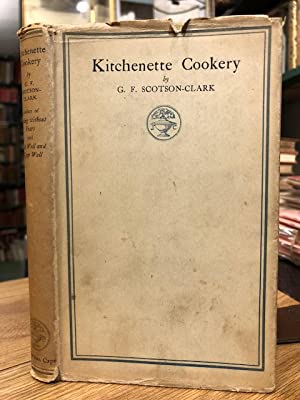

Talented artist, friend of Beardsley and writer on cookery, G. F. Scotson Clark ( see previous Jots) , was particularly fond of curries which, though they had been the staple of Anglo-Indian families since the late eighteenth century, were only just becoming popular with restaurant customers in the United Kingdom when his first book, Eating Without Fears , appeared in 1924. Here are his views on curries.

‘ I was brought up on curry. Mine is an Anglo-Indian family. So fond was my mother of curry, that she used to declare she was weaned on it. In our old home one day we would have” Uncle Edward’s “curry, on another,“ Uncle Charles’s”. Uncle Charles was the only member of the family who was a Madrasi. All the rest were Bengalis, and our early recollections of Uncle Charles—when I was about seven or eight years old—are that his curries were infernally hot. The older he got—and he was close to ninety then—the hotter became his curries, until at last no one but himself could eat them. He lived in a curious old house in Bayswater, a house literally walled with books. The doubled drawing-room upstairs was always scattered with papers. He wrote from morning till night, but what he wrote I know not, except that he was the author of a Telegu dictionary in some twelve volumes, which I am sure no one ever read…

There is no necessity for a curry to be hot—hot with pepper to burn the tongue. Too much curry powder, or curry powder insufficiently cooked, is generally the cause of this. At the same time it should be piquant and not like a stew with a flavouring of curry.

When the gas was cut off by the Gas Board at his small ‘ Bohemian Club ‘in London frequented by ‘ artists, writers, barristers, soldiers, sailors, the clergy, including two bishops’, Scotson Clark volunteered to cook an Indian dinner using only a chafing dish and a spirit stove. The menu was:

Mulligatawny Soup

Kedgeree

Curry of Veal and Rice

with Bombay Ducks, Chutney, and

West Indian Pickles

Iced oranges

Fruit Curry

The complicated recipe for mulligatawny soup is as follows:

Continue reading

Found, The Dinner Knell, the book published just months before his death aged 52 by prolific journalist and fin de siecle expert T(homas ) Earle Welby, (1881 – 1933). The premature demise of Welby, who was known to his New Statesman readers as ‘Stet’, may have had something to do with a love of food that informs much of his writing, including this particularly lively excursion into the world of gastronomy.

Found, The Dinner Knell, the book published just months before his death aged 52 by prolific journalist and fin de siecle expert T(homas ) Earle Welby, (1881 – 1933). The premature demise of Welby, who was known to his New Statesman readers as ‘Stet’, may have had something to do with a love of food that informs much of his writing, including this particularly lively excursion into the world of gastronomy.

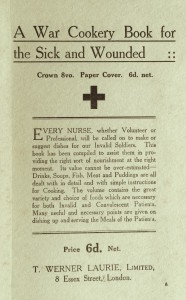

Found in a pamphlet of c 1796, entitled On Food, and particularly of Feeding the Poor by the pioneer of cheaply produced dishes , Benjamin, Count Rumford, is a recipe that is not likely to catch on among modern foodies, though those who like experimenting with trendy cereals such as Quinoa, might find it intriguing. To me it sounds like a superior thickened gruel, but others might disagree.

Found in a pamphlet of c 1796, entitled On Food, and particularly of Feeding the Poor by the pioneer of cheaply produced dishes , Benjamin, Count Rumford, is a recipe that is not likely to catch on among modern foodies, though those who like experimenting with trendy cereals such as Quinoa, might find it intriguing. To me it sounds like a superior thickened gruel, but others might disagree.