Bishop Bury of Durham spent so much money on books that he lived in dire poverty and debt and when he died all that could be found to cover his corpse was some underwear belonging to his servant.

Bishop Bury of Durham spent so much money on books that he lived in dire poverty and debt and when he died all that could be found to cover his corpse was some underwear belonging to his servant.

The facts regarding his library are mind blowing. According to W.M. Dickie, who wrote a paper on Bury and his magnum opus , the Philobiblon, in The Book Handbook (1949), he had more books than any bishop in England. Five wagons carried them away, which suggests that the number of volumes was more than 1,500. This compares with the Sorbonne’s 1,722 in 1338, the 380 volumes at Peterhouse College, Cambridge, in 1418 and the 122 housed in the University Library there in 1424.

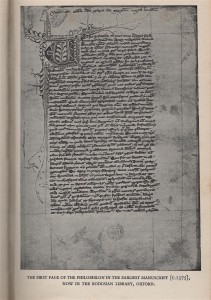

In his Philobiblon Bury writes of wishing to found a college in Oxford and to endow it with his library, but no college is named. Some historians have maintained that the library was bequeathed to Durham College, but there is no evidence that the college received any such endowment. The sad truth is that this wonderful library was probably broken up and sold off to pay Bury’s huge debts.

The Philobiblion is revealing as to how many of Bury’s books were acquired:

“We were reported to burn with such desire for books, especially for old ones, that it was more easy for any man to gain our favour by means of books than of money. Wherefore since support by the goodness of the aforesaid Prince (Edward III)…we were able to requite a man, well or ill, to benefit or injure mightily great as well as small, there flowed in instead of presents and guerdons, and instead of gifts and jewels, soiled tracts and battered codices, gladsome alike to our eye and heart…In good will we strove so to forward their affairs ( the affairs of donors of books) that gain accrued to them, while justice suffered no disparagement”

In this way Bury, when Keeper of the Privy Seal, was given four books, namely Terence, Vergil, Quintilian and Jerome against Rufinus by Richard de Wallingford, Abbot of St Albans, who also sold to Bury for fifty pounds of silver, thirty-two other books, of which he gave fifteen to the refectory and ten to the kitchen (presumably at Westminster Abbey), an act which was later condemned by Thomas Walsingham, former scriptorarius at the Abbey. The Abbot’s motivation in securing such an astonishing bargain for Bury was to promote the interests of his monastery at Court and indeed Bury helped him secure a royal charter giving the Abbot the exceptional right of imprisoning excommunicated persons. When Bury became Bishop of Durham in a fit of remorse he restored some of the books to St Albans. And following his death, Wallingford’s successor at the Abbey secured other volumes at a discounted price from Bury’s executors. One of these, John of Salisbury’s Policraticus—now in the British Museum—bears an inscription recording its sale to Bury and its repurchase in 1346 from his executors. Only two other manuscripts are known to have belonged to Bury. One is in the British Museum and the other is in the Bodleian. Both are from St Albans.

The Philobiblion itself remains a hymn to the value of books as guides and comforters.

They are masters who instruct us without rod or ferrule, without angry words…If you come to them they are not asleep; if you ask and inquire of them, they do not withdraw themselves; they do not chide if you make mistakes; they do not laugh at you if you are ignorant.

Bury scoured Britain and Europe to build up his library:

We secured the acquaintance of stationers and booksellers, not only in our own country, but of those spread over the realms of France, Germany and Italy, money flying forth in abundance to anticipate their demands; nor were they hindered by any distance or by the fury of the seas, or by the lack of means for their expenses, from sending or bringing to us the books that we required. For they well knew that their expectations of our bounty would not be defrauded, but that ample repayment with usury was to be found with us. No dearness of price ought to hinder a man from the buying of books, if he has the money that is demanded for them , unless it be to withstand the malice of the seller, or to await a more favourable opportunity of buying…

Bury also had much to say on the care of books.

We are… exercising an office of sacred piety when we treat books carefully, and again when we restore them to their proper places. As to the opening and closing of books, let there be due moderation, that they be not unclasped in precipitate haste, nor when we have finished our inspection be put away without being duly closed.

However, Bury did not always following his own advice. It was recorded that the Bishop’s bedroom was so littered with books that it was hardly possible to stand or move in it without treading upon some volume.

The thoughtless treatment of books by a negligent reader was heartily condemned by Bury.

He distributes a multitude of straws, which he inserts to stick out in different places, so that the halm may remind him of what his memory cannot retain. These straws, because the book has no stomach to digest them, and no one takes them out, first distend the book from its wonted closing, and at length being carelessly abandoned to oblivion, go to decay. He does not fear to eat fruit or cheese over an open book, or carelessly to carry a cup to and from his mouth…Now the rain is over and gone and the flowers have appeared in our land. Then the scholar we are speaking of, a neglector rather than a inspector of books, will stuff his volume with violets and primroses, with roses and quatrefoil…’

Bury has harsh things to say regarding the annotators and mutilators of books.

But he handling of books is specially to be forbidden to those shameless youths, who as soon as they have learned to form the shapes of letters, straightaway, if they have the opportunity, become unhappy commentators, and whenever the find an extra margin about the text, furnish it with monstrous alphabets, or if any other frivolity strikes their fancy, at once their pen begins to write it…Again, there is a class of thieves shamefully mutilating books, who cut away the margins from the sides to use as material for letters, leaving only the text, or employ the leaves from the ends…for various uses and abuses.’

Plus ca change…

[R.M.Healey]