.

1) The Ivy

‘A classic name in the restaurant world and one most significant to the men and women of the theatre, the Ivy has at last changed hands. Since its inception until, last year it was under the administration of M. Abel, who so many will think of in his present-day retirement with affection and respect.

Now an entirely new ‘ character’ takes over—a big, boisterous, gentle, tough, kindly Edwardian fish king with a tremendous laugh, and a fair measure of that divine inheritance which is cockney humour. Waving a vast paw, he tells you, ‘I’m in fish, m’ father was in fish, I know fish, and yet I still put vinegar on my oysters because I like ‘em that way. It’s the fish lark that has given me four restaurants in London.’ Here he is apt to pause and reflect—the four restaurants seem both to astonish and tickle him. In a world overrun with meagre men Bernard Walsh stands out, nor alone for his height and build—nor for his silver side-whiskers and fancy weskits, but for his overall rumbustious largeness. Thirty-eight pancakes is his normal portion. ‘I like pancakes’, he explains. He probably has more friends among the press than any other restaurateur in London, and that speaks as loud and hearty as his laugh.

As he also likes meat, and Bernard, we say ‘gets what he wants’, the meat and the fish are quite excellent at the Ivy. Oysters are opened at the table ( the Bill of Fare states this), gives the prices—12s. No 2 Natives, 15s. No 1 Natives, 21s. Colchester—and Bernard adds as we twinkle at each other, ‘ I take the boast, ‘natives’ off my menu, when every fish-boy knows the town has run out of ‘em—which is more than some restaurants do.’ He is correct.

Correct, too, and good value are his Moules Mariniere ( 6s 6d), superb lobsters ( the scene on one occasion when these were cooked in the morning for evening service instead of in the afternoon!), served Cardinal, Newburg, Mornay and Thermidor for 11s. 6d.; his entrecotes( 7s. 6d.), mixed grill ( 10s. 6d.) , chops ( 7s.6d.) and lamb cutlets ( 7s.6d.).

Continue reading

‘Magdalen, both the most beautiful and the most intellectually diverse. Christ Church is an unreconstructed sanctuary of the worst in British snobbery; Balliol is like an American law school, full of politics and ambition. Magdalen has everything : class warfare on even terms, superb tutors, an immense spectrum of interests and tastes’. Other colleges are available…

‘Magdalen, both the most beautiful and the most intellectually diverse. Christ Church is an unreconstructed sanctuary of the worst in British snobbery; Balliol is like an American law school, full of politics and ambition. Magdalen has everything : class warfare on even terms, superb tutors, an immense spectrum of interests and tastes’. Other colleges are available…

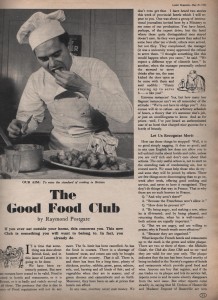

In his Good Food Guide of 1961-62 Raymond Postgate describes the trendy Parkes’ Restaurant at Beauchamp Place (above) in Kensington as ‘ a personal restaurant, dependent upon Mr Ray Parkes, the chef and owner, who offers in his basement at high prices what is claimed to be , and up to date is, haute cuisine.’

In his Good Food Guide of 1961-62 Raymond Postgate describes the trendy Parkes’ Restaurant at Beauchamp Place (above) in Kensington as ‘ a personal restaurant, dependent upon Mr Ray Parkes, the chef and owner, who offers in his basement at high prices what is claimed to be , and up to date is, haute cuisine.’

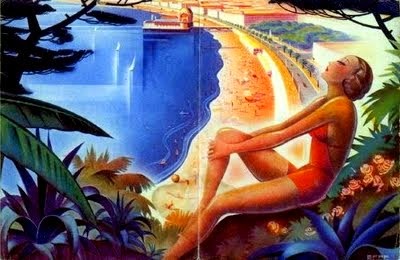

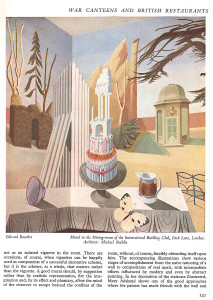

It is a sad fact that most of the best mural paintings executed in canteens, cafes and restaurants in the UK no longer exist. Unlike those executed for some public buildings, those in private premises are subject to the taste of those who take over the property. By far the most notorious example was, of course, the murals executed around 1913 on the walls of Rudolf Stulik’s Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in Percy Street, just off Tottenham Court Road, by Wyndham Lewis, which were later painted over.

It is a sad fact that most of the best mural paintings executed in canteens, cafes and restaurants in the UK no longer exist. Unlike those executed for some public buildings, those in private premises are subject to the taste of those who take over the property. By far the most notorious example was, of course, the murals executed around 1913 on the walls of Rudolf Stulik’s Restaurant de la Tour Eiffel in Percy Street, just off Tottenham Court Road, by Wyndham Lewis, which were later painted over.