Chester Carlson (thanks Xerox)

‘ Who invented the photocopier ?’ is a question that sometimes comes up in pub quizzes. The answer, of course, is Chester Carlson, an American inventor whose persistence over decades made him a multimillionaire. This is not the place to survey Carlson’s brilliant idea, which transformed businesses all over the world. Instead, let’s examine a possible rival to xerography, as Carlson’s invention came to be called. This was ‘ electronographic ‘ or ‘ ghost printing, whose origins go back further than xerography.

We at Jot HQ must confess that electronography is a new term for us. But let the American journalist C. Lester Walker, who tried to explain the process in an article for Harper’s Magazine in July 1948, an extract from which we found typed up in our archives. Up to now, Walker begins, printing has been the dominant method of creating multiple copies of a text. But printing involves the application of pressure. With electronography:

…There will be no contact between the printing surface and the paper. Instead, a stream of electrons will supply the force needed to make the ‘ impression’.

Walker then goes on to tell us how this radical new process was discovered. It was all down to a boffin in the printing industry, William C. Huebner, who in 1924 discovered the process by ‘accident’.

He was called in by a printing house, which was doing a big-sheet label job, to help them stop what the printers called ‘ off-setting’…This day solid reds were offsetting badly, and Huebner was inspecting the stacked sheets by ‘ lift fanning’ the corners, when suddenly he saw something his eyes refused to believe. When he lift fanned (i.e.) ruffled the corners, the off-setting increased. That is, the red on the back of a sheet strengthened and deepened.

Huebner said to a pressman, ‘ You, look. Am I seeing things? The pressman said no—he thought he saw it too. Wondering if the offsetting could possibly be due to static electricity, Huebner arranged for a ‘ grounding’ of the press. The offsetting was checked. Then the static was pulling ink off one sheet ad depositing it on another ?

Huebner’s inventor’s mind started whirring. Before the end of that day, he had said, he had proved to himself that statically charged surfaces would make printing jump a gap as much as an inch wide. Nowadays he demonstrates this phenomenon to sceptics by rubbing by rubbing a sheet of celluloid with a handkerchief, laying a sheet of yellow copy paper over the celluloid, and then moving an ink-wetted artist’s paint brush around above. Ink flies from the brush to the paper two or three inches through space…

Walker goes on to explain how the process actually ‘ prints ‘:

There is an inking cylinder, a cylinder on which is the curved plate of type and a cylinder around the paper travels. The first cylinder touches the second and inks the type. But as the type cylinder and the paper cylinder rotate, they never touch. Between then stands permanently a narrow gap—usually from one to three thousands of an inch. Inside the paper-carrying cylinder is a gadget with electrodes, which runs the cylinder’s length and lies directly opposite the type cylinder outside. When current is turned on , this gadget produces a stream of electrons which pull the ink off the type cylinder and onto the paper. Another electrical circuit has already ionized and charged the ink negatively and charged the paper surface positively. When the machine is in operation, it has been observed, the ink on the type cylinder actually bulges towards the paper surface , and the paper surface moves towards the inked type cylinder. But turn off the ionizing current and keep the press running and mo print occurs, because no pressure content is present anywhere.

Continue reading

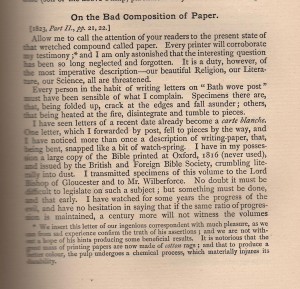

Researchers in newspaper and magazine archives often complain about the horrendous quality of newsprint they encounter. Sometimes whole pages are brown and need to be handled with extraordinary care as they are turned, lest they crumble to dust— to the embarrassment of the researcher. The decline of paper quality seems to have begun towards the end of the nineteenth century and is attributed to the high acid content of the wood pulp used for printing cheap publications—mainly newspapers and periodicals, particularly adventure and school stories for boys, but also mass produced books issued in serial form. The decay of newsprint appears to accelerate with exposure to sunlight, which explains why single issues of newspapers and magazines are much more likely to turn brown and crumble than bound volumes.

Researchers in newspaper and magazine archives often complain about the horrendous quality of newsprint they encounter. Sometimes whole pages are brown and need to be handled with extraordinary care as they are turned, lest they crumble to dust— to the embarrassment of the researcher. The decline of paper quality seems to have begun towards the end of the nineteenth century and is attributed to the high acid content of the wood pulp used for printing cheap publications—mainly newspapers and periodicals, particularly adventure and school stories for boys, but also mass produced books issued in serial form. The decay of newsprint appears to accelerate with exposure to sunlight, which explains why single issues of newspapers and magazines are much more likely to turn brown and crumble than bound volumes.