|

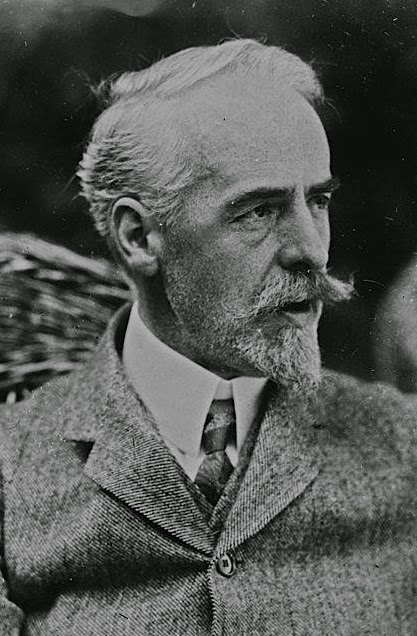

| Wickham Steed (Bibliotheque Nationale Francaise) |

[L.R. Reeve* writes:] Somewhere in the world of books there must surely be a biography of the late Wickham Steed. He would have been an eminent man if only for his vast knowledge of foreign languages: a knowledge which could be acquired only after months and years of intense application to his studies and excellent hours.

One wonders whether his obvious passion for other tongues began at the Sudbury Grammar School. Did he learn from an enthusiastic and efficient French teacher, or was his enthusiasm inborn in spite of an apathetic form master? No matter. His enthusiasm and obvious genius could never develop so remarkably without both inherent ability and uncommon will power. No indolent man could have achieved so much. His long arduous apprenticeship abroad began, I fancy, at the Sorbonne, in Paris. When he spoke to a large audience on foreign languages at Essex Hall, Strand, he told us of a Parisian who informed him that he spoke French like a Frenchman: a testimony which all students would like to hear.

Many English people obtain employment in foreign countries in order to reach a working knowledge of a certain tongue. A friend of mine served behind a counter in Paris; but most professional men of course aspire to a university, for it is there they learn the grammar, the correct accent, and study the refinements and culture of a beautiful language in a beautiful city. To be in Paris itself, is, I should think, an inspiration to study and learn as much as possible of an historic centre of learning, and as for its beauty on has only to examine a view from the top of Notre Dame to appreciate the genius of man to design and build a city carefully planned by architects of vision so long ago.

But I must get to Jena and Berlin. In the sixteenth century John Frederick the Magnanimous of Saxony nourished the question of a university among the narrow streets, old-fashioned houses and medieval market square of Jena. His three sons made the dream a reality. Hence Wickham Steed was enabled to go and study at the university economics, philosophy and history. It would be interesting to know which methods he adopted to learn the foreign languages. Did they vary in each country? He must have studied literary structure to write such publications as 'L'Angleterre et la Guerre' and 'L'Effort Anglais' ; but was his most rewarding harvest sown by conversations with great French scholars? and concerning his fluency in Italian my only source of information is the fact that for five years he was foreign correspondent of The Times at Rome.

But I must get to Jena and Berlin. In the sixteenth century John Frederick the Magnanimous of Saxony nourished the question of a university among the narrow streets, old-fashioned houses and medieval market square of Jena. His three sons made the dream a reality. Hence Wickham Steed was enabled to go and study at the university economics, philosophy and history. It would be interesting to know which methods he adopted to learn the foreign languages. Did they vary in each country? He must have studied literary structure to write such publications as 'L'Angleterre et la Guerre' and 'L'Effort Anglais' ; but was his most rewarding harvest sown by conversations with great French scholars? and concerning his fluency in Italian my only source of information is the fact that for five years he was foreign correspondent of The Times at Rome.

It is impossible to give even a brief account of his most exciting life without mentioning a few dates as quickly as possible. In 1896 he joined the staff of The Times as acting correspondent in Berlin. He was then 25 years of age. In 1897 he was correspondent of The Times in Rome for five years; then he spent eleven years at Vienna as correspondent for the same paper. In 1914 he was appointed foreign editor of The Times, and during World War I was mainly responsible for the foreign policy of the newspaper. Furthermore, during the war he was engaged in propaganda in enemy countries; and in March 1918 was head of an official mission to the Italian front, where he was authorised by Allied Governments to promise independence to the Habsburg peoples. In 1919 he became editor of The Times for three years (I argued with an inspector about this. He said the great journalist was never the editor). Then in 1923 Steed became proprietor and editor of the 'Review of Reviews' and during this period -until 1938- he was a lecturer on Central European History at King's College, Strand. In addition he commenced in 1937, a ten-year stint as broadcaster on World Affairs in the overseas service of B.B.C.

His publications? There must have been more than twenty-five books, some of which enjoyed three or more editions and some translated into foreign languages. An average man would have felt overworked in writings the volumes alone. Five of them I should choose immediately if I came across them individually in my public library: 'Through Thirty Years', 'Hitler: Whence and Whither', 'The Real Stanley Baldwin', 'Words on the Air', and 'The Press'. I rather fancy that difficult as I find it nowadays to concentrate on a bedside book -

Wickham Steed would act as my cup of coffee.

His appearance? He was the only man I have ever seen wearing a goatee beard who didn't arouse a slight irritation. It was skillfully clipped and somehow it suited Henry Wickham Steed. Apart from him I have always experienced a pathological dislike to the shape of such a facial decoration, although certain of my best friends will insist on the fashion which I suppose they think makes for the admiration of any onlooker. Then his suit. Was it my fancy, or did his general appearance make me think of a continental tailor? He was certainly well-dressed, perhaps a shade overdressed. Besides, a little above average height, and thin, he made an attractive, upright figure, to which was certainly added a very good speech, with few gestures, easily delivered and well received by a critical audience who would have enjoyed another ten minutes. All told his oratory was in the first class without reaching superlative heights; and I need not announce that there was no trace of the charming Suffolk dialect. I know some brilliant men and women who are proud to maintain their local tongue. Understandable, but not one of my aspirations. (An expert the other day told me he couldn't get my accent). I might mention too that I felt there was just a hint of arrogance in his general speech, just a tinge of aggression in his oration. Well, he had something to be arrogant about, and I believe he was honoured by several foreign and English decorations I should have enjoyed his magnificent lectures at King's College.

My greatest surprise at the Essex Hall meeting was that he was very critical of Esperanto. He declared that such an invention would gradually develop into a series of regional dialects. I wonder whether esperantists have discovered such a tendency. One enthusiast assures me that such a contingency is impossible.

The native inhabitants of Long Melford, Suffolk, must be proud of their distinguished son. I trust that a suitable memorial has been installed in an appropriate spot. I am sure he is on the Roll of Honour at the Sudbury grammar school.

* From Among those Present: Very Exceptional People by L.R. Reeve whose work is discussed at the previous posting on Nicholas Murray Butler.

I have a letter from Mr Steed, which I will publish soon on Jot 101. Watch this space