Mr McBride, an American dealer based in Hartford, Connecticut, published his pocket-sized guide to book collecting and dealing for $9.95 in 1997, but twenty six years later, things in the second hand book world haven’t changed that much, except perhaps that the Internet now plays a much bigger part in the whole business.

This Jot is a commentary on what McBride has to say on collecting and dealing from an American standpoint, though it should be emphasised that throughout the Western world there is very little difference in how collectors and dealers regard books today compared with how such a book maven as Slater ( see previous Jots) saw the business back in 1892.

Let’s start with McBride’s first piece of advice.

Rule One: buy what you like.

‘ Books can be proven to be good investments, but the wisdom to know what to buy seems clearest only in hindsight: “ twenty-five years ago, if you had bought such-and-such a book, it would be worth a hundred times its original price.”. Unfortunately, it is almost impossible to pick the ones that will perform that well out of the millions of new books published in English, world-wide.’

‘ Almost impossible’, perhaps, but not impossible. McBride is talking about new books. But if the author in question is an established figure with a world-wide reputation (perhaps he or she is a Nobel prize winner) the possibility of that author’s latest novel or collection not rising in value is a no-brainer. If you had bought, for example, a first edition of Philip Larkin’s High Window when it appeared in 1974 you could put your house on it rising in value considerably within twenty years, even if you didn’t know that it would be the poet’s final collection.

But new novelists? Yes, ‘almost impossible ‘.In the same year (1997) that McBride’s guide appeared someone called J. K. Rowling brought out Harry Potter and the Philosophers Stone , following its rejection by a number of leading publishers of children’s fiction. Each year literally thousands of new books for children are published in the UK. No-one could have predicted that Ms Rowling’s book would turn out to be the international sensation that it became. Bloomsbury obviously had faith in their new author, but not faith enough to bring out more than a smallish edition. The book received mainly rave reviews for the originality of its plot and characterisation. The edition sold out and a new edition was reprinted. Fans of the book couldn’t wait for the next Harry Potter story and they didn’t have to wait long. Readers who had bought the debut novel because they liked stories about schoolboys defying their parents and adults and getting mixed up in magic in a special school for magicians found, twenty years later, that their pocket money had bought a book worth many thousands of pounds. They had bought what they liked and had ended up with a good ‘investment ‘.

Continue reading

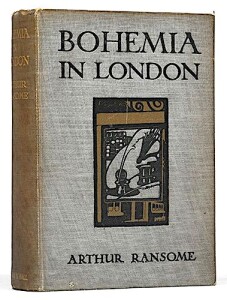

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually. in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.

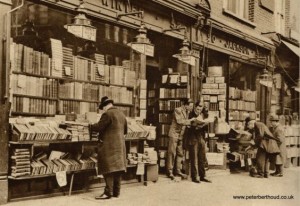

in collectable condition fetching £500 or more. We at Jot 101 had not imagined the travel writer and biographer Walter Jerrold ( 1865 – 1929 ) to be a frequenter of second-hand bookstalls, but there he is as an unabashed collector of ‘unconsidered trifles ‘ in Autolycus of the Bookstalls (1902), a collection of articles on book-collecting that first appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, the New Age, and Londoner.

We at Jot 101 had not imagined the travel writer and biographer Walter Jerrold ( 1865 – 1929 ) to be a frequenter of second-hand bookstalls, but there he is as an unabashed collector of ‘unconsidered trifles ‘ in Autolycus of the Bookstalls (1902), a collection of articles on book-collecting that first appeared in The Pall Mall Gazette, Daily News, the New Age, and Londoner.