Sold on eBay in late 2008 (price unrecorded but circa £180)

Algernon Cecil. British Foreign Secretaries, 1807 – 1916: Studies in Personality and Policy (London: G Bell & Sons, 1927)

This remarkable survival is the copy of Algernon Cecil’s 1927 book about British foreign secretaries owned by the infamous Cambridge spy Guy Burgess. The front free endpaper bears the inscription: ‘Guy Burgess / Eton 1929’. Burgess was seventeen or eighteen and preparing to take up his place at Trinity College, Cambridge.

Inconspicuous enough at first glance – a plain, dark blue hardcover without dustwrapper, a little worn about the edges – the book harbours a wealth of fascinating annotations in the hand of the young intellectual. There are many sentences in the book which Burgess has placed a pencil line under or alongside, such as the observation that Canning, foreign secretary during the Napoleonic Wars, ‘[as] he had a difficulty in understanding the value of a code amongst nations, so he had a difficulty in understanding the obligations of code amongst men’. Elsewhere, Burgess notes well the observation that the Earl of Clarendon (1850s foreign secretary) ‘betray[ed] himself by a kind of fatalism rather than a fund of resourcefulness [so that in the end] he proved somehow unable to take control of the situation, with the inevitable result that it took hold of him’. It is indeed remarkable that the vast bulk of Burgess’s annotations involve criticisms if not outright damnations of character.

There are also, at the bottom of some pages, Burgess’s own thoughts where he is moved to agree or disagree with the author. For example, in response to the claim that, in the lead-up to the First World War, ‘The Russian Government … was quite as inconsiderate of the fate of Europe as the German’, Burgess has written, ‘Not the government, only the war office, for the Tsar was entirely pacific, if weak’. And, annoyed by Lord Grey’s sentiment that ‘Le coeur a ses raisons que la raison ne connait point’, Burgess writes, ‘This seems a very poor reason for going to war!’. Not just acuity of mind is evident in these notes, but so too is the hauteur of the intellectual snob: ‘Anything more absurd than this point of view can hardly be imagined,’ he writes at one point.

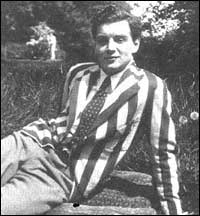

Four years or less after making these notes Burgess was introduced to Kim Philby and his subsequent career as a spy is well-known. The popular perception of Burgess as a bloated and aging cynic shut up in a Moscow apartment is pitiably at odds with the fresh and precocious six-former so engaged with British history in this book.'