This eating place has undergone various transformations since its heyday in the nineteen thirties. In the mid fifties, when the following description was published by Fanny and Johnnie Cradock, it was the haunt of literary agents and publishers, among other types.

‘ As the Ivy restaurant is to the theatre, so Monseigneur’s is to that critical, cocktail of pedants, psychiatrists and introverts, the book publishers and the literary agents, the majority of whom are addicted to good food. A minority in our experience requires more of a wine than it is young and not corky. Only a fraction can distinguish between wines that have been fairly ordinarily handled and wines that have been cherished in the great tradition. For this reason the Monseigneur, where the food is never less than good and is sometimes more than very good, suits this brigade down to the socks. Signor Gualdi suffers from insufficient cellarage and keeps a relatively small stock of wines. Such as he keeps will serve you well—in their category, but his wine list does not soar vinously, as he will be the first to agree. Indeed, this courteous and experienced restaurateur soars above the only point of criticism to his own lasting success and the gratification of many contented diners. Among these, in other days, Signor Gualdi numbered the then Prince of Wales, who was particularly addicted to a house speciality of 1955, Choux Monsieur, a welcome and original addition to the hors d-oeuvre trolley. Equally agreeable is the house custom of a dish of the day, Silverside of Beef and Dumplings on Wednesday, Bouillabaisse on Fridays, are days in which we have interested ourselves profoundly. The coffee, too, is excellent, made on the proprietor’s remarkable little table Vesuvius at luncheon-time, when the restaurant seethes with custom and by night, when the tempo is suited to a more leisurely pattern of dining, which is pursued in great comfort.’

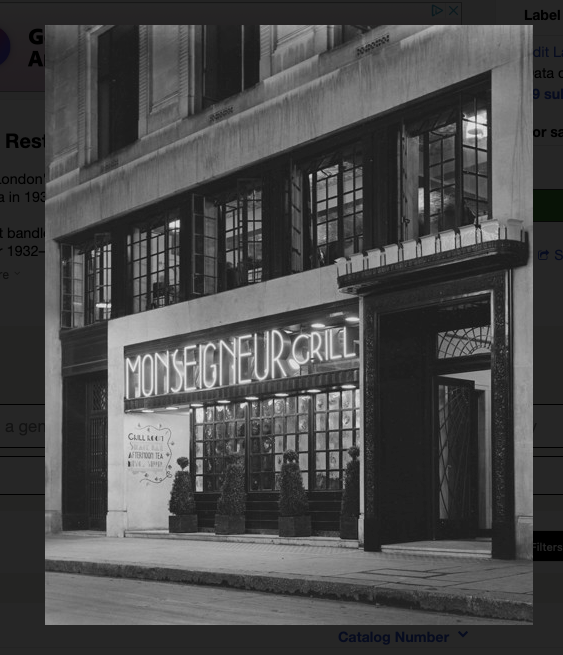

What the Cradocks omit to mention among their catty remarks on literary agents is that the Monseigneur Grill was a significant example of Art Décor design and internal décor. Certainly the RIBA seems to think so, as its archives contain a number of striking photographs showing the interior of the restaurant. Designed by architects William Henry White & Sons in 1931 and decorated by French decorators Marc-Henri and Laverdet ( who also designed the interior of the Whitehall Theatre in 1930 ) in a flamboyant style, its dining area was decidedly spacious, but lacked a certain intimacy.

In those early years it became a fashionable restaurant which allowed diners to watch a cabaret performance. It was also a hot spot for dance music: Reginald ( Roy) Fox and Lew Stone being the resident bandleaders here. A magazine illustration of c 1931 entitled ‘ The Monseigneur —London’s latest chic restaurant ‘ shows diners watching a cabaret from their tables, with the chef M. Taglioni standing among the diners to the right. According to a description of the scene, the restaurant ‘shared rival prominence with the Savoy restaurant or the Mayfair Hotel as the top showcases for the popular music of the day. It is probably at this time that ‘Bertie’ , then Prince of Wales, who later became Edward VIII, ate his favourite dessert, Choux Monsieur, which was still, according to the Cradocks, on the menu a quarter of a century later. The large size of the restaurant made it susceptible to conversion and indeed it became a cinema in 1934 A section of the original restaurant’s upper level formed a projection room, while the remaining level became a café which looked down on the auditorium, which preserved the original Art Deco design features. Today it is an African couscous restaurant, incorporating in the basement changing rooms of the former 1930s restaurant, the Jermyn Street Theatre.

As for that ‘critical cocktail of pedants, psychiatrists and introverts, the book publishers and the literary agents ‘ referred to by Fanny ( for surely it is she ), one can only guess. There were doubtless a few contenders in Soho, which is only a ten minute walk away from Jermyn Street, but probably more in and around Piccadilly. Johnson and Alcock, a literary agency which flourished in the fifties, had its HQ in Mayfair and that prince among literary agents of the time, David Higham, operated from Golden Square, just a five minute walk from Monseigneur’s. Jermyn Street was also the haunt of at least one famous author, Graham Greene, who drank regularly at the Red Lion ( still there) with his Secret Service pals. It’s true that Piccadilly wasn’t a celebrated home of publishers, most of whom were located in Bloomsbury or Covent Garden, but Hilary Rubinstein, who worked for Gollancz from 1950 – 63, and who later became a literary agent for A. P. Watt, could have been a diner at Monseigneur’s. The Gollancz office was in Covent Garden—a brisk twenty minute walk away—but publisher having almost single handedly invented the long lunch, along with BBC producers , time would not have been of the essence for Rubinstein, who was known to have been a bon viveur with a particular penchant for chocolate along with ‘ small owner-run hotels ‘.As someone who compiled the Good Hotel Guide and the Good Food Guide ( founded in 1951 by Raymond Postgate), he would perhaps have appreciated the uncomplicated and well cooked but homely fare offered by Signor Gualdi.

R. M. Healey