We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

We have seen ( previous Jot) how, in his first book, Bohemia in London, the young Arthur Ransome was happy to confess his bibliophilia. He seemed to love second hand books more than brand new ones, but he hated the practice of selling unwanted books ( whether new or second hand, he doesn’t say) given as gifts ending up on bookseller’s shelves. Certain people feel no guilt about doing this; they assume, wrongly, that they will never be found out, but if the gift is inscribed there is a reasonable chance that the bibliophile who gifted the book will discover it in some bookshop or bookstall eventually.

What is far more reprehensible, however, is the sense of betrayal felt by someone who having taken into their home a friend, colleague or relation down on their luck, discovers that this lodger has been stealing books from their shelves to sell to book dealers. This wouldn’t have happened to the impoverished young Ransome, of course, but it did happen to the comparatively well-off Geoffrey Grigson while editor of New Verse.Grigson, like Ransome in his time, would’ve been sent dozens of books to review each week, most of which he would have sold to second hand booksellers. Other books for review he would have kept for his own collection, particularly those published by fellow poets he particularly admired, such as Auden, MacNeice and Wyndham Lewis. Grigson also held regular parties for his New Versecontributors at his home in Keats Grove, and it is more than likely that on these occasions he would have asked some of his guests to sign the review copies he had retained for his own use. It is equally, likely, of course, that a grateful guest would have presented a signed copy of his book to Grigson.

Whatever the circumstances, Grigson must have assembled a decent collection of books, including ‘modern firsts’ at Keats Grove. And it was at Keats Grove that Grigson and his American wife Frances first met the young Ruthven Todd, ‘an unemployable, persistent, rather squalid-looking tall, grey oddity ‘ who wrote poetry and turned out to be a book thief. At one point he actually showed Grigson a copy of MacNeice’s Blind Fireworksinscribed by the poet to his wife. This could only have come from the library of MacNeice himself. Anyway, a few years later Grigson and his wife moved to Wildwood Terrace, not far from the Old Bush and Bush, and it was here that Todd turned up again, this time to take up the offer of bed and board for 10 shillings a week. Unfortunately, Todd couldn’t even afford this negligible sum, so he took to stealing from Grigson’s bookshelves. The whole sorry story, as Grigson tells it in Recollections,is distinctly farcical:

‘…a bookseller whose shop I frequented in Cecil Court..…told me he had just bought ten shillings’ worth of books in one of which was a letter addressed to me. I was in that shop again some weeks later: the bookseller had bought more books—always ten shillings’ worth or thereabouts—from the same seller, in one of which this time was my signature, and the seller was—Ruthven Todd. Between us we kept the arrangement going for some time. Ruthven bought the books to Cecil Court, the bookseller paid him the required ten shillings. Ruthven with scrupulous regularity paid the ten shillings to me wife, and I went down to Cecil Court, and retrieved the books, for ten shillings… We never taxed the Innocent Thief with his theft, this generous creature who seldom came to see us without some present, paid for God knows how, for the children .

But to return to Arthur Ransome. Bookstalls were one source of second hand books that he visited regularly.Those that lined the Farringdon Road on the edge of the City were favourite haunts. The stalls, which dated at least from the 1870s, had originally combined second hand goods of all kinds with second hand books, but by Ransome’s time the Jeffrey family, who specialised in old books, had come to dominate the stalls and the family ran the place until the last Jeffrey died in the 1990s ( see previous blogs ).

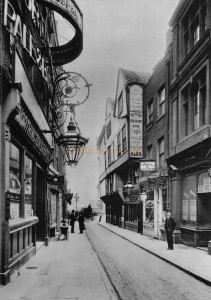

Ransome also mentions Bedford Street and ‘Booksellers’ Row ‘. Bedford Street, which joins Covent Garden to the Strand, is not particularly well known for its second hand bookshops, but that part of London has an association with the book trade generally. Better known is nearby ‘ Booksellers’ Row ‘, the genteel name for the notorious Holywell Street, a narrow, rather picturesque, thoroughfare that ran parallel to the Strand on the north side, and the equally picturesque Wych Street, which branched off on the east side on its way to Covent Garden. Both were streets that had specialised in radical pamphlets and erotic literature since the early eighteenth century. At one point in the mid nineteenth century it was calculated that Holywell Street alone boasted fifty bookshops selling pornographic literature that catered for all tastes. Following the death in 1868 of arguably its most infamous publisher/bookseller William Dugdale, who was responsible for such gems as The Battles of Venus: a descriptive dissertation of the various modes of enjoyment of the Female Sex ( 1850 – 60) and Scenes in the Seraglio, or the Adventures of a Young Lady in the Harem of the Grand Sultan( 1855 – 60) this particular street seems to have cleaned up its act somewhat. Many of the bookshops closed down and their placed were taken by ‘ respectable ‘grocers, fishmonger and butchers. However by the turn of the century the fate of Holywell Street and part of Wych Street (above) had been sealed. Partly as a result of the public outcry (voiced in Parliament and elsewhere) and partly because other slum-ridden sections of that area of the metropolis, principally Seven Dials, had already been cleared for the building of Charing Cross Road and Shaftesbury Avenue ( see earlier Jot) the authorities decided that the east end of the Strand was far too narrow for the increasing amount of traffic. The Strand was duly widened and the new and elegant crescent-shaped Aldwych emerged on the site of Holywell Street. In addition, a new and very wide thoroughfare complete with tram tunnel was constructed from Aldwych to High Holborn.

Ransome must have witnessed all this construction work, although he doesn’t mention it in Bohemia. But there is definitely a valedictory tone in his account of Booksellers’ Row, though he is careful not to mention its past notoriety or whether he himself was a frequent visitor to its seedy establishments. In 1907 the memory of Holywell Street, which some commentators decried as having played a part in the degradation of the public morals in Great Britain, was still raw. It is not likely that the young and distinctly rebellious Ransome shared these views. We don’t know whether he had a taste for salacious literature, but we do know that his leftist leanings were to take him to the emerging Soviet Union in 1917 and that his fact-finding tour resulted in a short book that reflected his very favourable opinion of the new nation and its leaders. [R.M.Healey]

“a copy of MacNeice’s Blind Fireworks inscribed by the poet to his wife. This could only have come from the library of MacNeice himself. ”

Not necessarily. Was the lady still MacNeice’s wife or on good terms with him when Todd…. acquired it, though it doesn’t seem likely he got hold of it legally? There was the case a few years ago when V.S. Naipaul and Paul Theroux fell out over a library clear-out. As Todd also made a living writing a detective story a month he probably could have made enough money to pay Grigson if he chose to.

Oddly enough Roger i was the dealer who bought the Theroux books from VS Naipaul. It caused an unholy row between when they got on to the market. At the time VSN’s wife was slightly hesitant about selling the books signed to her husband by Theroux but he said, ‘…no problem- Paul will just sent some more!’