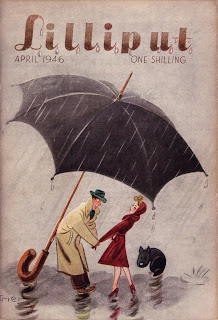

Found in the UK mag Lilliput of April 1946. James Mason's response to recent Ben Hecht book I Hate Actors. A great actor and the best Humbert Humbert so far...look out for his coinage 'hambaiting' in paragraph 5.

EVERYONE says that Walt Disney is the happiest producer in Hollywood because he does not have to put up with actors around his studio. Further evidence is to be found in in the title page of Ben Hecht's recent book "I Hate Actors." And I am prepared to testify that the feeling therein expressed is by no means peculiar to Hollywood.

The abhorrence that flickers in a film producer's eye when the sanctity of his script or the ability of his pet director is rashly questioned by an actor is an awesome vision. It is as if the gates of hell swing open.

For this reason I would recommend to this branch of our art only those aspirants who have exceptional resilience. Those without it are a prey to duodenal ulcers and persecution mania. For tho' the hatred may be mutual the struggle is unequal.

The average producer's civility towards an actor extends only to the moment when the contract is signed. He is a skillful coaxer, all teeth and cigars, and even permits himself to say nice things about the fellow's acting in an effort to ingratiate. Then, almost before the ink is dry, he seems to say "O.K. We've got his signature. Now let's give him hell."

The producer has unlimited opportunities for persecuting the actor. But the reverse is rarely attainable. It should surprise no one therefore that when the rare opportunity present itself the actor seizes it with the righteous zeal of an avenger.

The producer, like the traditional bully, is unable to take punishment, and has no sense of cricket. Failing to hit it off with an actor, he runs whimpering to the producer's association and tries to have him blackballed; just in the same way as he tries to have the professional critic sacked who has given his picture a bad notice. It is unthinkable for an actor, writer, or musician to bellyache about a critic's verdict. But producers have no qualms. Let's face it, I hate producers. (Fortunately there are exceptions. I have worked with them both and like them immensely.)

It must not be thought that the producers have a corner in hambaiting. The relationship between technician and actor has never been the most cordial. Technicians tend to regard an actor as an over-payed, affected fellow whose contribution tho' decorative and even essential is nevertheless strictly subordinate to his own.

The actor, sensing this, becomes easily rattled. He has an exaggerated respect for people who are clever with mechanical contraptions. Tho' he often has a sounder knowledge of the audience reactions, he despairs of being accepted as an intelligent collaborator, or deriving any artistic satisfaction from his movie work. He comes to regard it as a rather uncomfortable means of earning enough money to pay his income tax.

This explains the fact that actors in this country who's careers started in the living theatre can rarely bring themselves to become full-time movie actors. After a bout in the studios they can't wait to get back to the theatre, where inevitably they are so much happier.

Here they have the controlling interest. They can put on a show without anyone else to help them. They can improvise, if need be, on the back of a truck. They are dependent neither on property men nor electricians; directors nor even playwrights. Here are no inhibitions. They can show off as much as they like and no one thinks the less of them. Their final responsibility for their own performances and the nightly stimulant of a live audience make them creative.

This explains the fact that actors in this country who's careers started in the living theatre can rarely bring themselves to become full-time movie actors. After a bout in the studios they can't wait to get back to the theatre, where inevitably they are so much happier.

Here they have the controlling interest. They can put on a show without anyone else to help them. They can improvise, if need be, on the back of a truck. They are dependent neither on property men nor electricians; directors nor even playwrights. Here are no inhibitions. They can show off as much as they like and no one thinks the less of them. Their final responsibility for their own performances and the nightly stimulant of a live audience make them creative.

In film they get the feeling that they aren't allowed to act. They can never understand why the lighting expert is allowed to fool around with his lights for two or three hours, and their own acting rehearsals rate about twenty minutes.

There is the constant demoralising presence of an assistant director whose only thought is to blow his whistle and start shooting. There is the feeling of being encircled by trades unionists who, in the event of an actor exercising his right to be temperamental when operating under difficulties, will stop work and solemnly pass a motion about the incident.

Those sufficiently devoted to the movies become adjusted, but it is hardly surprising if the majority of actors just shrug their shoulders and start looking out for a new play.

Rightly or wrongly, I regard myself as one of the well-adjusted. There is not much that can happen on a studio floor that can give me that sinking feeling, unless, of course, our producer decides to pay us a visit. He has the simplest of all formulas for exciting the homicide in us. All he has to do is to stand around and keep looking at his watch.