This he named Bishopstowe.

Phillpotts was a deep-dyed Tory reactionary who was generally disliked both locally and in the wider world. Though a reformer of local ecclesiastical abuses, in the Lords, while other bishops were promoting political and social reform, Philpotts opposed both Catholic Emancipation and parliamentary reform and was an ardent Tractarian. His Whig opponent, Lord Melbourne, called him that ‘devil of a bishop ‘and he even alienated a former Tory friend, the normally tolerant Sydney Smith. In debate he could be eloquent and learned, but his terrier-like disposition, lack of tact, liking for polemic, and above all, a dogged refusal to adapt his own conservative principles to the political mood of the times, are now recognised as serious faults in someone of his influence in the Church.

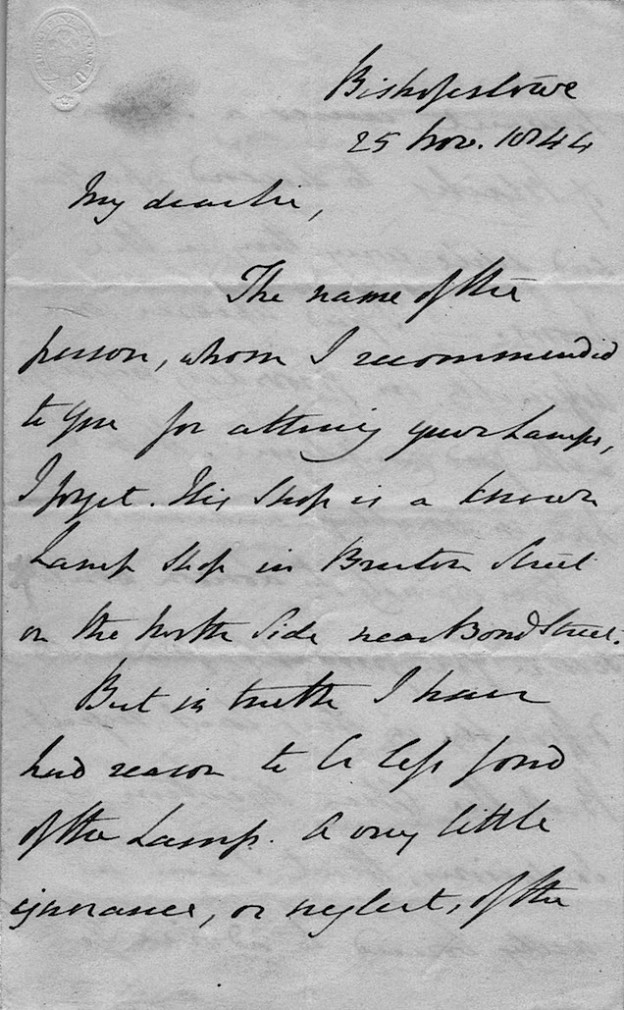

The letter shown here is addressed to his friend, the well known Tory writer and MP John Wilson Croker and is dated 25 November 1844. In it Philpotts, writing from Bishopstowe, discusses the merits of modern domestic lamps. He recommends a good lamp shop in the West End, but warns him that if he buys a lamp like his he risks precipitating particles of lamp black all over his house:

‘ A very little ignorance , or neglect of the Servant causes a shower of Blacks to descend upon you and defile every thing in the Room…I suffered so terribly one day from the shower of Black snow , which covered every book & paper in my room , that I regretted having had to do with the lamp. Yet it is very tempting—for when all goes right, the light is exquisite…’

Connoisseurs of Victorian architecture now have a chance of sampling the opulence once enjoyed by Philpotts, as his former home now forms part of The Palace Hotel, one of Torquay’s finest. [R.M.Healey]

There were several court cases after the death of Lord Dudley, all related to the authenticity of the will. In a codicil letter attached to the will, the Bishop is bequeathed £2000; and othe trustees were awarded large sums of money. There was much speculation as to whether or not the will had been forged.

Also attached to the will are two affidavits by John Benbow ( solicitor) and Henry Money Wainwright (clerk to John Benbow) dated over a year after Dudleys death attesting that the will and codicil letter were written by Lord Dudley. Wainwright scribed the will and was also a witness to the will. One theory is that Wainwright forged Lord Dudleys handwriting. Lord Dudley was suffering with severe mental health issues during the course of his life and spent his last days under medical care due to his poor mental health.