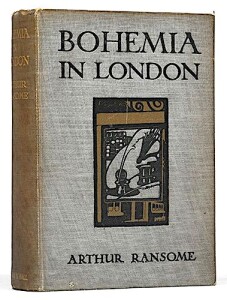

Years before he achieved fame as the author of Swallows and AmazonsArthur Ransome published his first book, Bohemia in London(1907), which is now very sought after, copies  in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.

in collectable condition fetching £500 or more.

At the time he was working as a poorly paid journalist, but as Bohemia strongly suggests, he was spending most of his salary gathering material for this book by mingling with Bohemian types of all kinds mainly in pubs in and around Chelsea, where he lived. He was also buying second hand books. One of the opening anecdotes of his chapter on bookshops and bookstalls concerns the copy of Burton’s Anatomy of Melancholy that he acquired for 8/- from a book dealer in central London. At the time he had just a few shillings in his pocket and was planning to visit a restaurant on the way home to his digs. He ended up spending everything he had on him which meant carrying the two heavy volumes under his arms, going hungry that evening and having to walk home, rather than taking an omnibus or Underground train. Ransome also doesn’t give many details about the edition of the Anatomy, but we can be fairly sure that at 8/- it wasn’t a very early edition and certainly not a first.

The appeal of such an old fashioned tome to someone with an addiction to such treasures reminds us of Lamb’s essay entitled ‘ Old China ‘ in which his sister Mary, in the guise of Bridget, recalls the acquisition of a folio Beaumont and Fletcher that her brother had ‘ dragged home late at night from Barker’s in Covent-garden ‘ to their home in Colebrooke Row, Islington in the early 1800s.

‘ Do you remember how we eyed it for weeks before we could make up our minds to the purchase, and had not come to a determination till it was near ten o’clock f the Saturday night, when you set off from Islington, fearing you should be too late —and when the old bookseller with some grumbling opened his shop and by the twinkling taper ( for he was setting bedwards ) lighted out the relic from his dusty treasures—when you lugged it home, wishing it were twice as cumbersome —and when you presented it to me —and when you were exploring the perfectness of it ( collating you called it )—and while I was repairing some of the loose leaves with paste, which you patience would not suffer to be left till day-break—was there no pleasure in being a poor man ?’

Back then there were no omnibuses in London (the first appearing in 1829) and certainly no Underground trains, so most bibliophiles like Lamb with small pockets had to shift for themselves. It is possible that Ransome was inspired by Lamb’s essay. However, it must be said that when it comes to books, old wine in new bottles lacks the appeal of old wine in old bottles. Lamb said as much in another essay , ‘ Detached thoughts on books and reading’ when he deplores the practice of reissuing antique texts in smaller format, modern type and between plain boards. He compared his adored Beaumont and Fletcher with a modern edition of Burton’s Anatomy:

‘I cannot read Beaumont and Fletcher but in Folio. The octavo editions are painful to look at. I have no sympathy with them….I do not know a more heartless sight than the reprint of the Anatomy of Melancholy. What need was there of unearthing the bones of that fantastic old great man, to expose them in a winding-sheet of the newest fashion to modern censure ? What hapless stationer could dream of Burton ever becoming popular ?’

Ransome seems to have had fewer scruples about reading old texts in newer editions. He appears to have been someone who just preferred second hand books to brand new ones. One of his complaints is having to juxtapose new books given him to review with his own second hand books. He admits to tolerating books that his friends had published, but disliking the way in which their flashily printed boards contrasted with his own more sober (leather, bare boards with simple paper spine labels and plain trade bindings). And here we must point out that in this Edwardian period the book wrapper was just beginning to develop as a protective measure. It is true that very plain wrappers can occasionally be found on early Victorian books, but examples are incredibly rare and as such fetch quite high prices. The world’s expert on the history of the dust wrapper, Thomas Tanselle, published a very interesting study of this topic a few years ago.

Ransome also wrote on the chore of cutting pages, or as we might say, the dilemma of ‘ to cut or not to cut ‘..He writes about the novelty of buying a book with its page edges ‘ uncut ‘ and having to spend valuable time cutting these edges with a knife. There was a time when dealers in their catalogues proudly described a book as being ‘ uncut ‘, which obviously meant that the book in question had never been read completely. To some collectors an uncut volume was preferred to a conventional ‘ cut ‘ one simply because it would not have been marked in any way by a reader’s underlinings, annotations and dirty, perhaps greasy, fingers. On the other hand, perhaps an uncut book had been left in that state because it was felt to be not worth reading.

To be continued… [ RR]

According to Richard Heber “No gentleman can be without three copies of a book: one for show, one for use and one for borrowers.”

Presumably the books for show were uncut. I am surprised by his generosity to borrowers. When I came across Edwin Arlington Robinson’s lines “Once I had friends who borrowed my books and set wet glasses om them.” my first thought was “At least you got them back!”

I obviously had a lower class of friends than Heber or Robinson.

Heber set a very highh standard, possibly the book to lend was just a reading copy…