This is the second catalogue of rare books issued by G. F. Sims that we have reviewed in Jot 101.Sims was regarded as a particularly rara avis among dealers, principally because his catalogues were chock full of scarce and interesting items—not only printed books, many of which were signed and uncorrected proof copies, but manuscripts. In the eyes of some collectors these catalogues were worth collecting in themselves.

In this catalogue No. 79, seemingly dating from the early seventies, there are several delectable items, including a number of titles from the Fortune Press and many others containing inscriptions from the author. Some of Sims’ prices seem pretty reasonable today—so reasonable that we have taken the liberty of including the prices that they might fetch in 2025. However, one annoying feature of this particular catalogue is the absence of information regarding pagination. Most potential buyers would surely be interested to know how many pages an item contains. For instance, how long is The Atlantic Anthology? If one was shelling out £25 in 1972, this is critical information.

1) We should start with an author whose letter interleaved in the inscribed book boasts about the rising market value of this particular volume. The author is Paul Ableman and the book is I Hear Voices ( Olympic Press, Paris 1958). Today £8. 24p.

‘ …it is a first edition, and actually, I gather, it is acquiring slight bibliophile value—someone told me that on the NY second-hand market, it was fetching twenty-five bucks…’

Actually its rise in value ( if true) is genuinely surprising considering it had only been published fifteen or so years before. Ableman ( 1927 – 2006) was an experimental novelist who also wrote plays and specialised in that very modern genre, TV novelisations. He was responsible, for instance, for turning ‘Porridge’, ‘Dad’s Army’ and ‘Shoestring’, into novels. He also wrote non-fiction, including a rarish pamphlet which argued that feminism had betrayed its roots and had turned into an anti-men campaign. Ableman, by all accounts, led an extremely bohemian life in his Hampstead eyrie. His friend Margaret Drabble, who provided a preface for a reprint of I Hear Voices, painted a very amusing picture of life chez Ableman.

2) Christopher Whitfield, The Village and other poems ( Alcuin Press, 1928). No. 1 of 100 copies on handmade paper. £5.50. Today a signed copy is a small bargain at £36.

Whitfield ( 1902 – 67 ), a budding poet, migrated to Chipping Campden, possibly to be close to the town’s greatest resident, F. L. Griggs, the visionary etcher and Arts and Crafts champion, whom he befriended and helped during his later years. While there he kept a fascinating diary which was published by his son Paul in 2012. In his superb biography, F. L. Griggs, the Architecture of Dreams (1999) Jerrold Northrop Moore refers frequently to Whitfield and his diary, which was then unpublished. Griggs died in 1938 and Whitfield followed him twenty-nine years later.

3) Atlantic Anthology ( Fortune Press, 1945). Uncorrected proofs for the first edition. ‘This the publisher’s first page proof without the contributors’ names on the title page or the illustrations… Quite likely a unique state of this interesting anthology with contributions by Lawrence Durrell, John Peale Bishop, Henry Miller, Allen Tate and Wallace Stevens…’ £25. Today £57.

A pretty big price for this anthology, but Sims is probably right about its rarity. In contrast, the next Fortune Press item from Sims is A Fortune Anthology (n.d.), which contains contributions from at least three of those writing for the above, but is priced at just £5.

10) Light Blue Dark Blue (1960). First edition. Contributors include Ted Hughes, Dom Moraes and Sylvia Plath. £7.50. Today just £7.00, somewhat bizarrely.

Continue reading

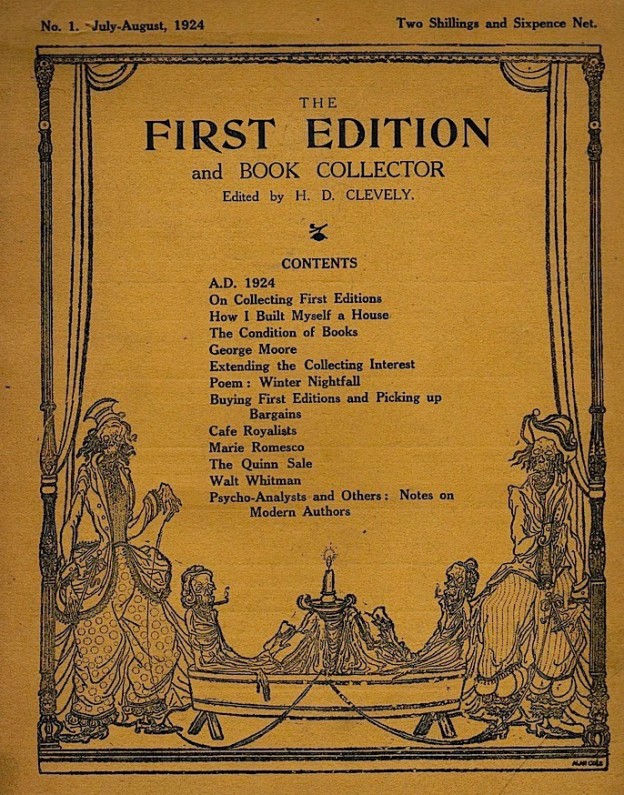

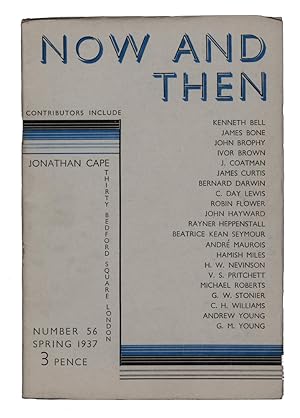

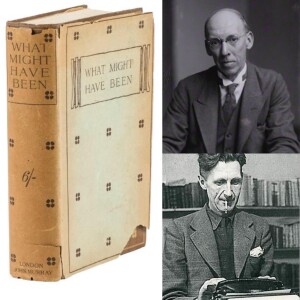

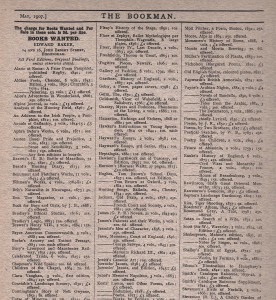

Before we report on the bargains available in May 1908 at Edward Baker’s Great Bookshop in John Bright Street, Birmingham (contrast it with Birmingham City Centre today, where there is not a single second hand bookshop ), let us examine what Mr Baker was prepared to give for top-end first editions in 1907 as advertised in The Bookman for May of that year.

Before we report on the bargains available in May 1908 at Edward Baker’s Great Bookshop in John Bright Street, Birmingham (contrast it with Birmingham City Centre today, where there is not a single second hand bookshop ), let us examine what Mr Baker was prepared to give for top-end first editions in 1907 as advertised in The Bookman for May of that year.