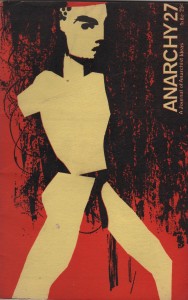

We at Jot 101 only have this copy of Anarchy, issue number 27 ( May 1963) as a guide to what this notable magazine was all about. We do know that it was founded by Colin Ward in 1961 and ran under his editorship until 1970 and that regular contributors included committed anarchists like Nicolas Walter and Harry Baecker. A check list printed on the back of the front cover gives some idea of the political tone of the magazine. Each issue had a theme. The copy we have focuses on ‘Youth ‘, and this seems to have been a prominent talking point in earlier issues, along with calls to oppose capitalism, challenge educational values and generally practise non-violent disobedience and dissent. But Colin Ward was a great advocate for adventure playgrounds, so issue 7 was wholly devoted to this. There were also issues devoted to ‘ Technology, science and anarchism ‘, ‘ De-institutionisation: conflicting strains in anarchism ‘, and ‘ The work of David Wills ‘.

We at Jot 101 only have this copy of Anarchy, issue number 27 ( May 1963) as a guide to what this notable magazine was all about. We do know that it was founded by Colin Ward in 1961 and ran under his editorship until 1970 and that regular contributors included committed anarchists like Nicolas Walter and Harry Baecker. A check list printed on the back of the front cover gives some idea of the political tone of the magazine. Each issue had a theme. The copy we have focuses on ‘Youth ‘, and this seems to have been a prominent talking point in earlier issues, along with calls to oppose capitalism, challenge educational values and generally practise non-violent disobedience and dissent. But Colin Ward was a great advocate for adventure playgrounds, so issue 7 was wholly devoted to this. There were also issues devoted to ‘ Technology, science and anarchism ‘, ‘ De-institutionisation: conflicting strains in anarchism ‘, and ‘ The work of David Wills ‘.

It would be revealing to compare the intellectual level of Anarchy with that of Class War, the agitprop mouthpiece of anarchism in the eighties and onwards run for a time by Ian Bone, who recently became a media bad guy when he cornered the children of Jacob Rees-Mogg and told them that their dad was a ‘horrible’ person. Both magazines have in common the basic tenets of anarchism—anti-capitalism, dissent, ‘ do-it-yourself ‘, and us-versus them—but the violent undercurrent ( ‘Kill the Rich’) that characterises Class War is notably absent from Anarchy, which specifically rejected violent confrontation in favour of powerful arguments that challenged orthodoxies in society. Some of these in this ‘Youth ‘ issue are certainly worth reading.

One of the most perceptive pieces is ‘ The Young One ‘ by Nicolas Walter, which focuses on Cliff Richard, arguably the most popular male singer of a bunch that included Adam Faith, Marty Wilde and Billy Fury, all three of whom Walter saw as genuine working class rebels. In contrast, Cliff, though also working-class, stands apart from his peers as distinctly conformist:

‘ Sometimes he looks like the politician who finds out what most per cent of the voters thinks before he thinks. But he really doesn’t like smoking, drinking, chasing girls and so on. His secret is simple—he has no secret. His personality is simple—he has not personality. He is, as Colin MacInnes once said of Tommy Steele, “ every nice young girl’s boy, every kid’s favourite elder brother, every mother’s cherished adolescent son “ . He is a non-hero of our time, an innocent idol.

He doesn’t do any harm. I wish he would. I wish his “Number One Person in all the world” weren’t Prince Philip. I wish he didn’t want to be Peter Pan. I wish he wanted to be something more than a young one, a parasite on the teenage thing; as he said “we may not be the young ones very long “.I wish the riot in Leicester Square on the evening of January 10thhad been for something more than the chance to see Cliff Richard going to the premiere of his new film. I wish someone would come and lead the second Children’s Crusade, the “new classless class” and finish the teenage revolution once and for all. I wish the kids would refuse to stand for all the rubbish that is handed out to them. Cliff Richard is a nice boy, but I wish he were a really angry young man. I wish he hated someone or something. I wish he weren’t so good, so safe, so useful. I wish he would sing a new song.

He won’t, of course. He’ll go on singing the same song and playing the same part in the same film and doing no harm, as long as it pays. But seriously, though, I can’t hold anything against Cliff. I’m sure his part in Summer Holiday was worth the £100,000 he got for it…’

Walter’s predictions for Cliff didn’t turn out to be true. He didn’t star in any other films after ‘Summer Holiday’, and following the radical change in direction taken by rock music symbolised by the ascendancy of the Beatles and the Stones later in 1963, Cliff’s star, along with those of Wilde, Fury, Steele et al, waned disastrously. Incidentally, on the theme of anarchism and music one wonders what Walters made of Johnny Rotten and Sid Vicious as ‘ anarchists ‘.

This particular issue of Anarchy is also interesting on the work of Ray Gosling, the youth-leader and journalist, whose reputation, following the publication of his memoir, Sum Total, was rapidly on the rise back in 1963. Later he became a radio and TV broadcaster, who travelled round the nation interviewing working class people on their occupations. After a while he became a parody of himself and in the nineties was brilliantly satirised in ‘ People Like Us’, which starred Chris Langham as ‘Ray Mallard ‘ ( geddit ?) .[R. M. Healey]