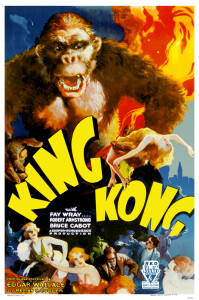

Found– a one page ‘flyer’ put out by a surrealist group in Leeds for a season of ‘Surrealists go to the Cinema’ held at Bradford cinemas in November 1994. It reprints a 1934 review of the 1933 King Kong directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack. The review was by Jean Ferry a French writer and later ‘pataphysician’ who saw it as a poetic film ‘heavy with oneiric power’ but, curiously, he does not attribute this to the makers of the film… It reads:

Found– a one page ‘flyer’ put out by a surrealist group in Leeds for a season of ‘Surrealists go to the Cinema’ held at Bradford cinemas in November 1994. It reprints a 1934 review of the 1933 King Kong directed by Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack. The review was by Jean Ferry a French writer and later ‘pataphysician’ who saw it as a poetic film ‘heavy with oneiric power’ but, curiously, he does not attribute this to the makers of the film… It reads:

I had so definitely given up the idea of seeing a poetic film that, beside any attempt at criticism. I cannot help reporting the appearance of that rare phenomenon, greeted as you would expect by howls of derision and contempt. I hasten to add that what gives this film value in my eyes is not at all the work of the producers and directors (they aimed only at a grandiose fairground attraction), but flows naturally from the involuntary liberation of elements in themselves heavy with oneiric power, with strangeness and with the horrible. … It appears, finally, that the tallest King Kong, for there were many of them, as you may have guessed, was but a metre high. But you see we knew it already. And this is why I think the inept laughter of the public is only a defence mechanism to force itself to think that this is only a mechanical toy and, having succeeded in this, to escape the feeling if unheimlich, of disquieting strangeness, that we cherish and cultivate, for our part, so carefully, and which nothing brings to life as readily, and rightly so, as being in the company of automata. I think that the film would be no less moving, no less frightening, if it was not about a supposedly living beast but an automaton of the same height making the same movements. In any case, whether the monster is real or false, the terror he provokes takes on no less of a frenzied and convulsive character through its very impossibility. Suppose that you, sitting on the Metro suddenly see his head appear over the trees on the Boulevard Barbes, would you ask yourself if this is machine before feeling frightened?

To sum up, through the absurdity of its treatment (an inept script with numerous incoherent details), its violent, oneiric power (the horribly realistic representation of a common dream), its monstrous eroticism (the monster’s unbridled love for the woman, cannibalism, human sacrifice), the unreality of certain sets – or, if you are incapable of letting yourself be taken in by all that, by the acute sensation of unheimlich with which the presence of automata and trickery imbues the whole film – or better still, in combining all these values the film seems to correspond to all that we mean by the adjective ‘poetic’ and in which we had the temerity to hope the cinema would be its most fertile native soil.