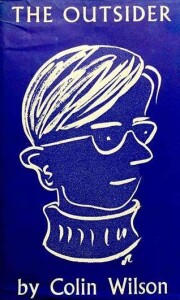

Found among the papers of the academic Patrick O’Donoghue, two clippings of reviews—by Philip Toynbee and Cyril Connolly—of The Outsider (1956), the astonishing debut of the twenty-four year old, largely self-taught, Colin Wilson that branded him a fully paid up member of the Angry Young Men brigade and ‘ Britain’s first, and so far last, home-grown existentialist star’.

Found among the papers of the academic Patrick O’Donoghue, two clippings of reviews—by Philip Toynbee and Cyril Connolly—of The Outsider (1956), the astonishing debut of the twenty-four year old, largely self-taught, Colin Wilson that branded him a fully paid up member of the Angry Young Men brigade and ‘ Britain’s first, and so far last, home-grown existentialist star’.

An ‘Angry Young Man’ because, rather fortunately for Wilson, The Outsider appeared from the leftish publisher Gollancz in the same month ( May) that John Osborne’s ‘Look Back in Anger ‘ opened at the Royal Court in London. We don’t know whether the two very different reviewers—Toynbee, a Bohemian critic in his forties and a communist, who had been expelled from Rugby School, and Connolly, very much of the Auden Generation, had seen the play before they wrote their reviews, but had they done so, judging from the enthusiasm with which they wrote about the book , it is possible that they identified both book and play as evidence of a new dissatisfaction among the thinking young Turks of the ‘ Beatnik ‘ generation.

However the words ‘ anger ‘ and ‘beatnik’ do not occur anywhere in the two reviews, which suggests that both reviewers took Wilson’s book at face value; instead, despite his tender years ( which both reviewers marvelled at ) Wilson is treated as a serious philosophical writer. Here is Connolly:

‘ He (Wilson) has a quick, dry intelligence, a power of logical analysis which he applies to those states of consciousness which generally defy it. He has read prodigiously and digested what he has read…’

Toynbee feels the same about Wilson and his book:

‘It is an exhaustive and luminously intelligent study of a representative theme of our time…The Outsider remains a most impressive study of a kind which is too rare in England. French books of this kind are more familiar, but the fact that Mr Wilson is English gives him certain advantages over like-minded Frenchmen. He does not share their prevalent love of the elliptical and the paradoxical…’

Connolly is perhaps more generous than Toynbee regarding Wilson’s faults as a writer. He has ‘inaccuracies in quotations and titles, a general gracelessness and a hurried pontificating manner inclined to repetitions.’ Toynbee, in contrast, takes issue with some of Wilson’s rather dogmatic declarations regarding Aldous Huxley, Kafka, Sartre, Kierkegaard, Tolstoy and Dostoievsky. As for G. Bernard Shaw, Toynbee is amused to find that the playwright has been placed with Pascal and St Augustine as a ‘ religious thinker’.

Connolly also finds that in trying to find solace from the material world that his outsiders have rejected , Wilson is drawn to religion, he hasn’t compromised his intellectual perspective. Toynbee agrees. Wilson is determined to find a solution to the despair that modern society has produced through its adherence to the values of bourgeois existence, but that solution will only come through a ‘ new religious age ‘ born of intellect rather than the values of conventional organised religion.

Connolly ends his review with some advice to the reader: ‘ keep an eye on Mr Wilson, and hope his sanity, vitality and typewriter are spared’. Toynbee feels the same warmth towards Wilson, but with reservations. ‘ …clarity of analysis is certainly still needed, whatever may follow at last from that (but)… Mr Wilson’s book is a real contribution to our understanding of our deepest predicament.’

It is interesting to note of Philip Toynbee that in 1961, at a time when Tolkien was becoming a cult figure among the youth, he was brave enough to dismiss his work as an ‘ irrelevancy ‘. To him The Lord of the Rings and Tolkien’s other writings were dull, ill-written, whimsical and childish.’ [ R Healey]