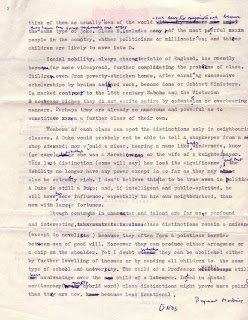

A typed signed manuscript with ink corrections by Raymond Mortimer and a typed signed letter of rejection from the then Sunday Times editor Harold Evans.

Mortimer's article is now somewhat outdated, although a class system still exists in Britain. 'The Nobility' has now been largely replaced by celebrities and there is now, as in America, a much greater emphasis on money. It seems at the time the Sunday Times was running a series of articles on class by well known writers.

April 18th, 1969

Mr. Raymond Mortimer, CBE,

5 Canonbury Place,

LONDON N.1.

Dear Raymond,

I'm sorry that I agree with you that I don't think it is quite pointed enough. I think it would need to have some specific symbols of class. The Snowdon observation about class and motoring is the sort of thing I mean:

Saloon car with two husbands in front, their two wives behind = lower class.

Ditto with mixed couples in front and back = middle class.

Ditto with no one in back, husband and somebody elses wife in front = upper class.

I leave it to you whether you feel you want to do any more work - I'm sure there is a piece here - and I'm grateful for you response. Your sincerely Harold Evans. Editor.

[Mortimer article] "Why, " I was asked by a friend half my age, "Do you say that there are at least nine classes in England?" Well, I also denied the existence of any frontiers between them, and it might be nearer the mark to say eighteen, because each class can roughly be divided into those who were born in it and those who were not. The subject in any case has become a joke and an embarrassment, as sex was in the Victorian Age. We avert our eyes when class "rears its ugly head"-- and may even believe that distinctions of class no longer exist, apart from differences in education, occupation and income. This seems to me wishful thinking, although the young today are not nearly so class-conscious as their grandparents.

The various classes are difficult to define or enumerate, because they often depend upon social habits-- tastes in food, drink, dress and pastimes, for instance, and ways of speech, both in vocabulary and accent. The ninefold division (derived from social historians, biographers and novelists, not from sociologists,) cannot be trusted because it is mainly based upon rank or occupation. All reserves made, here are the nine. A. Royalty; B. The Nobility; C. The Landed Gentry; D. The Upper Middle class; E. The Solid Middle Class. F; White-collared workers. G. Lower Middle Class (small shopkeepers, for instance); H. Skilled Workers; I. Unskilled Workers. (That use of the words "worker" or "working class" is unhappy, because it implies that other classes are idle.) Each of these classes merges into others.

Members of A. marry into B., C, or even D. English peers always have ancestors from other classes, and most of their descendants do not rank as noble. D. and E. are even more indefinable, because each includes many members of what used to be thought separate classes, the Professional and the Commercial. Soldiers, clergymen, Civil Servants, doctors etc. used to think themselves a cut above businessmen; but now neither type of occupation decides a man's class. Members of D. retain great influence -- expect in politics and industry- and are often denounced as "the old boys' network" (although not identical with what is now called "the Establishment). They recognize their fellows at once, and think of them usually "men of the world" and easy to negotiate with because they have the same manners and enjoy the same type of joke. Class E, includes many of the most powerful people in the country, whether politicians of millionaires; and their children are likely to move into D.

Social mobility, always characteristic of England, has recently become far more widespread, further complicating the problems of class. Children even from poverty-stricken homes, after earning successive scholarships by brains and hard work, become dons or Cabinet Ministers. In marked contrast to the 18th century Nabobs and the Victorian nouveaux riches they do not excite satire by ostentation or overbearing manners. Perhaps they are already so numerous and powerful as to constitute a further class of their own.

Members of each class can spot the distinctions only in neighbouring classes. A Duke would probably not be able to tell a shopkeeper from a shop steward; nor would a miner, hearing a name like Lady Windermere, know (or care) whether she was a Marchioness or the wife of a knighted mayor. This last distinction (some will say) has lost its significance, and that the Nobility no longer have any power except in so far as they may also be extremely rich. I don't believe this to be true even in politics. A Duke is still a Duke; and, if intelligent and public-spirited, he will have far more influence, especially in his own neighbourhood, than men with larger fortunes.

Though contracts in character and talent are far more profound and interesting, class distinctions remain a nuisance (except to novelists) because they often form a pointless barrier between men of good will. Moreover they can produce either arrogance or a chip on the shoulder. Yet I doubt whether they can be abolished either by further leveling of incomes or by sending all children to the same type of school and university. The child of a Professor would still have an advantage over the child of a labourer. Indeed in a total meritocracy (nasty hybrid word) class distinctions might prove more painful than they are now, because less irrational.

Raymond Mortimer