The Complete Self-Educator (nd. but c1939), a copy of which we found in the archives at Jot HQ the other day, was one of those doorstep self-help books that Odhams brought out in the late thirties. We have already discussed various aspects of a companion volume in previous Jots. The Complete Self-Educator, however, is a different kind of multi-author book altogether and a much more challenging one. It sought to give the average intelligent reader a grounding in the principles of a number of important academic disciplines, including biology, medicine, physics, chemistry, economics, psychology, philosophy and logic.

Some of the writers were prominent experts in their field—people like Professor Erich Roll( psychology) and Max Black ( philosophy). Others, like Stephen Swingler, who later become a Labour minister, were relative newcomers who had published work in areas not altogether related to the subjects on which they were invited to write. One of these tyros was John Langdon- Davies, who had published books on Spain and women in society, but whose topic for the Complete Self- Educator was ‘The English Common People’.

Among the rather conventional fellow contributors Langdon-Davies stood out as a bit of a maverick. Born in Zululand, when it was part of South Africa, he came to England as a young boy and went on to attend Tonbridge School, which he hated. He was not, it must be said, officer cadet material. When he was called up in 1917 he declared himself a Conscientious Objector and as such served a short prison sentence. Declared unfit for military service, he lost two of the three scholarships for St John’s College Cambridge that he had gained at school. At Cambridge he tried to live off the remaining scholarship, but was obliged to abandon his studies. As a result, he switched his attention to the fields of archaeology and anthropology and ended up with diplomas in these disciplines. While an undergraduate Langdon-Davies did, however, manage to publish a volume of poems, The Dream Splendid, which received some favourable reviews.

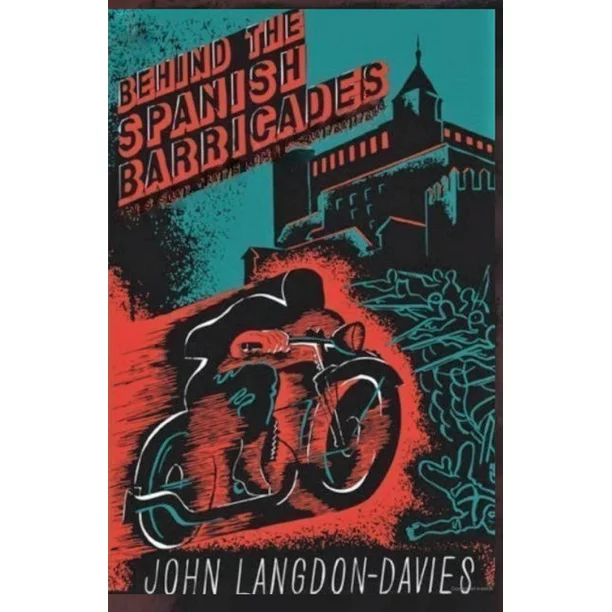

After the War Langdon-Davies embraced leftish politics, promoting the cause of women with his book A Short History of Women and embracing the anarchist cause in the Spanish Civil War with Behind the Spanish Barricades. His opposition to Nazism, fascism and ‘scientific racism’ can be gleaned from the opening paragraph of ‘The Story of the Common People’.

‘…English history is what it is because geography and geology made England what it is. We can go further than this, and say that geography and geology have made the Englishman himself what he is…’

The race or peculiar ‘ stock ‘ of the English, he argues, is irrelevant.

‘Racial theories of history put the emphasis of the superior qualities of some race , almost always the one to which the person expounding them belongs. We all know quite enough about Adolf Hitler’s theories of history; and an Englishman who believes that England is, must, and ought, to be superior to other countries is making exactly the same mistake as Hitler.’

Perhaps this is a dig at the popular historian Arthur Bryant, who in 1939 wrote a foreword to a new edition of Mein Kampf, praising Hitler. To the end Bryant retained a highly romanticised view of the English as a ‘race’.

In contrast, Langdon-Davies saw the English as ‘ mongrels ‘—the end product of a wave of invasions and conquests by various racial groups from all parts of Europe going back to the end of the Ice Age. Moreover, the English, Langdon-Davies argued, got their rich and complex culture from all these invaders:

‘ We English get our religion from the Jews, much of our philosophy from the Greeks, our literature largely from France and Italy, our law from Rome, and much of our science and medicine from Germany.’

Quite a claim, but not one that can be easily repudiated, especially if one bears in mind that many mathematical and scientific concepts originated in the Middle East but were filtered through European cultures.

As any Marxist might, Langdon-Davies saw the power struggle throughout the Middle Ages between the aristocracy and the monarch culminate in the death of feudalism and an increase in wealth through the rise of mercantilism and rural industries, such as weaving. In this way was established the leisured class under Elizabeth I.

‘Hitherto nobody had had much time; the rich were forever preparing for war, the poor had their faces ground into the soil; nothing could be more illiterate than a knight in the Age of Chivalry. But now people began to find time for cultivating their minds. This is why the Elizabethan Age was a ‘nest of singing birds ‘; poets, playwrights, artists, musicians had been given an audience by the coming industrial wealth and its results , a leisured class. Shakespeare could not have existed until industry had begun and feudalism been destroyed’.

Langdon-Davies went on to found the famous ‘Jackdaw’ series of educational aids and to write, under the pseudonym ‘John Stanhope’ ,The Cato Street Conspiracy,

where his radical political views are very much evident.

R. M. Healey