Researchers in newspaper and magazine archives often complain about the horrendous quality of newsprint they encounter. Sometimes whole pages are brown and need to be handled with extraordinary care as they are turned, lest they crumble to dust— to the embarrassment of the researcher. The decline of paper quality seems to have begun towards the end of the nineteenth century and is attributed to the high acid content of the wood pulp used for printing cheap publications—mainly newspapers and periodicals, particularly adventure and school stories for boys, but also mass produced books issued in serial form. The decay of newsprint appears to accelerate with exposure to sunlight, which explains why single issues of newspapers and magazines are much more likely to turn brown and crumble than bound volumes.

Researchers in newspaper and magazine archives often complain about the horrendous quality of newsprint they encounter. Sometimes whole pages are brown and need to be handled with extraordinary care as they are turned, lest they crumble to dust— to the embarrassment of the researcher. The decline of paper quality seems to have begun towards the end of the nineteenth century and is attributed to the high acid content of the wood pulp used for printing cheap publications—mainly newspapers and periodicals, particularly adventure and school stories for boys, but also mass produced books issued in serial form. The decay of newsprint appears to accelerate with exposure to sunlight, which explains why single issues of newspapers and magazines are much more likely to turn brown and crumble than bound volumes.

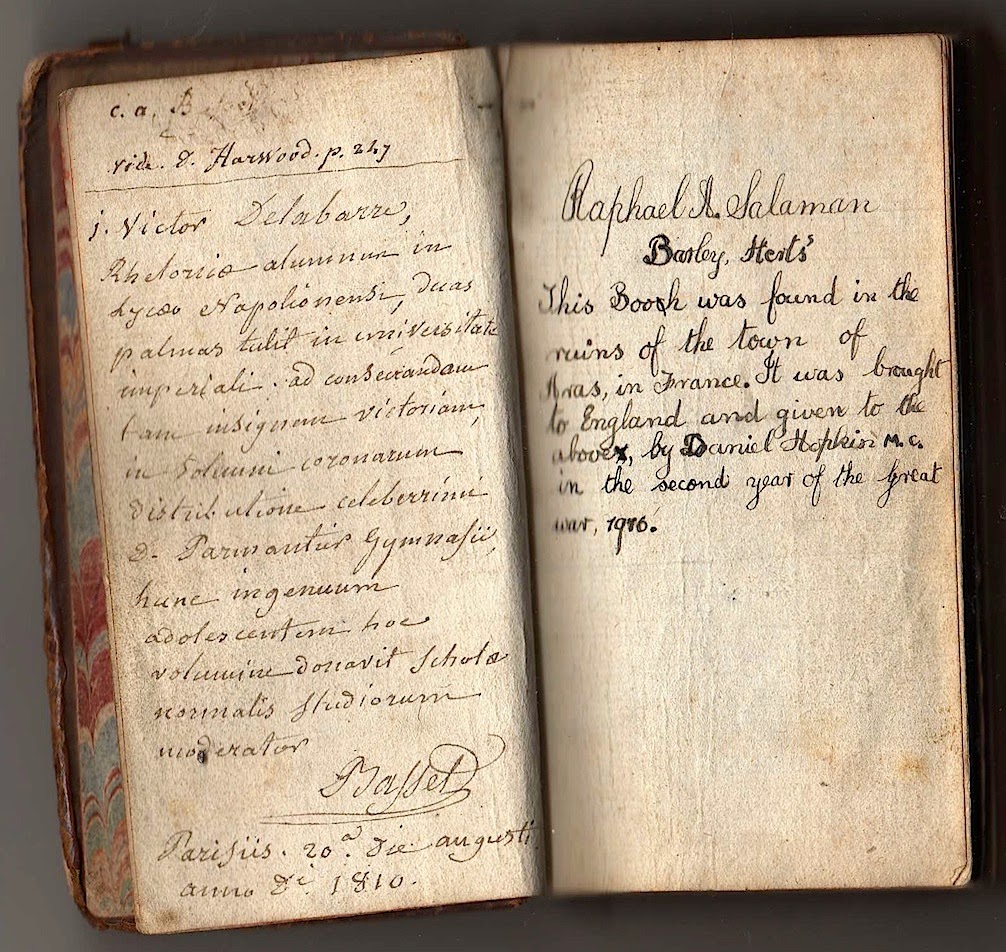

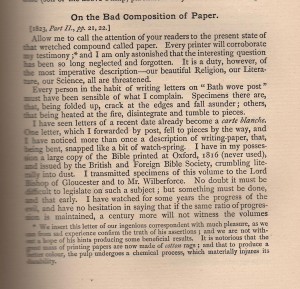

The quality of cheap paper in the early nineteenth century could also be poor, depending usually on the type of publication. The paper used for popular magazines and cheap editions of books was likely to be of less quality than that used for fashionable three- decker novels, new poetry and books of travels, for instance. It may also be true that before the universal penny post was introduced in 1840 the paper used for letters was of lesser quality and also made deliberately lightweight to save on postage costs. This may explain why the letter referred to in this extraordinary communication to the Gentleman’s Magazinein 1823 tore so easily. The other references to paper quality and printing ink in this article, however, are surprisingly to anyone with a knowledge of book history. Particularly fascinating are the scientific explanations as to why the quality of some paper in this period was so compromised. Continue reading