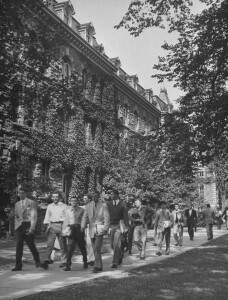

Writing in the Spring 1952 issue of New Phineas, the magazine of University College, London, Gordon Snow, who spent a year at Cornell (above), was pleasantly surprised at what he found there.

The academic syllabus.

My first impression…was one of surprise at the liberty and freedom which the students were given in choosing their courses; it seemed as if there was none of the overspecialisation that some of the honours courses in England tend to fall into…Second impressions, however, revealed that defects did exist in the system; many of the arts courses are run to cater in part for agriculture or science or hotel-school students, who have to fulfil a certain number of requirements in the liberal arts, and , who consequently, may have an interest in the theory of a liberal education but very little enthusiasm in practice for their particular requirements. As a result, there is not a great deal of homogeneity in purpose, or interest in the very large arts lecture classes , and many of the students who have come to college for vocational training pure and simple find the arts courses irksome. Since there students may be as much of two-thirds of the class, the lectures have to be scaled down to their needs: hence the universal and horrifying use of enormous anthologies for particular periods of literature, expensive as all American books are, and with up to 1,400 pages in double columns of fine print. My own anthology consists of representative selections from American poetry and prose, from Captain John Smith to Ernest Hemingway, and the lecture has to eat his way at high pressure, through major and minor writers, three times a week, making his own selections for his students from among the selections in the book, and to a large extent predigesting critical reactions to them. Independent thought is not inhibited my this method of teaching, since I have come across many examples of it already, but it can scarcely said to be encouraged. To this extent, and to the extent that they continue a no-specialised study of several subjects, American colleges are a smooth continuation of the high schools and their methods; the students are given a very thorough grounding in he subjects taken at English grammar schools , wit the benefit of the maturer mind which the college student brings to them, and since there are as many Americans who go to college —or at lead begin college—as reach the Sixth Form of English schools, the universities here serve their purpose, a very different one from the English universities, well enough…

In strange combination with the social sophistication which distinguishes the American student, there is a remarkable intellectual naivete—even among the graduates, who are generally equivalent in critical ability, if not in a specialised knowledge, to their English counterparts. Admittedly the case of a student majoring in English, who, hearing that I had also taken English honours, approached me and asked “ what I thought of Shakespeare “, is an exceptional one ; and I have been lucky enough not to encounter that caricature of the American college girl, current in Oxford small talk, who is supposed to ask earnestly: “ D’you b’lieve in Gahd ?” . Yet, however lax their social morals are supposed to be, their literary morals are absolutely Puritan. It is almost impossible top be flippant about any author with a famous name, deserved or not; Stephen Potter’s Rikling gambit has no effect over here; and indeed, to use any of the standard Lifemanship ploys to make the conversation less serious is merely to beat the empty air. Even a dismissal such as, “ Oh, nobody reads Kipling any more “ , is greeted with cautious and serious consideration.

The social environment

…The fraternity houses, supposedly very strong on this particular college campus, are another remarkable part of university life in America. They serve somewhat the same social function as colleges in Oxford and Cambridge, except that a homogeneous selection is made by the existing members instead of the college faculty, and that the selections are made more from the point of view of social potentialities than intellectual…,they serve to bring together a group of 30 – 50 students, usually congenial to each other, but studying different subjects, and to give them a social centre , a four-year acquaintance with their fellow –members, out of the bewildering mass of students at the university—and a handsome house with a spacious lounge, for leisurely conversation over after-dinner coffee , not so leisurely poker-tables, and far-from-leisurely weekend parties. The members wander informally in and out of each other’s rooms and’ borrow’ each other’s records, gramophones and typewriters—it is impossible to “ sports one’s oak “ as at Oxford ; but on the other hand there is no desire to do so…The houses are run by the students themselves, who hire a cook, a handyman, and student waiters…

Perhaps the only real objectionable feature of fraternity house life is the inefficient methods by which they select their new members; it is largely this that has led to their abolition at Harvard, Yale and Princeton…During the first two weeks of term, the freshmen who look promising, who have good high school sports records, who are “ legacies “ from alumni, or whose fathers were at the same fraternity, are invited in relays to lunch or dinner, and are interviewed in their lodgings or dormitories during the rigidly limited “ contact periods “. Then the fraternity men hold meetings to discuss each freshman they are “ rushing “ ; some are “ dinged “ or rejected; others are invited to further meals or more sizing-up, until towards the end of the fortnight thee numbers have been reduced to a manageable figure and the arguments over the merits of the freshmen become increasingly heated and raucous, some of the meetings continuing until 3 a.m. This procedure goes on in over 50 fraternities at Cornell; some men are not “ rushed “ at all; others are “ rushed “ by several houses, and there is some tension in the air as the freshmen are shown about the house—the cosy bar, the panelled library that looks like a miniature St James’s club, the candle-lit dining room—and attempts are made on both sides to impress and attract the other. Finally, bids are made to the last remaining men being “ rushed “ , and those who accept become pledges of the house, and in the following term initiated brothers of the house. Initiation is no longer the dangerous procedure it was some ears ago; the occurrence of serious injuries led to the university’s forbidding of the riskier form of “ hazing “ , as the endurance test was called . Until the new class arrives, however, the freshman class has to fag for the other members, answering the telephone, fetching messages, and so on. [RR]