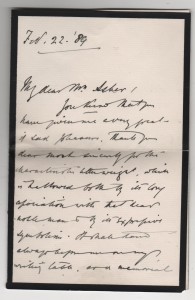

Found—a letter dated February 22nd 1889 from the journalist and novelist Eliza Lynn Linton (1822 – 98). Before she arrived on the scene in the 1840s women who wrote for magazines and newspapers were freelancers. E.L.L., as she became known, was the first salaried female journalist in Britain, and perhaps the world—and one of the best paid, at one time receiving an annual salary which today would be the equivalent of over £50,000.

Found—a letter dated February 22nd 1889 from the journalist and novelist Eliza Lynn Linton (1822 – 98). Before she arrived on the scene in the 1840s women who wrote for magazines and newspapers were freelancers. E.L.L., as she became known, was the first salaried female journalist in Britain, and perhaps the world—and one of the best paid, at one time receiving an annual salary which today would be the equivalent of over £50,000.

Lynn came from a conventional middle class background in Crosthwaite, Cumberland. Her father was a parson and her grandfather Bishop of Carlisle. Attractive and gregarious, she might have married into one of the professions, but instead educated herself in the ancient and modern languages and literature ( her father was too ‘ indolent ‘ to do so himself, she later wrote) and in her early twenties left her comfortable home for London, determined to make a name as a novelist. Her first two novels failed to impress, but undaunted in 1848 she turned to journalism, joining the staff of the highly respected Morning Chronicle. She continued to write short stories and novels and eventually found a degree of success. However, her reputation in literary circles was founded less on her novels and more on her popular journalism, which appeared in All The Year Round, the Monthly Review and the Saturday Review. In perhaps another gesture of defiance she married the woodcut artist, writer and Chartist W. J. Linton , and moved into his ramshackle Lake District house named Brantwood, later to become the home of John Ruskin. The marriage failed and Linton returned to London, where her home became a sort of literary salon.

For an intellectual whose literary style strongly resembled that of the model ‘new woman,’ George Eliot, with whom she corresponded and whose life she wrote, Linton paradoxically devoted much of her journalism to attacking the ideals of feminism. Modern feminists have remained perplexed at this stance, but a reading of the letter reproduced here might offer some explanation. It is addressed to the recently bereaved widow of the celebrated physician Dr Asher Asher who had been the first Scottish Jew to be registered as a physician in Scotland. Linton knew him and was interested in the Jewish causes that he espoused. In the letter she writes of the ‘characteristic letter weight ‘(ie a paperweight) which Mrs Asher had sent her as a memento of her late husband. It was:

‘hallowed both by its long association with that dear noble man by its expressive symbolism . It shall stand always before me on my writing table as a memorial of one I so truly respected and revered and a reminder to be as good as I can be, in imitation of him. I could never be so good as he was, but I can remember him and strive upwards’.

Elsewhere, Linton had urged young women not to pursue careers in areas already dominated by men, and advised wives to support their husbands. Her confession to Mrs Asher appears to mirror her rather traditional view of the place of women in society. [R.M.Healey]