The contribution of W.O.G. Lofts ( 1923 – 1997) to the history of boys’ fiction in the British periodical press is immense. ‘Bill’ Lofts, a mechanical engineer by training, but a fact-collector by inclination (why did he never enter BBC’s Mastermind ?), was also interested in detective stories. Sexton Blake and Sherlock Holmes were two creations on which his skills as an astonishingly assiduous researcher were exercised to great effect. Years spent among the riches of the British Museum Periodical Library at Colindale on projects which probably no-one else had either the energy or commitment to pursue produced what turned out to be invaluable guides to the more obscure purlieus of popular literature. One such study was The Adventures of Herlock Sholmes: a History and Bibliography, a pamphlet co-written in 1976 with the owner of the Dispatch Box Press, Jon Lellenberg, an expert in the history of Sherlock Holmes in parody and pastiche.

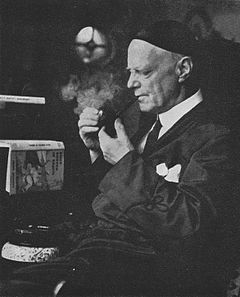

According to Lofts and Lellenberg, the story of the Herlock Sholmes parodies was also the story of their creator, Charles Hamilton (above) the most prolific writer in the English language, who as the mainstay of Amalgamated Press, is estimated to have written around 72 million words in his whole career , the equivalent of a thousand full-length novels. Using the pen name ‘Peter Todd’, which was the name of a pupil at Greyfriars School, which Hamilton had dreamed up for The Magnet, Hamilton made Todd a contributor of Sherlock Holmes parodies to The Greyfriars Herald, the school’s own newspaper, which Amalgamated Press brought out as a separate publication.

The first Herlock Sholmes story, ‘The Adventure of the Diamond Pins’, appeared in the first issue of The Greyfriars Herald, in November 20th, 1915. At 1,500 words, it was ‘not bad at all ‘in the opinion of Lofts and Lellenberg, who continued:

By the fourth story the series began to pick up and get into stride, and Hamilton established a pattern for the other parodies to follow. He knew his Conan Doyle well, of course, and occasionally would base a parody upon a particular canonical story---a title like ‘ The Freckled Hand ‘ or ‘The Yellow Phiz ‘ needs little explanation. But Hamilton had further ideas for the character and stories as well. Herlock Sholmes also served as versatile vehicle for some clever satire, much of which was probably lost upon the schoolboys who comprised the greater part of his audience. Hamilton had a breezy, punning style as a parodist, a zany gift for appealingly ludicrous names, and a sharp eye out for the commonplace annoyances of everyday life that could be turned into material for burlesque. He focussed his ire upon current events and popular styles and fads, gleefully blistering such bizarre creatures as Americans, pettifogging politicians, and especially government bureaucrats. At first, wartime topics like shortages, food rationing, and special government powers and red tape were among his favourite targets, but after the war he was never at a loss for others. For him, cubism in peacetime art was so unpalatable as American tinned meat had been in wartime, and the pompous self-importance of a prominent opera singer was as much fun to deflate as an air raid warden’s had been. Hamilton was a man of no uncertain views, and the Herlock Sholmes parodies gave him the opportunity to vent his opinions and tastes. What mattered most was the barb, and from the beginning he kept it honed.

After just eighteen issues, however, the Greyfriars Herald folded, a victim of wartime paper shortages. Each issue had contained a complete Herlock Sholmes story, but though Hamilton had several stories left over when the plug was pulled, he didn’t publish them until December 1916, when The Magnet featured ‘ Herlock Sholmes’s Christmas Case’. Thereafter, five further stories appeared in this magazine but in the following year they began to be shared between The Magnet and The Gem. After ‘The Case of the missing MS ‘ was published in The Magnet for November 30 1918 the series languished until it was revived in a new-look Herald on June 12 1920 with Todd’s ‘The Missing Cricketer’. Thirty-two further stories followed in the same paper, after which they began to feature in The Penny Popular, The Magnet and The Popular.

Although Hamilton proudly claimed to have written all the ‘Peter Todd’ Herlock Sholmes stories, contemporaries at Amalgamated Press, as well as modern authorities, including Lofts and Lellenberg, doubt that he did. One name put forward as a minor contributor to the series was G.R.Samways, himself a gifted parodist at Amalgamated Press before he left to become a freelance. Two other candidates are Stanton Hope and William L. Catchpole. But it is incontestable that the final parodies that appeared between October 1939 and January 1940 under the pen names ‘Sheerluck Homes’ and ‘Sheerluck Jones’ were not the work of Hamilton, but of the ‘ less talented ‘ Hector Hutt. [R.M.Healey]