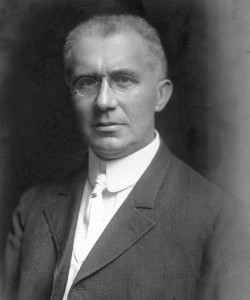

Found- a copy of Conclusions by Emile Berliner published in Philadelphia,  by the Levytype Co., in 1899. Berliner was the inventor of the gramophone and the gramophone record and exceedingly wealthy. This book presents his philosophy and may have been a vanity project, this copy is marked complimentary and limited to 500. He appears to have been something of an agnostic and his views, especially his faith in science,

by the Levytype Co., in 1899. Berliner was the inventor of the gramophone and the gramophone record and exceedingly wealthy. This book presents his philosophy and may have been a vanity project, this copy is marked complimentary and limited to 500. He appears to have been something of an agnostic and his views, especially his faith in science,

are somewhat ahead of his time:

On the Doctrine of Immortality

The confident belief of mankind in a personal immortality is a positive drawback to human progress.

The possibilities of earthly happiness are so vast, the dread of early death so natural and pronounced, that if mankind would but rationally divorce itself from its over-confidence in a life hereafter, it would work out its earthly Salvation in a very short time.

The time will undoubtedly come when most people will live to a hale old age, when they will be free from the hypocrisy, the intolerance, and the morbidness of our so-called civilisation, when food will be pure, when sound sanitary science by universally recognised, when life will be simple and free from sham, when love, in all its phases, will be less restrained, and when all parents will know that their children are and will be the incarnation of their combined thoughts and impressions.

Then, having tasted life from an overflowing cup, and having drunk the last drop at a ripe old age, man will gradually have become wearied and tired, and will be glad to lie down, expecting nothing, and leaving the future in serene resignation to take care of itself.

Prayer

The futility of prayer was never better emphasised than at the time of Garfield’s sickness and death, when some hundred millions of people earnestly and sincerely prayed for his recovery. What an absence of mercy!

But had Garfield been shot twenty years later Science would probably have saved him, prayers or no prayers.

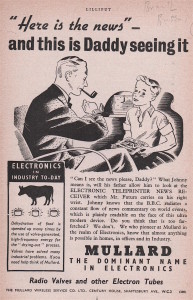

Discovered in a July 1930 issue of Armchair Science, an article by the magazine’s ‘technical advisor’ A. M. Low entitled ‘Little Things and Big Minds’. In it Professor Low argues that we shouldn’t be impressed by large things—whether they are exaggerated claims for some patent medicine, or some mechanical apparatus, such as a typewriter. Machines are made from small parts, just as matter is composed of atoms and molecules; and big phenomena, such as broadcasting is powered by electricity, which is a flow of electrons. Small is beautiful, in other words.

Discovered in a July 1930 issue of Armchair Science, an article by the magazine’s ‘technical advisor’ A. M. Low entitled ‘Little Things and Big Minds’. In it Professor Low argues that we shouldn’t be impressed by large things—whether they are exaggerated claims for some patent medicine, or some mechanical apparatus, such as a typewriter. Machines are made from small parts, just as matter is composed of atoms and molecules; and big phenomena, such as broadcasting is powered by electricity, which is a flow of electrons. Small is beautiful, in other words.

by the Levytype Co., in 1899. Berliner was the inventor of the gramophone and the gramophone record and exceedingly wealthy. This book presents his philosophy and may have been a vanity project, this copy is marked complimentary and limited to 500. He appears to have been something of an agnostic and his views, especially his faith in science,

by the Levytype Co., in 1899. Berliner was the inventor of the gramophone and the gramophone record and exceedingly wealthy. This book presents his philosophy and may have been a vanity project, this copy is marked complimentary and limited to 500. He appears to have been something of an agnostic and his views, especially his faith in science,