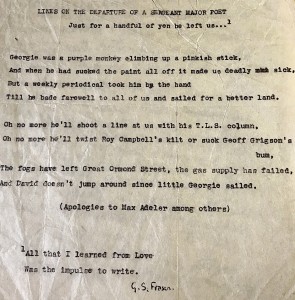

Found on a scrap of paper which looks as if it has been scrunched up into a ball and ironed out flat is this squib on the poet George Barker by G. S. Fraser, the poet and critic.

Found on a scrap of paper which looks as if it has been scrunched up into a ball and ironed out flat is this squib on the poet George Barker by G. S. Fraser, the poet and critic.

The item is signed but not dated, but as it refers to Barker’s departure for Japan in 1939 to take up an appointment as Professor English we must infer that it dates from this time. Fraser looks back at Barker’s short but promising literary career, which then consisted of three volumes of verse, the first of which had been published by David Archer ( the David referred to ) at the Parton Press, and a number of contributions to little magazines, including New Verse, which was founded and edited by the gifted poet and highly influential critic Geoffrey Grigson.

For some reason known only to himself Eliot saw enough in Barker to encourage his efforts and it was Eliot who got the semi-educated Barker ( he didn’t even have a degree) his teaching post in Japan. This, however, was bad timing for Barker, as his burgeoning academic career was curtailed due to the outbreak of the Second World War and he was forced to return to England.

The whole tone of the squib strongly suggests that there was no love lost between Fraser, a good minor poet and a sound critic, and the wayward, uneven and often drunken and opinionated Barker, who if one is to believe all the stories about him, seems to have been a sort of Poundland Dylan Thomas, both as a writer and as a professional scrounger. However, on the subject of alcoholic writers, it is valuable to apply Thomas’s own definition of an alcoholic as ‘someone you dislike who drinks as much as you ‘.

The image of Barker as a ‘ purple monkey’ climbing a pinkish pole ‘is Fraser’s comment on the poet’s willingness to do anything, saying anything and go anywhere to further his career, and the mock heroic epigraph suggests that Fraser was not alone among his contemporaries to resent Barker’s puffed up view of himself.

And when, during the War, Barker poetry’s found support among Thomas and Edith Sitwell, to name but a few, his erstwhile publisher Grigson hit back in the infamous essay ‘ How Much me now your Acrobatics amaze ‘( The Harp of Aeolus, 1947), where Thomas, Sitwell and Barker were jointly accused of writing obscurantist and irrational verbiage. Barker, for instance, was upbraided for this item of nonsense:

O dolphins of my delight I fed with crumbs

Gambading through bright hoops of days,

How much me now your acrobatics amaze

Leaping my one-time ecstasies from Doldrums…

Later still, in 1953, Fraser, himself a former rather unenthusiastic Apocalyptic, voiced his retrospective views of Barker’s contribution to English poetry in his excellent The Modern Writer and His World .To Fraser, both Barker and Thomas, whom he noted lacked a formal academic education, reacted to the socially engaged work of Auden and his followers by concocting much bad poetry that reflected their ‘self indulgent romanticism’. Moreover, as a leading influence on the New Apocalypse, Barker, argued Fraser, was directly responsible for much poetry that was ‘ more florid, more savage, more lavishly ornate’ than had found favour before.

Barker, apparently, still has a following, especially among those who are fascinated by the connection between poetry and bohemianism. However, it would seem that today few readers are willing to buy a modern 600 page biographer of Barker by Robert Fraser (any relation to G.S.?) even when it is remaindered at £2, as it was just a few years ago. [R.M.Healey]