Writers of all kinds should be grateful for the work done of their behalf by two men, the lawyer, MP, and writer, Thomas Noon Talfourd (1795 – 1854) and the Tory MP and historian Lord Mahon (1805 – 75), who were the driving forces behind the Literary Copyright Act of 1842. But this was not the first Act that granted authors rights over their work. The first to do so became law in 1709. Up to this time copyright was restricted to booksellers who, as publishers, would buy up all rights from authors for a fixed sum. The 1709 Act first made it legal to anyone to own a copyright—even authors, although it gave them a meagre fourteen years. A further Act of 1790 extended this period to 28 years. Although this was an improvement, it still meant that a young writer like Dickens, whose Pickwick Papers was dedicated to Talfourd in 1837, could not expect to profit from his early works beyond his mid fifties. It is probable that his friendship with the novelist prompted Talfourd to pursue legislation that would benefit writers like him and to this end he presented an initial version of the 1842 bill to Parliament in 1837.

This bill failed, but Talfourd remained determined. Further bills were presented and at last, in 1842, the Literary Copyright Act became law. This extended copyright to the life of the author plus seven years, and where copyright already existed in a work under earlier legislation, it was to be extended to that provided by the new Act. The Act was further amended in 1911 and several times since.

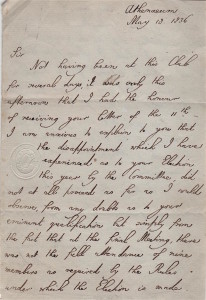

So here is a rather rare item –a letter from Lord Mahon to T. N. Talfourd written six years before the famous Act was passed. Although the issue of copyright is not mentioned in the letter, the contents do suggest that the two men, who shared literary interests, were on friendly terms. Talfourd had sought election to the Athenaeum, a prestigious London club which numbered many writers, artists and scientists among its members. He was unsuccessful on this occasion, not because, as Mahon explains, the committee doubted Talfourd’s ‘eminent qualification ‘, but because there were insufficient committee members present to vote.

Although Talfourd’s literary career was unremarkable, he became a guiding presence on the Bench and died at the comparatively early age of 59 while delivering judgement in court. [R.M.Healey]