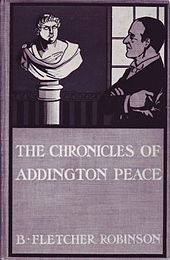

The title page of the 1902 first edition bears just one name—Arthur Conan Doyle. And if you believe Conan Doyle’s son Adrian and just about every Sherlockian you’ll ever meet, only one man wrote the famous detective story. But in a newspaper cutting from the Daily Express dated March 16 1959 in the Haining Archive, the journalist Peter Evans tells how he met an 88 year old man from Dartmoor who swears that another writer of detective stories, Bertram Fletcher Robinson (1870 – 1907), the author of The Chronicles of Addington Peace (1905) contributed some material to the book. That man was Harry Baskerville and he had worked as the coachman to Fletcher Robinson’s father.

According to most accounts, Fletcher Robinson’s only contribution was to tell his friend Conan Doyle about the West Country legend of a ghostly hound and to borrow the name of the family coachman for Sir Henry Baskerville. Indeed, the octogenarian even showed Evans the inscribed first edition of the book in which Fletcher Robinson acknowledges as much. But Baskerville claimed much more for his employer’s son:

‘Doyle didn’t write the story himself. A lot of the story was written by Fletcher Robinson. But he never got the credit he deserved. They wrote it together at Park Hill, over at Ippleden. I know, because I was there.

According to Baskerville, long before Conan Doyle arrived at Park Hill, Fletcher Robinson had confided:

“Harry, I’m going to write a story about the moor and I would like to use your name”.

Baskerville then continued:

“Shortly after his return from the Boer War, Bertie (Robinson) told me to meet Mr Doyle at the station. He said they were going to work on the story he had told me about.

“Doyle stayed for eight days and nights. I had to drive him and Bertie about the moors. And I used to watch them in the old billiards room in the old house, sometimes they stayed long into the night, writing and talking together.

Then Doyle left and Bertie said to me:’ Well, Harry, we’ve finished that book I was telling you about. The one we’re going to name after you’ ”.

But when Evans phoned Doyle’s son Adrian, he denied that Fletcher Robinson had collaborated in the book and that Doyle had stayed with him at Park Hill to work on the project. According to Adrian, the extent of Fletcher Robinson’s contribution, which Conan Doyle had acknowledged in the preface to the book, was merely to have told the latter of the West country legend.

When Evans presented this response to Baskerville, the old man repeated his assertion.

“There was never such a legend. It was a story that Bertie had invented and helped to write. I don’t know why he didn’t get more credit. It didn’t seem to worry him, though “.

A number of points are raised by this interview with Baskerville. The main one concerns interpretation. Baskerville was not a literary man and may have mistaken long chats into the night, and even what appeared to be ‘writing ‘, with literary production. The fact that Doyle was handed written down details of the legend by Fletcher Robinson does not mean that what was published as The Hound of the Baskervilles contained sizeable literary contributions by him. It also does not follow that because Fletcher Robinson told Baskerville in advance that he intended to write a story about the moor, that Fletcher Robinson eventually carried out this project in conjunction with Conan Doyle.

Of course it is entirely possible that Fletcher Robinson did hand over to Doyle in the billiard room large chunks of his own writing—he was, after all, a successful writer of detective stories himself. If so, it is likely that he and Doyle discussed this writing in long talks together. It is also possible, though highly unlikely, that Doyle promised to incorporate, without intervention by him, this literary material into the book and that he eventually reneged on this promise, for whatever reason. The fact that Fletcher Robinson seemed unconcerned that Conan Doyle had not given him more credit would tend to suggest that he did not value very highly his own contributions to the novel. After all, most authors who have spent time and intellectual energy on a piece of writing would expect both significant credit for their work and a cut of any fees generated by it.

The denouement of this story raises even more serious issues. In 1907, five years after the publication of The Hound of the Baskervilles, Fletcher Robinson died at the early age of 35 of an enteric disease following a spell in Egypt. He had travelled there to investigate the curse of a mummy, but had fallen ill. Conan Doyle had previously warned him not to tempt fate by involving himself in such a perilous search, but this advice had been ignored.

Recently Rodger Garrick-Steele in his House of the Baskervilles argued that Fletcher Robinson did not die of a disease, but was over-dosed with laudanum by his wife Gladys, who was having an affair with Conan Doyle, who aided and abetted the crime. Conan Doyle also feared that eventually the truth regarding his friend’s significant role in the creation of The Hound of the Baskervilles would be revealed and that this revelation might damage his own reputation as an author. With little or no evidence to back up his claim, Garrick-Steele applied to have Fletcher Robinson’s body exhumed, but in 2008 this application was rejected by the Exeter Diocese Consistory Court.

Your Jotter has not read the book, but on the face of it such a theory seems improbable, to say the least. Discounting the objection put forward by one Sherlockian that Conan Doyle was not ‘the poisoning type of person ‘ ( there were plenty of doctors who killed with poison for various reasons), we can instead argue that the author was much more intelligent that the average physician of his day and moreover that such Sherlock Holmes stories as ‘The Devil’s Claw’ and ‘The Dying Detective’ (particularly the latter) demonstrate that Conan Doyle was familiar with a number of subtle ways in which someone could be killed by poison. Nevertheless, did Conan Doyle have a strong motive for doing away with Fletcher Robinson, particularly as the latter, according to the coachman, seemed unconcerned by the lack of credit accorded to him for his contributions to The Hound of the Baskervilles? Of course, we do not know what passed between the two men in the five years that had elapsed since its publication, during which time the fame ( and wealth) of Conan Doyle had increased, in contrast to that of Fletcher Robinson; but murder seems a drastic solution to any problem of authorship that may have surfaced at this time.

Having said that, there are a few examples of eminent people—scientists, academics, and authors — who have murdered, perhaps with less provocation… [R.M.Healey]