When William Bently Capper, an acknowledged authority on hotel management, and incidentally brother of the famous suffragette Maude Capper, published his booklet Dining Out? in 1948, the War had only finished less than three years before. Rationing was still a problem, particularly for diners out. What was likely to be offered at a good West-end restaurant? Was it worth the expense and effort to eat out there?

When William Bently Capper, an acknowledged authority on hotel management, and incidentally brother of the famous suffragette Maude Capper, published his booklet Dining Out? in 1948, the War had only finished less than three years before. Rationing was still a problem, particularly for diners out. What was likely to be offered at a good West-end restaurant? Was it worth the expense and effort to eat out there?

The whole aim of Dining Out? was to assure gourmets that there was little to fear. Restaurants were not exempt from rationing, but as long as diners recognised that certain rules instituted in 1942 by the Ministry of Food’s supremo, Lord Woolton (promoter of the infamous Woolton Pie), applied to eating places, a pleasant meal with wine could be had almost as easily as in the pre-war era. In his chapter entitled ‘Utility meals for Austerity Times’ Capper outlines what problems gourmets were likely to encounter.

‘Every meal served in a public restaurant, breakfast, luncheon, tea and dinner, is limited and regulated by a four-page document known officially as the Meals in Establishments Order…Public meals are restricted to three courses—but that is not the half of it. Certainly, the restaurateur must not serve you more than three courses, but he is also restricted by law as to what he serves in those three courses. You may not have, for instance, more than one main dish; that is, a dish containing more than 25 per cent of its total weight in meat, poultry or game. You may not have more than two subsidiary dishes: dishes containing less than 25 per cent of the foods specified. If you have a main dish, you may have only one subsidiary dish in addition.

Thus, you may have hors d’oeuvres ( a subsidiary dish), followed by meat or chicken, and then a sweet or cheese. Instead of hors d’oeuvres, you may have white fish ( but not fresh water fish!), or soup or, if you forego the sweet, you may have soup, fish and a main dish.

Now, as regards bread. The waiter is not allowed to bring you bread unless you specifically ask for it; so don’t blame the service if you are not offered the usual side roll. If you do ask for it, bread counts as one of the three courses in the meal, and you must sacrifice another dish. The only exceptions to this rule are bread which is served as an integral part of a dish ( bread and butter pudding, welsh rarebit, etc) and bread served with cheese. In the latter case, the bread and cheese together count as one dish.

As might be expected, the introduction of this regulation has practically killed the sale of bread in restaurants—which was its primary object. Very few diners are prepared to give up soup or sweet in order to have a roll, which often remains only half eaten at the end of the meal…

…Within the limitation of the Meals in Establishment Order the chef does his best to compose a coherent, appetising and reasonably nutritious meal out of the bits and pieces at his disposal, with always the over-riding consideration that, by Government decree, the total charge to the consumer must not exceed five shillings—exclusive of beverages, hot or cold. These limitations being understood, it is surprising what a good job most of our leading restaurants make of it…

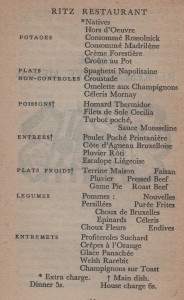

There may be oysters, variety of hors d’oeuvre, as many as four soups, three or four such light plats as omelette or spaghetti, choice of, say, lobster, sole or turbot for the fish course, up to half a dozen entrees ( meat and poultry ), half a dozen cold meats, the same number of vegetables, three or four entremets (sweets) and a couple of savouries. A lordly offering!

But the ‘catch‘ in it is the limitation to three courses, to include one main dish only. In other words, it is the intrusion of the all-important word ‘or‘that makes all the difference. And when one has taken this into account, however many the permutations and combinations possible, the final result is, of necessity, a relatively meagre repast; relatively, that is to say, to the permissible meal of 1938…

…In addition, many West End restaurants have a licence permitting them to make what us known as a “house charge”. This extra charge, permitted in the case of restaurants which have proved that they cannot economically serve a three- course meal for five shillings, varies from 6d to 3s 6d for lunch, and from 6d to 6s for dinner. The amount of the house charge is always printed on the menu…

A few pages later Capper reproduces various menus from some of London’s top restaurants. We have chosen one of the most mouth-watering examples—that of the Ritz. [R.M.Healey]