Another Jot from the loyal RH, scholar, idler, gent and swordsman. The book mentioned is a signed book of mathematics (sort of) from 1775 and not in the British Library but obtainable online as we speak, signed by the author, for a paltry $50.

A Scottish Seal of Approval

Remember those Edwardian newspaper ads for Dr Collis Browne’s ‘Chlorodyne’—a patent medicine that purported to clear up cholera and diarrhoea, but which would certainly not cure the former, as it contained mainly laudanum and tincture of cannabis, both of which, incidentally, would be banned today. Every bottle had Browne’s printed signature on it. Going a little further back, each label for Warren’s patent boot blacking bore the printed signature of its manufacturer, a fact to which the teenage Charles Dickens, whose job in 1824 involved sticking these labels onto the pots, could attest .

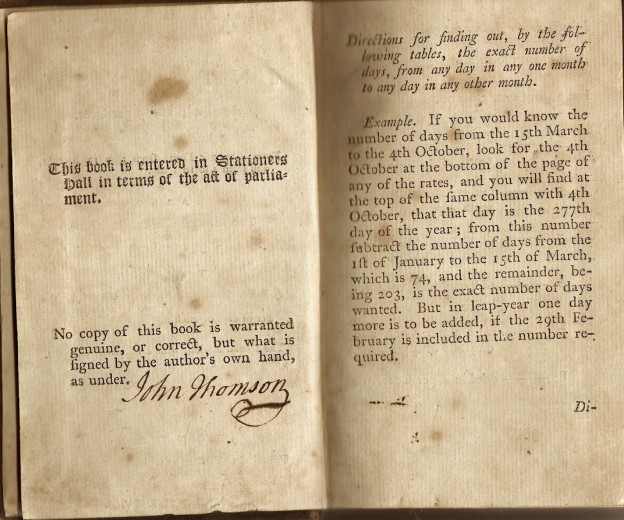

I cannot recall any grocery or pharmaceutical product that bore the manufacturer’s signature before the days of Warren, but I might be wrong. Robert Warren was a marketing pioneer (as John Strachan’s excellent study, Advertising and Satirical Culture in the Romantic Period, discusses at some length). But look in vain in Strachan for books of the Romantic period that bore the author’s printed signature. As for a handwritten signature, I’ve come across none whatsoever. You have to go back to the Age of Johnson to find just one example. The second edition of Tables of Interest at 4, 4 1/2 and 5 per cent, which Cadell and Murray bought out in 1775 warns the buyer on page two not to accept any book bearing Mr Thomson’s name on the title page that does not also feature his actual signature. So there it is, written in ink, at the bottom of page two. Amazing !

The reason for all this wariness must have something to do with the frequent acts of book piracy that prevailed before the Copyright Act was passed in 1842. It would seem that the first edition of Mr Thomson’s book had been a victim of piracy soon after it had appeared in Edinburgh in 1768.Book piracy in the 1760s seems to have been particularly prevalent. My own edition of Pope’s Works, which came out a year earlier, was a pirated edition by A. Donaldson, a notorious offender from Scotland, who may have been the culprit in the case of Thomson’s Tables.