Winston Churchill, Queen Victoria, Tennyson and William Gladstone admired her; Mark Twain and most of the Press did not. She is said to have outsold Dickens. Some of her novels went into twenty-five or more editions. In an era when writers like H. G. Wells were promoting the New Woman, she reviled this modern phenomenon, and yet some of her heroines could be said to have embodied the virtues—a sense of adventure, a resoluteness and a curiosity– of this type . She promoted Christianity and yet wrote about occultism and transcendence. In her private life she dressed as a rather twee lady, but was a hard-nosed businesswoman in her dealings with publishers and the Press. She had a reputation for ostentation. Owning the grandest house in Stratford-on-Avon ( now an outpost of the University of Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute ), she had acres of trim garden, a tower for writing and a gondola on the river. Her readers adored her, so why, nearly a hundred years after her death is Marie Corelli, arguably the best-selling female author of all time, now almost totally forgotten ? If you wish to buy a first of her many novels today, you need not part with more than a tenner—often much less. From being a former Queen of the subscription libraries Corelli has become a literary curiosity, fit only for examination in academic studies on the cult of celebrity and the role of the popular novel in society.

Winston Churchill, Queen Victoria, Tennyson and William Gladstone admired her; Mark Twain and most of the Press did not. She is said to have outsold Dickens. Some of her novels went into twenty-five or more editions. In an era when writers like H. G. Wells were promoting the New Woman, she reviled this modern phenomenon, and yet some of her heroines could be said to have embodied the virtues—a sense of adventure, a resoluteness and a curiosity– of this type . She promoted Christianity and yet wrote about occultism and transcendence. In her private life she dressed as a rather twee lady, but was a hard-nosed businesswoman in her dealings with publishers and the Press. She had a reputation for ostentation. Owning the grandest house in Stratford-on-Avon ( now an outpost of the University of Birmingham’s Shakespeare Institute ), she had acres of trim garden, a tower for writing and a gondola on the river. Her readers adored her, so why, nearly a hundred years after her death is Marie Corelli, arguably the best-selling female author of all time, now almost totally forgotten ? If you wish to buy a first of her many novels today, you need not part with more than a tenner—often much less. From being a former Queen of the subscription libraries Corelli has become a literary curiosity, fit only for examination in academic studies on the cult of celebrity and the role of the popular novel in society.

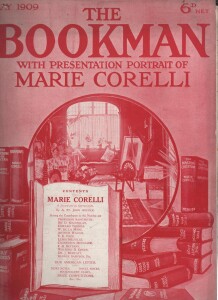

Corelli sold millions of books, but was she ever any good ? The Bookman, a serious middlebrow literary journal, certainly saw her as a significant writer. In May 1909, at the height of her fame, a whole issue was devoted to an appreciation of her life and work by A.St John Adcock, the magazine’s editor, who called on various admirers to support his view of her greatness. Firstly, Adcock takes aim at those ‘cocksure’ critics who set themselves up as the final arbiters of good writing: ‘ There are a thousand times as many critics who have never written a line of criticism, but are not therefore the less cultured, impartial, competent.’ Adcock then turns to the ‘ superior ‘ critics of Marie Corelli:

No living author has been more persistently maligned and sneered at and scouted by certain members of the Press—by the presumptuous and struttingly academic section of it particularly—than has Miss Marie Corelli; and none has won ( by sheer force of her own merits, for the press has never helped her) a wider, more persistently increasing fame and affection among all classes of that intelligent public which reads and judges books, but does not write about them…

Adcock then remarks that the late Queen Victoria, Gladstone and the Empress of Austria sent Corelli congratulatory letters, that the latter invited her for an audience in Buckingham Palace lasting nearly an hour, and that the present King and Queen also expressed their admiration. ‘Here be no common multitude admirers’ avers Adcock, who also adds that while her critics complain that she is ‘ suburban ‘ in her outlook, the fact that there are ‘ some five or six hundred translations of her books selling all over the world ‘ testifies to her ‘ cosmopolitan ‘ popularity.

This brand of sophistry is familiar to anyone versed in the history of literature. Certain critics have always argued that the reading public always knows best. But when Adcock quotes a passage from a letter to Corelli from the publisher Bentley he exposes the weakness of his thesis. Bentley urges the novelist to take strength from the attacks on her:

If an author ascends to fame without attacks, I doubt the permanence of that fame. Carlyle saw nothing in Scott; Milton was almost unread till Addison pointed out the beauty of his writings. But where are Scott and Milton now ? Worshipped as literary gods. ..

This is pure nonsense, of course. The fact that Carlyle didn’t rate Walter Scott is besides the point. The author of Waverley was a literary sensation in his own time and arguably the richest author of the period. Like that of Corelli, his reputation gradually declined following his death, and today it is unlikely to recover. As for Milton, Paradise Losthad gone into several editions before Joseph Addison praised his poetry.

Then instead of trying to strengthen his argument in favour of Corelli as a writer of originality and moral worth Adcock devotes more pages than is necessary defending her record as a conservationist committed to saving Shakespearian relics in her home town, and her run-ins with local societies. And when Adcock returns at last to the novelist’s work he turns to another Corelli admirer , Robert Hichens, to reiterate the familiar defence of her as a woman determined to have her say against all the odds:

‘…she continues to write as she feels, to express her temperament on paper, to put forth, with an amazing vivacity, her opinions, to ‘ go for ‘ all she considers hypocritical, irreligious, sham or diseased…’

In the end it would seem that Adcock felt a need to say why Corelli’s novels were worth reading, but he does so by offering them as a sort of antidote to a world view represented by her detractors:

‘Cold and unemotional natures invariably despise those that are more alive than themselves and so more sensitive to the pleasures and pain, the laughter and pathos, the hopes and the despairs of humanity ; they complacently miscall their own dead indifference culture and dignity, and the finer sensitiveness of those others illiterate emotionalism…’

In contrast, Adcock argues, ‘the style of Miss Corelli’s novels…is everywhere vivid, lucid, glowingly imaginative, burningly alive; through all of them runs the same deep undercurrent of earnestness and strong sincerity…’

Adcock might almost have been describing the work of D.H.Lawrence, who died in the same year as Adcock. Somehow it seems unlikely that the conservative critic and resolute defender of Marie Corelli would have regarded the works of that infinitely greater novelist, whose reputation soared after hisdeath, as equally worthy of praise. [R.M.Healey]

I would be interested in reading a part of one of her novels to see if she is as bad as the critics made her out to be.

James Joyce said of meeting Marcel Proust, “He looked like the hero of The Sorrows of Satan,” which I think was Marie Corelli’s best-selling novel?