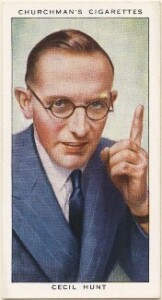

Cecil Hunt ( 1902 – 54) was a journalist, editor, novelist and anthologist best known throughout the English-speaking world for his compendiums of schoolboy ‘ howlers’. His first collection appeared in 1928 and proved to be a best-seller. At various times afterwards he produced other anthologies of howlers as well as guides to journalism, which he had studied at King’s College, London, and creative writing, books on the origins of words and a collection of unintentionally funny letters. He also wrote novels under two pseudonyms ( Robert Payne and John Devon). Interestingly, Hunt was President of the London Writers’ Circle and was instrumental in establishing Swanwick Writers’ Summer School. He died at just 51, but ironically his wife lived to be 107.

Cecil Hunt ( 1902 – 54) was a journalist, editor, novelist and anthologist best known throughout the English-speaking world for his compendiums of schoolboy ‘ howlers’. His first collection appeared in 1928 and proved to be a best-seller. At various times afterwards he produced other anthologies of howlers as well as guides to journalism, which he had studied at King’s College, London, and creative writing, books on the origins of words and a collection of unintentionally funny letters. He also wrote novels under two pseudonyms ( Robert Payne and John Devon). Interestingly, Hunt was President of the London Writers’ Circle and was instrumental in establishing Swanwick Writers’ Summer School. He died at just 51, but ironically his wife lived to be 107.

Hunt always denied the charge that he concocted many of the howlers that made him famous, explaining that there was no need to cheat, as ‘the genuine supply is ample ‘.

We must take him at his word, though reading some of the following examples from Science and Nature, taken from the second (1957) edition of My Favourite Howlers, it is sometimes easier to believe that they are product of a witty and inventive man rather than a ignorant schoolboy.

Science and Nature

The Solar System is a way of teaching singing

An herbaceous border is one who boards all the week and goes home on Saturdays and Sundays

Iron filings are always attracted by a magnate

An aorta is a man who makes very long speeches. Continue reading

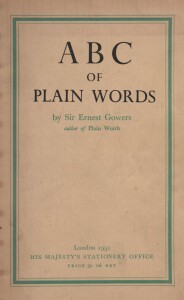

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.

When some BBC journalists don’t know the difference between reticent and reluctant, and use the word enormity to mean an enormous event, popular grammarians, such as Liz Truss or Ernest Gowers, who was her equivalent in the 1950s, are needed more than ever. That’s if these pisspoor journalists can be bothered to read their books.