( Initially from J. D. Mortimer, An Anthology of the Home Counties 1947), but including commentaries from other sources.

The Hermit of Ickenham ( lived c 1655)

Roger Crabb, an eccentric character, of whom there is a curious account in a very rare pamphlet, entitled ‘The English Hermit, or the Wonder of the Age (1655), lived many years in a cottage at Ickenham, where he subsisted on three farthings a week, his food being bran, mallows, dock leaves, grass and the produce of a small garden; his drink water; for he esteemed it a sin to eat any living creature, or use any other beverage. Towards the latter part of his life he removed to Bethnall Green, where he died in 1680, and was buried at Stepney.

Daniel Lysons, The Environs of London

Actually, Mr Crabb seems to have lived on a rather healthy vegan diet from the age of twenty, when he was a soldier on the parliamentary side during the English Civil War. He later became a haberdasher in Chesham, Bucks and afterwards retired to Ickenham, where he became a pacifist and a proto-Anarchist. He was an anti-Sabbatarian, arguing that Sunday was not a special day. He inveighed against the evils of property, the Church and the Universities. According to one source, he ate potatoes and carrots as part of his vegan diet, but towards the end of his life subsisted mainly on bran, dock leaves (Rumex) and parsnips. Bran is full of vitamins, as are dock leaves, but the latter also contains oxalates, which can induce kidney stones if eaten to excess. All parts of the common mallow are nutritious, however. The leaves can be boiled and made into a soup, and the roots can be candied.

The Frimley Hermit ( 17th century)

At the end of this Hundred, I must not forget my noble friend, Mr Charles Howard’s Cottage of Retirement( which he called his Castle) which lay in the middle of a vast healthy country, far from any Road or Village in the hope of a healthy Mountain, where, in the troublesome times he withdrew from the wicked World, and enjoyed himself here, where he had only one Floor, his little Dining Room, a Kitchen, a Chapel, and a Laboratory. His utensils were all of Wood or Earth; near him were half a Dozen Cottages more, on whom he shew’d much compassion and charity.

John Aubrey: Perambulation of Surrey

The Internet is silent on Mr Howard and his Cottage. The aristocratic Howards of Effingham ( in Surrey) don’t seem to be related to this particular Howard. We at Jot HQ would welcome any information on Frimley’s Hermit.

The Hermit of Great Wymondley ( 1874)

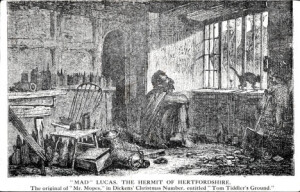

He discarded thenceforth every comfort and luxury of life. He lived in what had been the kitchen, literally in sackcloth and ashes. For his raiment he has a blanket; for his bed a heap of cinders. Hs food was of the humblest, and his unkempt hair, his grimy face and blackened skin made him a pitiable object, with scarcely a trace of humanity discernible. His unfounded terror of his relatives and of others soon displayed itself. Stanchions and logs of timber were affixed to the doors amd windows with bands of iron, and everywhere rivets, bolts and bars were placed to shield him from those imaginary dangers of which he stood in mortal fear. The only furniture in the kitchen where he took up his abode was a chair and table. In this den he passed the remainder of his days , very seldom going outside the door. The fire was hardly ever allowed to go out , and as the cinders accumulated he used to scrape them back with his hands, so that when he died the room was so full that it was difficult to pass from it to other parts of the house. On these cinders he used to sleep and on them he would sit when he took his meals.

Hertfordshire Express, 1874.

‘Mad ‘ James Lucas was quite a character in the Hitchin area and was visited by all sorts of people from locals to the curious from far afield. When staying with Lord Lytton at Knebworth House, Dickens paid a call and was so impressed that he portrayed Lucas as ‘ Mr Mopes ‘ in his short story ‘Tom Tiddler’s Ground ‘ (1861). In Reginald Hind’s Worthies of Hitchin Lucas is given a whole chapter to himself. Hine quotes from an article by the journalist Edward Copping in which Lucas declares that:

‘ I have spoken here with the very highest in the land and with the very lowest. They are all as one to me. I adapt my conversation to their capacity and station. The other day I had some of the London swell mob here , and every day I have no end of tramps. I can talk slang with a thief and religion with a clergyman. Last year I had 12,000 visitors and as many as 240 in a single day.’

Doubtless there is a degree of exaggeration here, but many of these visitors may have been local fans of Dickens. As for the Hermit’s alleged ‘ madness ‘, authorities disagreed. The biographer of Dickens, John Forster, who was also a Commissioner of Lunacy, could find no madness in him. On the contrary, he appeared to have a sharp intellect. Others, including Dickens himself , found him ‘ morally insane ‘. Dickens thought him a sort of poseur who revelled in his notoriety.

According to Hine, he was born in London in 1813 to a wealthy West Indies merchant. Lucas was a disorderly and recalcitrant youth whose education had been plagued by truancy. The family moved to Elmwood House, Great Wymondley, with the hope that the conduct of this errant son might improve. It didn’t, and on the death of his father in 1830, it became even more extreme and he was obliged to accept an attendant living with him. His mother’s death in 1849 brought on some kind of mental breakdown. Instead of having her decaying corpse removed for burial, he kept vigil over it for nearly three months and only gave it up when local magistrates broke into the house and took it for burial. His life as a hermit started from this point. Lucas violently resented Dickens for misrepresenting him in his story. He also hated agents of the law and other figures of authority. The only humans he seemed to welcome were children and tramps, and to these he gave money or other gifts.

A Tunbridge Character (1728)

Among the infinite variety of People now here there is a Madman, surnamed Drapier, who strikes us all with pannick, Fear and affords us diversion at the same time. He has raised a regiment and enlists his Soldiers in a manner not a little extraordinary. He fixes on any Gentleman who his wild Imagination represents as fit for Martial exploits, and holding a pistol to the pore Captives Breast, obliges him to open a vein and write his name in Blood upon the Regimental Flag. Some have leap’t out of Window to escape the Ceremony of bleeding , but many others have tamely submitted, and they every morning in Military Order at his Heels. He has in his Suite an Irish Viscount and an English Baronet , three Jews, five Merchants, and a supercargo. These are the Chiefe, but the whole Regiment consists of Twenty-Seven. All agree he should go the Bedlam, but none dare send him there. The unbelieving Jews tremble at the Sight of Him , and the sober Citizens of London turn pale when he enters the Room. To his natural heat he adds the strength of Liquor, and is a most terrible Hector.

Lord Boyle

We are unsure as to whether Boyle means Tonbridge or Tunbridge (Wells), which are both in Kent. In any case, Mr Drapier doesn’t seem to be known to the Internet. Again, information from those in the Jottosphere is welcome.

R.M.Healey.