The Brock brothers of Cambridge—famous illustrators of Jane Austen, Charles Lamb and Swift, among many others—were all fond of using Georgian antiques and costume as ‘props‘ in their illustrations to canonical texts. They collected all sorts of antiques for this purpose and for all we know they may even have indulged in ‘themed ‘dinner parties on special occasions. The celebrated architect Sir Albert Richardson (1880 -1964) was another ‘old fogey‘ in this respect. His house in Ampthill, Bedfordshire, which was inherited by his grandson, Simon Houfe (b.1942), the industrious author of many reference works on book illustration, was chock full of Georgian furniture and other antiques of the period. As someone with a strong sympathy for the Georgian era, it is easy to imagine him holding ‘Georgian dinner parties‘ complete with period crockery, eating utensils, silver candlesticks and cruets, with the host dressed in a Georgian wig, tunic breeches and shoes with steel buckles.

Doubtless in an age when the Classical world was revered, there must have been many re-enactments of Roman feasts. Perhaps the architect Sir John Soane, whose house in Lincoln’s Inn Fields was ( and still is ) crammed with Classical sculpture, plaster casts and Classical relics of all kinds, had dinners that celebrated the Ancient World. We now know that the Victorian architect Thomas Talbot Bury attended what his trainee, John Wornham Penfold in his diary for 1846 called a ‘ Palladian Party ‘, although it is not known whether Bury was the host or guest at this occasion.

However, accounts of such parties that celebrated the Classical world are thin on the ground (or almost unknown ) in English literature, which is a shame. In French cultural history there is at least one. A description of the ‘ Supper a la Grecque ‘, which was eaten in Paris in 1788, in the year before the Bastille fell, is taken from Austin Dobson’s inestimable Bookman’s Budget (1917), and derived from the Souvenirs of the hostess Mme Vigee-Lebrun, ‘ the artist on whose habitually informal and unpretentious receptions it was a hastily improvised reception ‘ ( Dobson).

‘ Sitting one evening in expectation of her first guests, and listening to her brother’s reading of the Abbe Barthelemy’s recently published Voyage du jeune Anacharsis en Grece, it presently occurred to her to give an Attic character to her little entertainment. The cook was straightaway summoned, and ordered to prepare, secundum artem, specially classic sauces 1) for the eel and pullet of the evening. Some Etruscan vases were borrowed from a compliant collector of the premises, a large screen was decorated with drapery for a background, and the earliest comers, several very pretty women, were summarily costumed a la grecque out of the studio wardrobe. Lebrune-Pindare ( the then popular poet ), arriving opportunely, was at once unpowdered , divested of his side-curls, crowned as Anacreon with a property laurel-wreath, and robes in a purple mantle belonging to the Count de Parois, the accommodating owner of the pottery. The Marquis de Cubieres, following next, was speedily Hellenized, and made to send for his guitar, which his taste for the antique has apparently already prompted him to gild like a lyre. Other guests were similarly

1) Probably some combination of grated cheese, garlic, vinegar and leek…

Continue reading

and perhaps still newsworthy, according to Tatler’s Thousand Most Socially Significant People in 1992.

and perhaps still newsworthy, according to Tatler’s Thousand Most Socially Significant People in 1992.

Joe and Arthur Rank

Joe and Arthur Rank

Found — all 3 issues of The Golden Urn the rare magazine produced at Fiesole by Bernard Berenson, Logan Pearsall Smith and his sister Mary Pearsall Smith (later Mary Berenson.) Of some value – we have catalogued it thus:

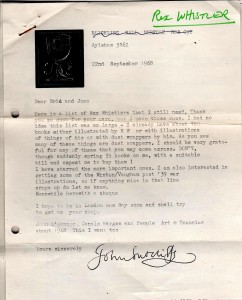

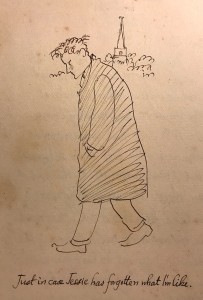

Found — all 3 issues of The Golden Urn the rare magazine produced at Fiesole by Bernard Berenson, Logan Pearsall Smith and his sister Mary Pearsall Smith (later Mary Berenson.) Of some value – we have catalogued it thus: That’s the English Rex rather than the American James McNeill. This covering letter, which was rescued from the archives of the booksellers Eric and Joan Stephens, was sent on 22 September 1968 from the National Trust property Blickling Hall, Norfolk, by the artist and Rex Whistler fan, John Sutcliffe. This letter bears a characteristic scraper board design by Whistler as a sort of letterhead. That’s how much Whistler meant to Sutcliffe.

That’s the English Rex rather than the American James McNeill. This covering letter, which was rescued from the archives of the booksellers Eric and Joan Stephens, was sent on 22 September 1968 from the National Trust property Blickling Hall, Norfolk, by the artist and Rex Whistler fan, John Sutcliffe. This letter bears a characteristic scraper board design by Whistler as a sort of letterhead. That’s how much Whistler meant to Sutcliffe. poem entitled ‘The Dawn’ by the famous Spanish experimental writer

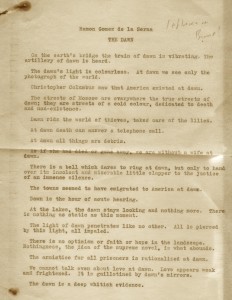

poem entitled ‘The Dawn’ by the famous Spanish experimental writer

Found– Moonlight at the Globe;: An essay in Shakespeare production based on performance of A `Midsummer Night’s Dream at Harrow School (Joseph, London 1946). It was written by

Found– Moonlight at the Globe;: An essay in Shakespeare production based on performance of A `Midsummer Night’s Dream at Harrow School (Joseph, London 1946). It was written by  Found –Life (Dent, London 1921) a

Found –Life (Dent, London 1921) a

Another in the series “I once met” and the sub category “I once danced with..” used when the meeting was only with someone who knew the person (almost always famous.) This is a reference to the popular song “I danced with a man who danced with a girl who danced with the Prince of Wales.” An earlier Jot concerned a meeting with a

Another in the series “I once met” and the sub category “I once danced with..” used when the meeting was only with someone who knew the person (almost always famous.) This is a reference to the popular song “I danced with a man who danced with a girl who danced with the Prince of Wales.” An earlier Jot concerned a meeting with a