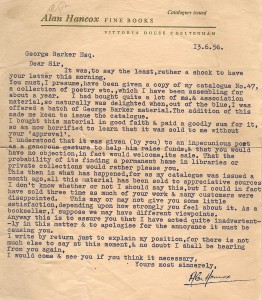

The bohemian poet George Barker could be quite vehement in his anger, especially when drunk, as he often was. In a letter written in June 1956 that we found in our archive here at Jot HQ he wrote angrily to the Cheltenham bookseller Alan Hancox complaining that some slim volumes of his poetry had been sold from his catalogue ‘ without his approval ‘. According to the unnamed ‘impecunious poet’ who had sold the books to Hancox, Barker had given them to him as an act of kindness to ‘ raise funds’ and had had no objection to their sale. This, it would seem, had been a fabrication and Hancox was then obliged to apologise for selling the books.

The bohemian poet George Barker could be quite vehement in his anger, especially when drunk, as he often was. In a letter written in June 1956 that we found in our archive here at Jot HQ he wrote angrily to the Cheltenham bookseller Alan Hancox complaining that some slim volumes of his poetry had been sold from his catalogue ‘ without his approval ‘. According to the unnamed ‘impecunious poet’ who had sold the books to Hancox, Barker had given them to him as an act of kindness to ‘ raise funds’ and had had no objection to their sale. This, it would seem, had been a fabrication and Hancox was then obliged to apologise for selling the books.

Knowing the egocentricity of Barker, the gift was probably made as a way of impressing the impecunious poet, who may have been unfamiliar with his work. If this is true, one can perhaps understand his hurt feelings. Throughout the ages older writers have sought to impress or influence their younger brethren by gifting them copies of their work. By so doing the donor hoped that in time this act of kindness would oblige this rising young talent him to repay the gesture by defending the reputation of the older writer. Sometimes it worked; sometimes it didn’t. In the case of Geoffrey Grigson and Wyndham Lewis, the mentorship (and possible gifts of books) lavished on the younger poet and journalist by Lewis in the ‘thirties reaped rich rewards for the artist and satirist twenty years later, when he had become totally out of fashion while Grigson was regarded as one of the most powerful influences in English letters. Although we don’t know who this impecunious poet was or when the gift of books was made, it is possible that at a time when Barker recognised that his reputation was beginning to nose-dive, he saw the poet as someone who could help him. Alternatively, the impecunious poet may have been one of Barker’s contemporaries , the alleged poet Paul Potts.

The embarrassment of Alan Hancox in all this was tangible from his letter. Booksellers depend on fair dealing, especially in the often lucrative field of modern firsts. Nevertheless, most dealers would have no alternative but to accept the word of a vendor, especially if that person was known to be a writer himself. In this particular case, if Hancox had had his number he could have rung up Barker to ascertain the truth of the matter, but he says nothing of this in his letter, and we must presume that he didn’t. It is possible that the incident crops up in Robert Fraser’s biography of Barker. Perhaps those in the Jottosphere can verify this.

Incidentally, on the subject of stolen books, there is a wonderful anecdote in Grigson’s Recollections(1984) concerning the ‘unemployable, persistent, rather squalid-looking’ Ruthven Todd who Grigson and his wife Bertschy had taken in to their home in Wildwood Terrace for ten shillings a week:

‘…a bookseller whose shop I frequented in Cecil Court …told me he had just bought ten shillings worth of books in one of which was a letter addressed to me. I was in that shop again some weeks later: the bookseller had bought more books –always ten shillings worth or thereabouts—from the same seller, in one of which this time was my signature, and the seller was—Ruthven Todd.

Between us we kept the arrangement operation for some time. Ruthven brought the books to Cecil Court, the bookseller paid him the required ten shillings. Ruthven with scrupulous regularity paid the ten shillings to my wife, and I went down to Cecil Court, and retrieved the books, for ten shillings…’

Interestingly, the reviewer of a recent biography of Todd (what would Grigson have thought of this?) refers to this anecdote in the current issue of the TLS.

R.M.Healey.

Writers do seem to have an egotistic attitude towards books and things they’ve given away: V.S. Naipaul was outraged when Paul Theroux sold presentation copies as part of a book clear-out and broke off relations and Theroux retaliated with a full and frank memoir of their encounters.

A poet I knew was very hurt when I replaced his individual volumes with a newly-published Collected Poems, because I didn’t need (or have room for) two copies of the books. Even the fact that I gave them to other people to persuade them of his virtues didn’t ease the pain.

I’ve held onto every book given me by an author. That said, I have sold books bought and inscribed at readings to booksellers. Of course, neither the booksellers nor the customers can tell that they weren’t gifts. I wonder if they think me ungrateful.

Thanks Brian/ thanks Roger. In my experience It is not hard to offend a poet .. Oddly it was I, CEO Jot101, who bought the books from VS Naipaul at his Wiltshire home. A charming man. I remember at the time asking him and his wife if Theroux would object to sale of books he had signed to them. VSN’s wife replied that he would probably not be bothered and might even send some more. Theroux, of course, got a book out of this perceived offense… Arise Sir Vidya!

The curious thing there is why VSN sold the books at all: unlike George Barker’s acquaintance he wouldn’t need the money and unlike me he had a large country house with lots of room for books. They do take a lot of dusting though.