We have seen in a previous Jot how in The Writer magazine Compton Mackenzie told readers about his writing methods. Inspired by this article, the prolific novelist, anarchist, anti-imperialist and pacifist Ethel Mannin (1900 – 84) offered an account in the same magazine of her own working life.

She begins her piece by declaring that she dislikes dictating her work to another person. It’s too much like ‘undressing in public ‘. Dictating machines were around in her time, so it’s odd that she doesn’t mention these. Nevertheless, she admits to preferring to see her words on paper in the form of typing, mainly because she has difficulties on deciphering her own writing. She continues:

‘ In the twenties, when I was a young writer, I liked to emulate Arnold Bennett and keep office hours for work, and for a number of years I did so…, keeping to the 9.30 -6 working day I had know during my four years of office experience. But in those days life was different. Then I was a young married woman with a baby, a resident servant and a husband coming home at seven each evening. By the thirties I was on my own and living a quite different kind of life. A good deal of it was lived in hotels and pensions all over Europe, but still I tried to keep to a regular working day, though the hours began to be more flexible. I hardly know at what point in the forties I turned into the night worker I now inveterately am. Life changed again; resident domestic helped was replaced by daily women two or three times a week—an arrangement by this time , with an increasing liking for solitariness, I much prefer…I live alone—and like it.

The routine now is that I get into the study between ten and eleven in the mornings and am very often still there at midnight. Most of the day until six in the evening in occupied with mail ( like Sir Compton Mackenzie, I deal with about 4,000 letters a year ); then there are six clear hours till midnight for the book I am working on. I seldom continue much after midnight, feeling too mentally tired by then, though not sleepy. I doubt if it is possible to work for more than five or six hours out of the twenty-four on actual writing. On the days when the mail is less I start work—the actual writing, that is—in the afternoon, but then perhaps a guest is coming or supper and I must finish by seven or eight. Even so, I have been eight hours at the typewriter—a full working judges by non-literary standards. Leaving the study around midnight, I read for a while in bed and my bedside light is seldom out before 1 a.m.—often later…

Continue reading

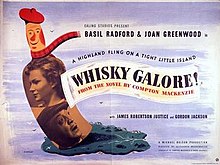

Compton Mackenzie is not a writer who raises much interest among readers nowadays. Few literary people today could name more than two of his many novels, the most famous of which, Whiskey Galore, was made into a hit film. However, back in the early fifties, readers of his article, Tricks of the Trade ‘, which appeared in the January 1953 issue of The Writer, would have lapped up this very frank account of his daily writing routine, which retains its interest today.

Compton Mackenzie is not a writer who raises much interest among readers nowadays. Few literary people today could name more than two of his many novels, the most famous of which, Whiskey Galore, was made into a hit film. However, back in the early fifties, readers of his article, Tricks of the Trade ‘, which appeared in the January 1953 issue of The Writer, would have lapped up this very frank account of his daily writing routine, which retains its interest today.