Following on from a recent Jot exploring what the BBC were offering as TV entertainment for Christmas 1932 — half an hour from 11 pm onwards showing either a singer crooning into a microphone, female dancers prancing about in special costumes, or a short poem or play – we at Jot HQ thought it might be interesting to examine what listeners could expect to enjoy throughout the rest of the festive season.

Following on from a recent Jot exploring what the BBC were offering as TV entertainment for Christmas 1932 — half an hour from 11 pm onwards showing either a singer crooning into a microphone, female dancers prancing about in special costumes, or a short poem or play – we at Jot HQ thought it might be interesting to examine what listeners could expect to enjoy throughout the rest of the festive season.

First, we should explain that in the ‘thirties the Radio Times, though ostensibly a guide to radio schedules, was also a kind of feature magazine in which along with the programme information could be found other entertainment in the form of short stories or feature articles. In this particular issue we find material by well-known authors which, in most cases, had little or anything to do with the actual programmes. For instance, in this special Christmas number we find a tale by Compton Mackenzie entitled ‘ New Lamps for Old ‘, a new Lord Peter Wimsey story from Dorothy L. Sayers called ‘ The Queen’s Square, a satirical skit by Winifred Holtby entitled ‘ Mr Ming Escapes Christmas’, a memoir from popular travel writer S. P. B. Mais , a comic confection by D. B. Wyndham Lewis and a rather tiresome faux medieval dramatic piece by Eleanor and Herbert Farjeon. There were also a couple of ‘poems ‘and some similarly light features by a handful of lesser known writers.

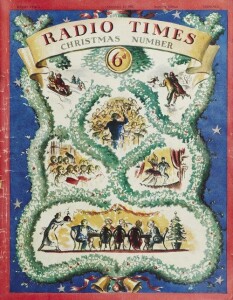

It must be said that while the writing sometimes fails to impress, the illustrations that accompany it are usually charming in the best traditions of the Radio Times. For instance the cover ( see earlier Jot ) of the magazine is characteristic art work from book illustrator Edward Ardizonne, while some superb illustrations from the gifted illustrator John Austen , who was to become a favourite of the Radio Times, decorated the borders of the Farjeon piece. Other notable illustrators included Mervyn Wilson, Roland Pym and Clixby Watson. It goes without saying too that the adverts ( some full page) are no less captivating, most notably the wonderful back cover colour advert for Bovril by Alfred Lees featuring the ghost of Jacob Marley.

As for the radio programmes, listeners were treated to a diet composed almost entirely of live light or classical music, with the odd play, poem or similar seasonal feature, such a Church Service, thrown in. For instance, on Christmas Day, a short Christmas Service from the London studio was followed at 12.30 by an hour long concert of light music, including pieces by Lehar, Rebikov ( ‘ March of the Gnomes’, anyone ?) and Eric Coates. Afterwards, a pianist named Raie da Costa played eight pieces, including seven of his own arrangements, for half an hour. Sharp at 2 pm the stage was set for George V to deliver his ‘message to the empire ‘from Sandringham. After a recital of gramophone records (content not disclosed ) and a story for children, there were two hours of mixed classical and contemporary music, including a piece by Peter Warlock, before some religious poems by Thomas Traherne were recited for some reason by a naval officer called Oswald Tuck.

In the evening a religious service relayed from Winchester Cathedral and more music ( light and classical ) was punctuated at 8.45 by an appeal from the Prime Minister, Ramsay Macdonald, on behalf of The British Wireless for the Blind Fund, for contributions to supply blind listeners with a further 2,800 wireless receivers. London regional programmes for the day included a Grieg recital by the celebrated pianist Arthur de Greef, who had studied under Liszt and was a personal friend of Grieg himself, and a performance by the eccentric Australian pianist Eileen Joyce, a great favourite worldwide, whose gimmick was to change her costume several times during a concert to suit the personality of each composer. It is not known whether she did so on this particular occasion, as she played the work of five composers, which would have meant a lot of costume changes!

The fare for Boxing Day was a little more varied and a little more Chrismassy. For instance there was a review of new books by G. K. Chesterton and as a special treat a masterly impersonation by the gifted actor Bransby Williams of Dickens’ Scrooge followed by a ‘ radio pantomime ‘ entitled ‘ Jack and the Beanstalk ‘ in which the trained actor Harman Grisewood, later to become one of the ‘ suits ‘ at BBC Radio, played ‘The Spirit of Pantomime ‘. The London regional offerings for the day were principally light music, including ‘ selections from Noel Coward ‘ and something called ‘ popular opera ‘, ie Verdi and Humperdinck.

So far there hadn’t been much in the way of comedy, unless you count pantomime as such, but the BBC wasn’t to be outdone by the Music Halls, who at the fag end of their popularity were now offering comic ‘ reviews ‘. At 9.20 on New Year’s Eve listeners were treated to ‘Vaudeville ‘. This turns out to be an hour of crooning interspersed with comic turns by Harry Hemsley ( ‘ child impersonations ‘), Nosmo King, ‘ the black-faced comedian and partner’ and the comedienne Nellie Wallace, who is shown in an inset photo dressed up as a clown. Earlier on in the evening the Midland region had broadcast an apparently satirical take on provincial government featuring Alderman Luke Loofah, the Mayor of Slow-on-the Uptake with music by the Slow-on-the-Uptake Tuba Band. Today we might ask why comedy in the early years of the BBC was too often accompanied by entirely unnecessary jazz music or a brass band. Even ‘The Goons’ had a musical interlude. [RR]

According to Wikipedia Oswald Tuck was multi-talented – an expert mathematician, the youngest ever Fellow of the Royal Astronomical Society, a Japanese linguist, a historian (even though he had no degree he was a candidate for a history professorship), an intelligence officer and cryptanalyst – so his role raising interest in Traherne isn’t as odd as it might seem now, especially as Traherne’s work had only recently been discovered and published, so enthusiasts were probably rarer than they are now.

Fair enough. I suspected that there must have been a reason why a naval officer had been chosen to talk on Traherne, but was unaware of Mr Tuck’s abilities in other areas. As for Traherne, I was also aware that the bookseller Dobell had ‘ discovered ‘ him c 1910. This doesn’t quite explain why Mr Tuck saw himself as another explicator. Perhaps as a cryptographer he had found other writings.

Incidentally, Geoffrey Grigson was a leading populariser of the work of Christopher Smart and John Clare and could be said to have ‘ discovered ‘ the poems of William Diaper in the late 1940s, which discovery led to a scholarly edition in 1952.

In 1932 the BBC seems to have been an odd mixture of professionalism and amateurishness, with friendship or nepotism often playing a part in people appearing. The great Jackie Fisher said “Nepotism means efficiency”, so it would be appropriate to invite a naval officer to speak on a whim.

I don’t know, obviously, but I’d guess that it wasn’t a case of Tuck being selected to explicate Traherne, but of Tuck being asked if he’s like to give a talk and choosing Traherne as a subject himself. One possible connexion between Tuck and senior BBC officials is A.J. Alan (Thomas Harrison Lambert), a popular radio story-teller who like Tuck was engaged in government cryptanalysis and intelligence work.

You are right Traherne has become better known in the last fifty years. Rather like John Clare and even Christopher Smart (without the discoveries)

Traherne was even less known than Clare or Kit Smart – his poems were ascribed to Henry Vaughan or Vaughan’s brother when they were first found and only published under his own name in the twentieth century and the Centuries of Meditations even later, so Tuck would have been a rare pioneer in admiring him. T.S. Eliot said he was “more a mystic than a poet”. I’d guess that Finzi’s Dies Natalis is probably what led most of his admirers to Traherne. It was certainly my first encounter with him.