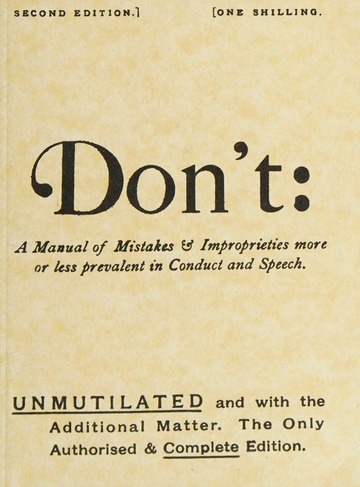

A few years ago we featured a selection of ‘ Don’ts’ from a manual published in the mid twentieth century. This time we are looking at a reprint of an Anglo-American edition dating from 1880 of a best-selling manual of ‘Mistakes and Improprieties ‘ that appeared from the famous publishing house of Field and Tuer. Some of these extracts are accompanied by comments from your Jotter.

At Table

Don’t, as an invited guest, be late to dinner. This is a wrong to your host, to other guests, and to the dinner.

Don’t seat yourself until the ladies are seated or, at a dinner party, until your host or hostess gives the signal. Don’t introduce, if you introduce at all, after the company is seated.

The advice regarding ladies has been redundant for many decades, as sexual equality is now generally recognised.

Don’t tuck your napkin under your chin, or spread it upon your breast. Bibs and tuckers are for the nursery. Don’t spread you napkin over your lap; let it fall over your knee.

What purpose, one may ask, does a napkin serve on someone’s knee ?

Don’t serve gentleman guests at your table before all the ladies are served, including those who are members of your own household.

Regarding the advice of serving ladies first, this again is outdated.

Don’t eat soup from the end of a spoon, but from the side. Don’t gurgle or draw in your breath or make other noises when eating soup. Don’t ask for a second service of soup.

It’s quite awkward, actually, to ‘eat ‘ soup from the end of a spoon. Try it, if you don’t believe me. I agree fully with the ban on noisy eating, especially the use of the expression ‘ Aaaaaah ‘ to denote pleasure.

Don’t bite your bread. Break it off . Don’t break your bread into your soup.

Good advice. Depositing bits of bread into your soup is the equivalent to ‘ dunking’ biscuits into cups of tea. An abhorrent practice tolerated when children do it, but intolerable when done by adults . Grow up.

Don’t eat with your knife. Never pout your knife into your mouth. Go into any restaurant and observe. Don’t load up the fork with food with your knife, and then cart it , as it were to your mouth. Take up the fork what it can easily carry, and no more.

Any restaurant ? This may have been the case at Simpson’s or the Savoy in 1880, but visit a ‘ greasy spoon ‘ today and you might see a number of knives in mouths, especially when there is no spoon handy to gather up that lovely Bisto gravy. Mmmmm.

Don’t use a steel knife with fish. A silver knife is now placed by the side of each plate for the fish course.

In the era before stainless steel was perfected for culinary use (c1915) posh knives often has steel blades and silver handles. Naturally, ordinary steel immediately discolours and corrodes when it come into contact with even mildly acidic food. But fish is not acidic, so it is unlikely to affect steel fish knife blades. Moreover, it is very difficult to get a cutting edge on silver, so one would not use a silver knife to cut up meat. But it cannot be denied that special silver fish knives were used in up- market Victorian households.

Don’t eat vegetables with a spoon. Eat them with a fork. The rule is not to eat anything with a spoon that can be eaten with a fork. Even ices are now often eaten with a fork.

Sound and sensible advice in 1880 as it is in 2025. That is except the bit about eating ices with a fork. Cake, yes. But ice cream? Surely, if it is starting to melt, it would drip through the tines of the fork.

Don’t leave your knife and fork on your plate when you send it for a second supply.

This is pretty obvious practical advice. These implements get in the way of the second helping of food, which is an inconvenience to your host or hostess.

Don’t apply to your neighbour to pass articles when the servant is at hand.

Continue reading